To describe a documentary about Taiwan’s democracy movement as an epic love story may seem odd, but that’s what Hand in Hand (牽阮的手) feels like. The latest work by director couple Yen Lan-chuan (顏蘭權) and Juang Yi-tzeng (莊益增) threads together interviews, found footage, animation, archival records and manuscripts to tell of the six-decade relationship between democracy activists Tien Meng-shu (田孟淑) and Tien Chao-ming (田朝明). The couple’s undying love alone, however, is not enough to make the film epic. What transcends the romance is the director’s ambition to join the personal and the political, bringing the country’s past to life through the stories of individuals who lived trough it.

The film begins in 1950s Tainan. A 17-year-old high school girl, Tien Meng-shu, falls in love with Japanese-educated physician Tien Chao-ming, who is 16 years her senior. The young woman’s wealthy, reputable family does not approve of the town doctor, so she elopes with her lover and never returns home. Little did the fearless young lady know that their lives over the next 60 years would closely follow the thread of Taiwan’s post-World War II political history.

The progression focuses on Tien Meng-shu, who grows from an innocent schoolgirl to a devoted advocate of human rights and democracy better known as Mama Tien (田媽媽) among political activists and dissidents. The directors rely heavily on Mama Tien’s memory to conjure up the past, but instead of using archives and talking heads, they ingeniously use animation to bring the story to life. Through the animated sequences, we come to know doctor Tien’s friendship with Taiwanese intellectual and political critic Lee Wan-chu (李萬居) and Chinese scholar and democracy pioneer Lei Chen (雷震), who co-founded Free China (自由中國), a publication that advocated liberalism and was sharply critical of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). The couple become intensely involved in the dangwai (黨外, outside the party) movement, and their clinic becomes a place where political dissidents such as a young Chen Chu (陳菊) — now mayor of Greater Kaohsiung — hold meetings with members of Amnesty International in an attempt to rescue political prisoners and victims of the White Terror.

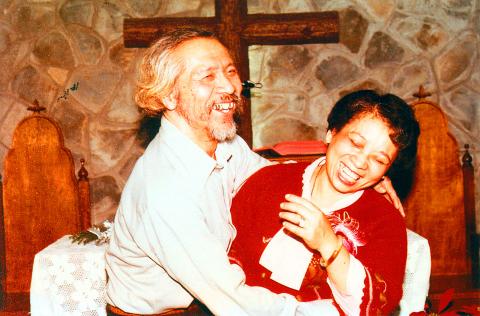

Photo courtesy of Juang Yi-tzeng and Yen Lan-chuan

One of the film’s heartbreaking moments is an animated sequence depicting Yeh Chu-lan (葉菊蘭), the wife of human rights activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕), as she decides not to stop her husband from setting himself aflame in protest against the lack of freedom of speech under the authoritarian rule of the KMT in 1989. Another sequence shows the Tiens’ oldest daughter, Democratic Progressive Party Legislator Tien Chiu-chin (田秋堇), going to Lin I-hsiung’s (林義雄) home on Feb. 28, 1980, and discovering the appalling murders of Lin’s 60-year-old mother and seven-year-old twin daughters while he was detained on charges of insurrection.

Completed after four years of arduous work by the makers of Let It Be (無米樂, 2005), Hand in Hand brings to light political events such as the 228 Incident, the Formosa Incident and the lifting of martial law not as hollow dates in history books but as parts of people’s lives, showing the passion, strength and sacrifice that helped to shape Taiwanese society.

The film owes much of its power to its protagonists, who are ready to die for their ideals and beliefs. Through this lens, the Tiens’ love for the land remains untainted and incorrupt, and so is the love between the couple as the aged Mama Tien is seen caressing the bedridden Tien Chao-ming, who lost his ability to move and communicate after a stroke in 2004 and passed away last year at the age of 93.

Photo courtesy of Juang Yi-tzeng and Yen Lan-chuan

In the middle of the film, director Juang acts as an off-screen narrator pondering a young blogger’s remark: “How does the 228 Incident have anything to do with me?” The question is answered in Hand in Hand, a must-see for anyone interested in the history of Taiwan’s democracy movement, and even more important for those who don’t think it affects them.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name