If the 1970s are remembered fondly at all, it’s through the prism of stack heels, feathers, glitter and flares, yet on BBC TV you can have your memories of the glam rock era destroyed in half an hour by watching old episodes of Top of the Pops. It’s clear that Cliff Richard and the Wurzels spent more time in the charts than Roxy Music or T Rex, forming an incongruously bland soundtrack to years of political and industrial upheaval.

“The decade of David Bowie,” writes Peter Doggett of his latest subject, was fired not “by idealism or optimism, but by dread and misgiving.” The latter sentiments, along with bitterness and blame, comprise “the dominant folk memory” of the 1970s, the 1960s having ended sourly for those who had believed in the promise of social transformation.

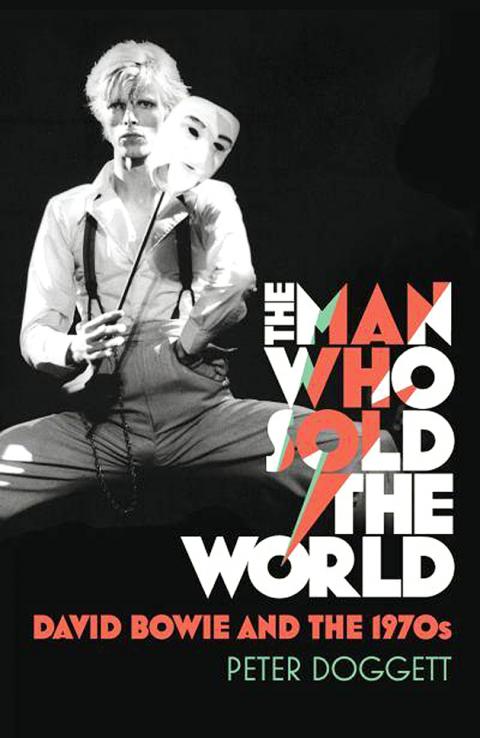

Doggett’s previous book, You Never Give Me Your Money, was an account of how the Beatles, having preached spiritual investment and material divestment in the previous decade, spent years after their split in 1970 dragging each other through courts and accountants’ offices. In The Man Who Sold the World he retrieves this thread of disillusionment and applies it to Bowie’s “long Seventies,” which begins with his first hit, Space Oddity (1969), and ends with Scary Monsters (1980), for most fans his last truly satisfying album.

David Bowie remains a cult artist (though a hugely popular one) in a way the Beatles never were. There’s an extent to which you already have to be a pop music fan in order to be a Bowie fan, and his appeal in the 1970s did not extend across the generations. But his music and image-making are strikingly important to the notion of the British propensity for intense, unusual creativity in pop culture. Bowie’s originality is a source of pride, though Doggett’s detailed study reveals it to be more a genius for stealing the right bits from his rivals. He created Ziggy Stardust partly from how he perceived Marc Bolan to be at the height of his fame: spectral, imperious, out of control.

The book’s song-by-song format takes after Revolution in the Head, Ian MacDonald’s superb 1994 study of the Beatles. Doggett writes that MacDonald was under contract to write a similar analysis of Bowie’s work at the time of his death in 2003; he was asked by MacDonald’s editor to revive the project, which he does admirably.

His sharpest insights come in the discussion of what he clearly feels are the most important songs. Hunky Dory’s Oh! You Pretty Things, with its creepy exhortation to “make way for the Homo Superior,” is only in part a hymn to Nietzsche. It was also a way for Bowie, in his own words, to write his “own problems out”: the “crack in the sky” he witnesses in the first verse was reported by his half-brother, Terry Burns, incarcerated in a south London asylum for nearly 20 years before he killed himself in 1985. “According to Jung,” Bowie once observed with rare understatement, “to see cracks in the sky is not really quite on.”

Doggett discusses Bowie’s cocaine use, which left him “ravaged beyond belief” on his 1974 American tour, and his repeated references in interviews to the coming of a Hitler-like leader. It turns out that even in the 1960s he was harping on about this, which suggests that his notorious mid-1970s comments on the desirability of British fascism sprang as much from a genuine conviction that society was fragmenting as from his drug addiction.

The songs on the 1974 album Diamond Dogs, which loosely trace the story arc of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, give weight to this idea. The songs We Are the Dead and 1984 were sketched out after Bowie took the Trans-Siberian Express across “the fabled communist paradise” of Russia. He told his wife, Angie, that he had “never been so damned scared in my life.” Listening to the song’s paranoid chorus — “Beware the savage jaw of 1984” — Doggett conjures “the image of a rabid slobbering hound.”

