If you ask residents in the Shida area about the Shidahood Association (師大三里里民自救會), you’ll get very different answers. When I asked bunch of old ladies in a neighborhood park, some of them in wheelchairs, they spat back expletives. “They’re wangbadan!” (a term of abuse similar to “bastards”), said one woman, while another called the association “hateful.” Elsewhere, one man asked scornfully, “Why won’t they just let people do business?” These were mainly resident property and business owners, and quite a few of them were elderly.

Much of the crowd at a 10:30pm street-side trash pickup however declared that the Shidahood Association was doing very important things. They claimed to be “highly supportive,” “very much in favor,” or say, “Without them, this neighborhood would be chaos.” These were mostly middle-aged and middle-class residents, working professionals who inhabit the area’s quieter streets and lanes.

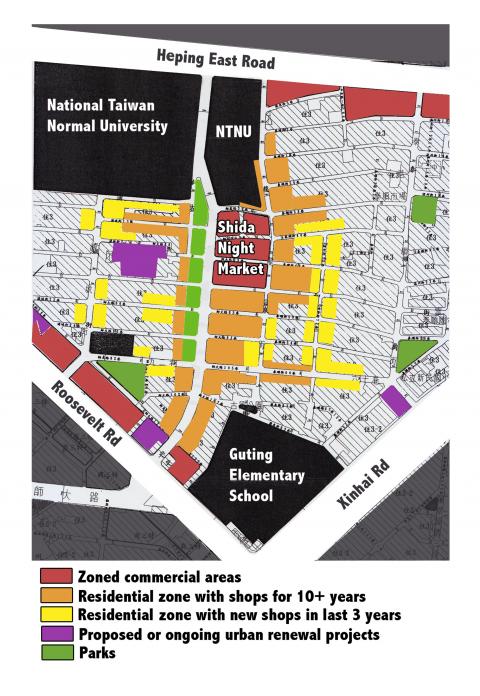

What’s at stake is the future shape of Shida. To many, the neighborhood is Taiwan’s funky university district, a bustling night market zone of indie boutiques and coffee bars that serves tens of thousands of young people, a hip music crowd and a growing number of tourists. Many Shida residents meanwhile want to reclaim their neighborhood, kick out hundreds of businesses and keep the area prim, quiet and residential.

Diagram: David Frazier

The Shidahood Association formed last November with the stated goal of expelling “300 illegal businesses” and “200 legal businesses” of the 700 to 800 businesses estimated to be in Shida, including restaurants, clothing shops and the night market stalls. Association Chairman Jerry Liu (劉振偉) claims the group has between 2,000 and 3,000 active supporters, plus an even larger “silent majority” of the neighborhood’s 16,500 residents.

Due to the combined pressure of Shidahood and Taipei City, more than 100 Shida businesses have shut down in the last three months, and many more have received fines or notices that could cause them to close. Several are longstanding neighborhood landmarks, like the 16-year-old rock club Underworld (地下社會), which helped give birth to Taiwan’s indie rock movement. It shut down on July 15 to avoid government fines.

Roxy Jr. Cafe, a bar-restaurant and favorite expat watering hole open since 1994 was recently fined NT$150,000 for illegal operation and faces more fines or forced closure if it keeps selling alcohol to customers who don’t also buy meals. Other shops say they may close because business is getting worse and they no longer trust the regulatory environment.

Photo: David Frazier

“I’ve been here for 18 years running the exact same business with the same license and have never had a problem, so why am I having a problem now?” asks Roxy owner Ling Wei (凌威).

“I invested NT$15 million in three restaurants here because I trusted the law and I trusted the city. I sold my house in India. Just last year, Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌) was promoting Shida as a commercial district. Now I ask myself, is this Taiwan or is this China?” says Andy Singh, an Indian restaurateur who is fighting the city.

“We residents are the victims,” counters Liu. “The noise and pollution in this neighborhood are ruining the quality of life.”

Photo: David Frazier

“The city has been negligent for too long,” Liu continues. “The city can have its commercial districts, but this is zoned as a residential area, so the city should uphold its own regulations. This should have been done 10 years ago.”

