I experienced a number of Proustian madeleine moments while sitting in front of Jeng Jun-dian’s (鄭君殿) Louise, a painting of a blonde cherubic girl emerging from a body of water. The painting, one of almost two dozen currently on display at Eslite Gallery (誠品畫廊) in Taipei, elicited memories, if only briefly, of the crystal clear lakes I used to swim in during my youth. Another, Casseroles 1 (鍋子 1), a large-scale still life of kitchen pots and pans, made my stomach rumble with thoughts of my mother preparing a Sunday dinner. That’s what Jeng’s paintings do: they evoke in the mind of the viewer the domestic simplicity and innocence of times past.

But they do so while avoiding any nostalgic, suburban sentimentality because Jeng’s technique keeps the viewer’s gaze within a logical contour of line and color, which, depending on your distance from the painting, shifts back and forth from a lyrical realism to an almost geometric abstraction. It’s this formal multiplicity of perspectives that had the curious effect of snapping me back into the present.

It’s been four years since Jeng held his last solo show, and judging by the number of circular red stickers (indicating a sale) in this exhibition, titled Day In, Day Out (日常生活), the show is a resounding success. Perhaps this is due to the hype that Eslite Gallery has become adept at generating. Yet there is a confidence of style and maturity of technique in this show that were not fully realized in Jeng’s previous works.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Jeng’s early landscapes expressed a neo-impressionist sensibility of rich earthy colors that emphasized the play of light off reflective surfaces: think later Edouard Manet, though with a greater use of blacks and grays.

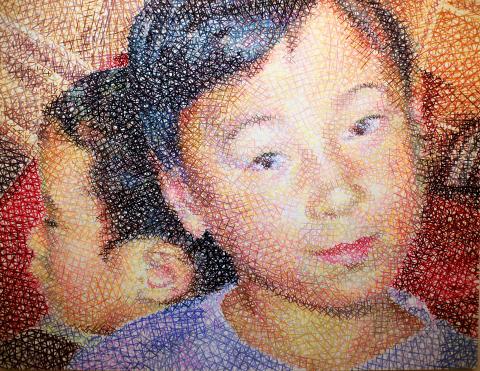

Over the past decade or so, Jeng has scaled back his palette while evolving a cross-hatching style, for which he layers the surface of the canvas with thousands of single, interconnected brush strokes of solid coloring. Blues and yellows largely disappear in favor of chartreuse, forest green and burnt sienna — the latter he emphasizes in his portraits as well.

But those earlier paintings appear too effusive — the discovery of the technique seemingly controlling Jeng, rather than being controlled by him. He was like a child who has discovered the taste of chocolate and proceeds to gorge on everything in the sweetshop. Laurence (2006 to 2008), a portrait of a woman, for example, suffers from this kind of exuberance. There is a distracting muddle of shading around the right side of the subject’s nose that essentially eliminates its outline. The gradations of color around the left cheek make the woman look as though she is wearing the half-face mask from Phantom of the Opera. It just seems slightly unbalanced — which, on second thought, might have been his purpose.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Regardless, with Day In, Day Out, he has gained greater control over shading, while expanding his color scheme in some paintings, and limiting it in others. No brushstroke is wasted; no shadow seems out of place. Indeed, Jeng seems to be using fewer brushstrokes and achieving an even greater effect.

Take Louise for example. Jeng’s use of rich coloring immediately draws us towards the paintings’ surface — an effect muted in the earlier paintings by the use of browns and greens. Up close, we ponder the delicate yellows and blues, tinged here and there with pinks and reds. As we pull back, we come to appreciate the plasticity of painting as it gradually unfolds its harmonious realism.

In others, such as Garcon and On (Sacha), blacks and grays replace color. But even here, a wisp of yellow or a strand of peacock blue allows for a degree of complexity and warmth. Jeng’s subject matter — mostly children on their own turfs or still lifes of kitchen pots and pans — is ideally suited to his technique.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

There are also a few landscape paintings and some sketches on display that hark back to Jeng’s earlier work. But it’s the artist’s works created over the past four years that impress the most.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of