He identifies the album’s “nexus between science fiction, catastrophe and consumerism” as having been a preoccupation of the 1950s, carried into the 1970s by writers such as JG Ballard and Colin Wilson, whose 1971 history of the occult was read and absorbed, perhaps a bit too comprehensively, by the autodidact rock star. Bowie said in a later interview about the 1970s that “nobody knew who they were” once the 1960s were over: to him, the National Front, union membership, neoliberal thought, or punk rock, whether illusive or transformative, were rudders for the rudderless — all Big Brothers of a kind.

In his book In the Seventies, the biographer and memoirist Barry Miles has broadly the same take on the decade as Doggett, but his account’s blithe style and the notable absence of political figures or movements beyond the transatlantic underground hint that he was part of that turn inwards, away from collective action towards self-creation.

In the Seventies returns to themes and subjects familiar to readers of Miles’s 2002 book In the Sixties, notably his recording and archiving work with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, which took him to upstate New York, where he was an enthusiastic participant in Ginsberg’s commune for city-frazzled poets, before returning to the countercultural bubbles of downtown Manhattan and Berkeley, California.

The son of domestic servants, he lightly skewers the pretensions of the privileged, yet angry, drop-outs he encounters. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, “self-appointed youth leaders” who sabotage a Greenwich Village benefit in 1970 for the imprisoned psychologist Timothy Leary, possess “two enormous egos” which “buffeted around the room like weather balloons.”

He eventually moves to the Chelsea Hotel, where he had stayed at the end of the 1960s, and then back to London, where he writes for the New Musical Express, wolfing smoked salmon and champagne at press junkets and being flown to New York on Concorde for the sole purpose of reviewing a Tangerine Dream concert. All this is related in a way that suggests such experiences are, if not normal, then accessible to anyone who is able to cast off the shackles of class and societal expectation, regardless of the times they live in. Miles told the Guardian last year that his mother used to scold him for his aspirations, saying: “You’re flying too high, my boy.” Unlike Bowie, who described “hitting an all-time low” in Ashes to Ashes, his contrite reckoning of a strung-out decade, the less noteworthy Miles never did come crashing down.

Publication Notes

The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s

By Peter Doggett

424 pages

Bodley Head

Hardcover: UK

In the Seventies: Adventures in the Counterculture

By Barry Miles

264 pages

Serpent’s Tail

Softcover: UK

Earlier this month, a Hong Kong ship, Shunxin-39, was identified as the ship that had cut telecom cables on the seabed north of Keelung. The ship, owned out of Hong Kong and variously described as registered in Cameroon (as Shunxin-39) and Tanzania (as Xinshun-39), was originally People’s Republic of China (PRC)-flagged, but changed registries in 2024, according to Maritime Executive magazine. The Financial Times published tracking data for the ship showing it crossing a number of undersea cables off northern Taiwan over the course of several days. The intent was clear. Shunxin-39, which according to the Taiwan Coast Guard was crewed

China’s military launched a record number of warplane incursions around Taiwan last year as it builds its ability to launch full-scale invasion, something a former chief of Taiwan’s armed forces said Beijing could be capable of within a decade. Analysts said China’s relentless harassment had taken a toll on Taiwan’s resources, but had failed to convince them to capitulate, largely because the threat of invasion was still an empty one, for now. Xi Jinping’s (習近平) determination to annex Taiwan under what the president terms “reunification” is no secret. He has publicly and stridently promised to bring it under Communist party (CCP) control,

On Sept. 27 last year, three climate activists were arrested for throwing soup over Sunflowers by Vincent van Gogh at London’s National Gallery. The Just Stop Oil protest landed on international front pages. But will the action help further the activists’ cause to end fossil fuels? Scientists are beginning to find answers to this question. The number of protests more than tripled between 2006 and 2020 and researchers are working out which tactics are most likely to change public opinion, influence voting behavior, change policy or even overthrow political regimes. “We are experiencing the largest wave of protests in documented history,” says

In Taiwan’s politics the party chair is an extremely influential position. Typically this person is the presumed presidential candidate or serving president. In the last presidential election, two of the three candidates were also leaders of their party. Only one party chair race had been planned for this year, but with the Jan. 1 resignation by the currently indicted Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) two parties are now in play. If a challenger to acting Chairman Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) appears we will examine that race in more depth. Currently their election is set for Feb. 15. EXTREMELY