Liu is a retired executive for the Swedish truck manufacturer, Scania. His work has taken him around the world, including the suburbs of Chicago, where he was posted for a number of years, but his family has lived in Shida for decades. He speaks English fluently and has a deep understanding of the law. In conversation, he is charming, though when he speaks of the moral decay of his neighborhood, he sometimes gets angry and begins to quiver.

If nothing else, Liu is a highly efficient organizer and lobbyist. His association’s blog details violations to look for — including kitchen exhaust, excessive stink, pollution, noise, fire code violations and illegal signage — and how to make reports to government agencies. Association members can frequently be seen patrolling the neighborhood with digital cameras. The restaurant 1885 Burger received around 600 complaints about its kitchen exhaust over a six-month period, an average of more than three complaints per day.

Generally, the Shidahood blog has anticipated which streets and lanes will see heavy inspections weeks before they happen and named hit-lists of undesirable businesses. Notably, these have included Toasteria, Rabbit Rabbit (兔子兔子) and 1885 Burger, all of which closed down.

Not long after the Shidahood Association formed, Taipei City formed a Special Shida Taskforce (師大專案小組) headed by deputy mayor Sherman Chen (陳雄文) and involving a wide array of government departments. So far, the city has put a moratorium on the phrase “Shida Night Market” and stopped recommending Shida as a tourist destination (along with Yongkang St., an area loved by foodies that includes Taiwan’s most famous restaurant, Ding Tai Fung.)

Then in April, the city began its first wave of inspections and fines. It first targeted Pucheng Street, Alley 13, otherwise known as “International Food Street” (異國美食街), a lane that had been filled with restaurants for at least 15 years. Now only one restaurant remains, Singh’s Out of India.

Singh believes this first campaign went beyond regulation and into what he calls “gangster tactics.”

“One morning, a group of TV cameras showed up outside my shop. They were led by City Councilor Lee Hsin (李新), who was charging that I had illegally built an exhaust pipe a few days before without my second floor neighbor’s permission. The pipe had been there for six months, but they wanted me to put the exhaust into the alley, so they could complain to the EPA,” said Singh.

“My second floor neighbor did not file the complaint,” he continued. “It was some third party, and we never found out who it was. When we went to the police station later that day to make a challenge, we found the complaint had been cancelled.”

Singh has filed a lawsuit for intimidation against the councilman. His shop, Out of India, has received a NT$60,000 fine for illegal operation.

As in much of Taipei, there is a huge gray area between what is legal and what is enforced. At present, Shida only contains three city blocks that are zoned for commercial use, though food stalls have sprawled over an area three times as large for at least 20 years.

“The problem is that every business in Taipei is illegal. If you strictly enforced the law, maybe you’d have to shut down 3,000 restaurants in Taipei, but they’re only enforcing it in Shida,” says Peng Yang-kae (彭揚凱), secretary general of OURs, an NGO specializing in urban planning.

Shida residents reached a tipping point in the last three years, when the number of businesses jumped from 300 to over 700, according to Peng’s estimate. Traditional noodle shops and food stalls gave way to shops for trendy Korean fashions, and crowds swelled to 30,000 a day or more. The new shops were not “neighborhood stakeholders,” says Liu, but “outsiders.”

At the same time, real estate brokers bought up shop fronts, divided them into small lots, often illegally, and rents began to skyrocket. When one cafe went to renew its lease in 2011, the landlord increased the rent from NT$80,000 a month to NT$250,000. Other landlords began converting residential first-floor lots for commercial use, and the night market began to sprawl well beyond any previously established boundaries.

Liu now says his ideal is for Shida to have around 400 fully legal businesses, and argues no exceptions should be made on account of culture, like the rock club Underworld. “Stripping or pole dancing is also culture, but I don’t want it in my neighborhood,” he said.

For the moment, city inspections and shop closures continue, and foot traffic in Shida has dropped significantly. Businesses speak widely of a scandal involving construction companies and extensive redevelopment, but evidence is circumstantial. More practically, six businesses recently won administrative appeals filed with the Ministry of the Interior, refunding fines or allowing continued operation.

In short, the fight for the neighborhood continues, as does uncertainty over its future.

“The city should take a position and set forth some sort of vision for Shida,” says Peng. “But they haven’t done that so far. They’re just sitting back and watching this happen.”

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike