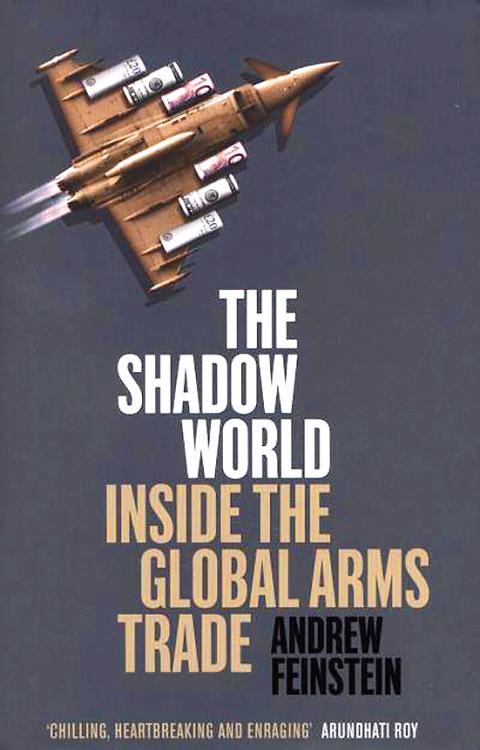

This book, though lively, makes extremely depressing reading. Its subject is the arms trade, as pursued by both private arms traders and governments, with corruption — bribes paid to secure deals for your company or country rather than competing ones — central to its comprehensive narrative.

The author was an African National Congress legislator in the early years of post-apartheid South Africa, but was eventually marginalized following his investigation into aspects of his country’s affairs, eventually detailed in his book After the Party: A Personal and Political Journey Inside the ANC.

Whether you’re reading about the UK’s 1985 Al Yamamah (the dove) sale of arms to Saudi Arabia (the biggest such sale the world had seen), the notorious Iran-Contra scandal (the illegal sale of arms by the White House to Iran to illegally finance opposition to the elected government of Nicaragua that came to light in 1986), arms sales to West Africa that fueled the orgy of rape, murder and mutilation in Sierra Leone in 1999, the collateral casualties caused by the use of drones, the far from straightforward relations of Western governments with post-Shah Iran and Gaddafi’s Libya, or the roles of the UK’s BAE and the US’ Lockheed Martin, The Shadow World is a book it’s only possible to take in very small doses.

So, as respite, I watched the 2005 film Lord of War. Small respite! This movie, with its superb script by the director Andrew Niccol, previewed everything I’d been reading about, but in a vivid, immediate and harrowing manner. The film pulls no punches, and was strongly endorsed by Amnesty International. Though focusing on an independent rogue arms dealer, it shows him being released from US custody on orders from above — too useful to the White House of the day that, he remarks, sold more military merchandize in 24 hours than he did in a year, but which needed his like for recipients it couldn’t be seen as supplying.

At the end, across the screen you read that the world’s biggest arms suppliers are the US, UK, Russia, France and China, and that these are also the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. It could have added that they also all possess nuclear weapons.

But aren’t all guns, tanks, grenades, helicopter gunships and cluster bombs instruments of the devil? Well, I decided, you can either take a root-and-branch pacifist position like this — a position that classical Buddhism or a poet such as William Blake adopts — or you can investigate the trade in this deadly cargo in a scholarly book. The latter is the course taken by Andrew Feinstein whose The Shadow World is said to be the first in-depth look at the international arms trade in more than 25 years.

One thing the book is at pains to emphasize is that government and private trading in arms are interrelated. Presidents and prime ministers enthusiastically act as salesmen for their countries’ armaments and, if challenged on these often semi-secretive missions, retort in terms of their nations’ economies and job creation. It would be easy to reply that you have no wish to participate in a prosperity based on the certain deaths of people in places such as Liberia, Darfur or Afghanistan, or that to eat your breakfast, kiss your wife and children good-bye, and then go to work manufacturing devices specifically designed to blow people’s feet off — something many workers must do on a daily basis — is inconceivable as the basis for any responsible life. Feinstein, however, opts to control his anger and dedicate himself instead to research that is likely to form the first port of call for enquirers into his dark subject for decades to come.

I’ve recently tried an Internet search to find developed countries that survive without an arms industry. It’s been a depressing occupation because to date I haven’t found one. This, though, is no reason why individuals shouldn’t take up a non-violent position.

Do arms deals cause wars? To a serious degree, yes, if only because peace is an unprofitable time for the international arms trade. And its work certainly makes the eventual death and mutilation in wars far worse. In addition, the existence of arms stockpiles exerts a pressure for their use.

To return to the US, Feinstein considers US President Barack Obama’s declared program of changing the way Americans do politics. He sees little change on the arms front up to the middle of last year, citing the announcement in October 2010 that the US would sell armaments, including cluster bombs, to Saudi Arabia, an undemocratic and arguably repressive state, worth US$60 billion over a 15 to 20 year period. Officially the largest arms deal ever signed by the US with a foreign country, this was left unmentioned when Obama declared his country’s solidarity with participants in the Arab Spring, Feinstein notes.

He also states that the Pentagon’s books haven’t been audited for more than 20 years. It has recently expressed the hope that it will be “audit-ready” by 2017, a claim that a bipartisan group of senators considered “unlikely.”

Feinstein concludes by asking what can be done to improve matters. The US must lead the way, he says. Political contributions by arms manufacturers should be prohibited, and the “legal bribery” (Feinstein’s phrase) associated with arms trading stopped. The UN’s provisional Arms Trade Treaty, a multilateral code of conduct, is scheduled to be signed this year, and should be, he says.

Further details on all these matters can be found by going to www.theshadowworld.com; see also the relevant section of Amnesty International’s Web site (www.amnesty.org), or the UK-oriented Campaign Against the Arms Trade (www.caat.org.uk). And note that this book, indispensable as it is, excludes from its brief any consideration of non-conventional weapons.

Finally, if reading this hefty but brilliantly researched work seems a daunting prospect, then at least watch Lord of War, or watch it again. A full-length documentary of The Shadow World itself is currently in the planning stage.

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates