Columbia University Press’ admirable series Modern Chinese Literature from Taiwan has seen English versions of many fine books see the light of day. The Old Capital by Chu Tien-hsin (朱天心), My South Seas Sleeping Beauty (Chang Kwei-hsing, 張貴興), Orphan of Asia (Wu Cho-liu, 吳濁流), Wintry Night (Lee Chiao, 李喬), City of the Queen (Shih Shu-ching, 施叔青), Three-Legged Horse (Cheng Ching-wen, 鄭清文) and Notes of a Desolate Man (Chu Tien-wen, 朱天文) — each of these helped draw the world’s attention to modern Taiwanese prose fiction as well as giving resident foreigners who don’t read Chinese a taste of the best that was being produced under their very noses. All these books were reviewed in the Taipei Times over the last decade.

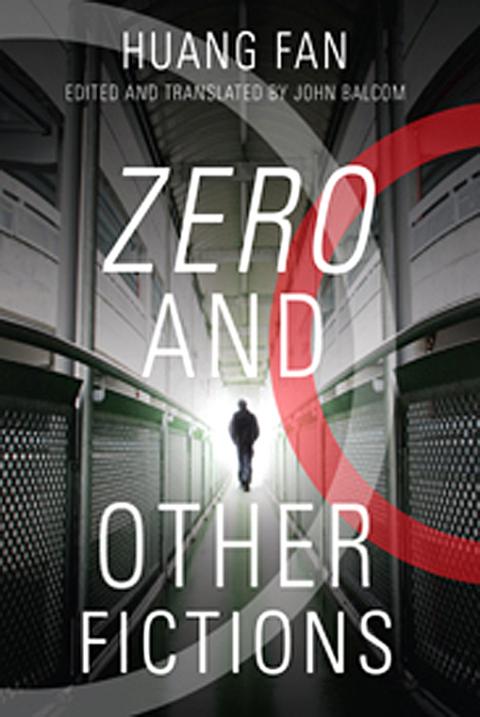

Now comes Zero and Other Fictions by Huang Fan (黃凡). It consists of four items: a novella (Zero) and three shorter pieces. In his preface the editor and main translator, John Balcom, makes high claims for Huang’s stature among modern Taiwanese literary practitioners. If this is indeed the case, it’s strange that this collection is appearing only now. Zero, for example, dates from 1981, whereas the short story Lai Suo, which Balcom claims has attained the status of a modern classic, is even older, appearing first in 1979.

Zero is set in the future and describes the miserable fate of one Xi De, an independent thinker in a totalitarian society. He works in a responsible position in the society’s administrative center but harbors doubts that are quickly detected by the authorities. He’s transferred to a less important city where he makes contact with a shadowy resistance group called the Defend the Earth Army. He’s quickly betrayed, however, and finds himself back facing a Big Brother with, as the story ends, the inevitable consequences.

By Huang Fan

Echoes of earlier dystopian novels are inevitable, with Xi De a new incarnation of Winston Smith in Orwell’s 1984 and Bernard Marx in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, to name only his most obvious precursors. Looking slightly further afield, Huang having “excess populations” of “inferior races” quietly exterminated in his imagined future brings to mind Max Nordau’s Degeneration of 1895, and more specifically Sven Lindqvist’s unforgettable “Exterminate All the Brutes,” which pointed to exactly the same European attitudes toward under-developed cultures at the time Conrad was writing his Heart of Darkness.

The problem with Zero is that it doesn’t appear to add very much to earlier fictional visions of an engineered, eugenic future. Maybe it reads more persuasively in Chinese, but this seems unlikely as Balcom is one of the best translators from Chinese into English. The scientific control of human reproduction so that sexual fertility becomes an irrelevance is at the heart of Brave New World, for example. Sexual orgies as a reward for obedient behavior feature there as well, and a drug that rewards with peaceful oblivion (a “green liquor” here, “soma” in Huxley) is also common to the two books.

As for Orwell, the face of the ruling tyrant permanently on a TV screen is central to 1984, and an old lag singing a rough song lamenting the modern era is found both here and in Orwell’s book. To give Huang credit, he does tacitly acknowledge the link by giving the character who pens a book blowing the gaff on the ruling party (Xi De finds it at the bottom of a well) the name Winston.

What is original, apart from some social details, is the idea of a device called Nanning that is able to explode nuclear bombs anywhere on earth, and so gives the ruling party its near-complete control. There’s also a science fiction element (the ruling party as beings from outer space) that, however, appears to be debunked at the end of the tale as a fabrication fed to the Defend the Earth Army by the party.

I found Zero mildly engaging to read but in the end unsatisfactory. The other three items in the book were even less alluring. I was both baffled and annoyed by Lai Suo. It’s a surreal story set in Taiwan, with the Japanese seemingly still in charge even in the 1970s, but with so many time shifts that you can’t really be sure. The Intelligent Man (translated by Yingtsih Balcom) briskly tells the story of a Taiwanese man who acquires three wives after engaging in business in Taipei, New York and China, and as the tale closes is about to acquire a fourth in Hong Kong. I couldn’t see the point of it.

Lastly, How to Measure the Width of a Ditch is an extended exercise in facetiousness. It might be claimed by some to subvert the whole idea of fiction by deliberately confusing ideas of truth and memory, the imagined and the real. But to me it seemed merely facetious. I promised myself a cup of coffee when I reached the end of its 15 pages, but by the end I was so relieved that I forgot about the coffee.

It’s unusual to have to review a book that seems to have so few qualities. The praise the translator and editor gives the author makes me doubt my objectivity, but as far as I can see I’m in full possession of my faculties. I can’t, therefore, recommend Zero and Other Fictions, though I hope Columbia will continue its efforts to give modern Taiwanese novelists an English-reading audience. But as for Huang’s world, it feels essentially critical and satiric, and at worst sardonic and morose. Perhaps I’m an inveterate romantic, but after reading this book I felt like walking on some sea-cliffs, looking at the ocean, and feeling the wind in my hair.

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she