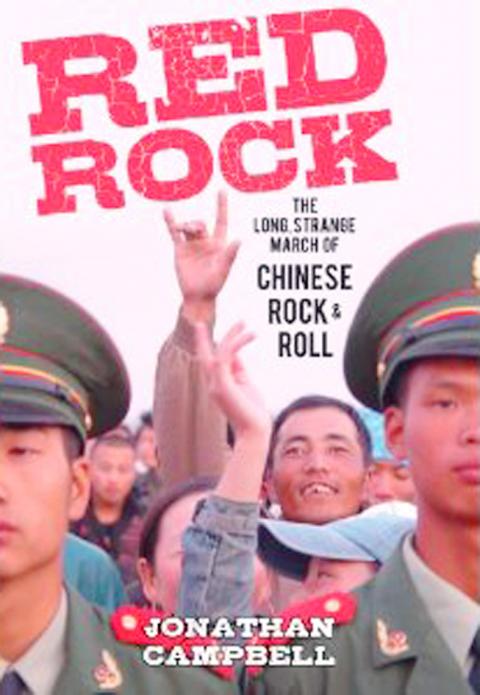

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the birth of rock ’n’ roll in China, and on Saturday, China’s national day, Hong Kong’s Earnshaw Books will release the first English-language history of Chinese rock to see publication in more than a decade, Red Rock: The Long Strange March of Chinese Rock & Roll. Author Jonathan Campbell, a journalist, musician and rock promoter living in Beijing since 2005, pays an obsequious homage to a Beijing-centric scene of loud, distorted guitars and its awesomely paradoxical existence — first it had to exist in spite of China’s authoritarian government, and more recently it’s found a way to be rebellious and nationalistic at once.

It’s a tantalizing history for any music fan in Asia, and one wishes Campbell had done it better justice. His book does give a record of most of the key musicians, bands, concerts and incidents in the young history of Chinese rock, but it too often reads like a fan’s tribute to the bands he hangs out with, not like the work of an author on the trail of a significant social history.

How can Chinese rockers be simultaneously rebellious and apolitical? What does rock mean to Chinese kids on an individual level? Where do you draw the line between derivative and original? How does Chinese rock relate to what’s happening in the rest of the world?

There are any number of ways to explore this history, and while Campbell delivers many solid nuggets of information and some interesting insights, this is neither an insider’s tell-all nor an iron-clad history. In the end, one is left wanting for an overall scheme.

The writing itself stems from a series of faithful interviews with important figures, ranging from China’s “godfather of rock” Cui Jian (崔健) to numerous other musicians, music critics and concert organizers. The research painting the backstory, however, is almost completely unaccredited, which is a pity, as this history hasn’t been properly surveyed since Nimrod Baranovitch’s 1997 China’s New Voices, a book that seems to be a major and perhaps under-acknowledged source.

For the most part, Campbell views China’s rock history against the measuring stick of an idealized vision of 1970s punk rock. By this definition, “rock” means down and out, totally unprepared, not giving a damn and dangerous. China’s enormous social inequalities have proved to be fertile ground for this kind of musician, and according to this view, that combined with the growth of a self-aware middle class (which produces these kids) and an authoritarian government suppressing criticism on all levels (which gives them something to rebel against) make China one of the most punk rock places on earth. And admittedly, China’s punk scene continues to be riotously fun, even as punk scenes in the West are weird, cliquey anachronisms.

But the book’s punk measuring stick is applied universally, which means it’s also used to flog many influential, non-punk musicians, like the Taiwanese and Cantonese pop singers of the 1970s and 1980s who were hugely influential in China, as their smuggled-in love ballads offered the first real alternative to Communist Party propaganda music after the Cultural Revolution. Or the British pop group Wham!, which became the first major Western group to perform in China in 1985.

Whether the PRC’s first imported pop songs sucked or not, they paved the way for Cui, China’s first rock ’n’ roll singer. According to nearly every history in either Chinese or English, Cui’s May 9, 1986, nationally televised performance of the song Nothing to My Name (一無所有) marked the birth of Chinese rock.

Beyond the fact that the performance was seen nationwide, the song was played by a band and the musician who wrote it, not sung karaoke style. Next, Cui dressed in average street clothes and looked nothing like the many other pop stars on stage. And finally, the lyrics struck a chord with a generation. They were about a young man who could not win a girl’s love, because he had “nothing to his name”; three years later the student protestors of Tiananmen Square adopted the tune as one of their anthems.

Following Cui’s landmark performance, one Chinese official condemned the song as “a slander directed at our socialist homeland.” But the keyboardist for that gig, Liang Heping (梁和平), saw the beginnings of real social change. “Before Cui Jian, we had no concept of ‘me,’ ‘self,’ or ‘individuality,’” he said.

Rock music, in other words, helped usher in a modern sense of identity for the Chinese youth in the late 1980s, and this included a rather amorphous sense that one had the right to live freely.

In the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, one would expect a government crackdown on rock music. While Cui did have a 1990 concert tour canceled and was prevented from playing large concerts in Beijing for almost 15 years (though he was allowed to play elsewhere in China and internationally), Campbell makes the interesting proposition that rock’s development was actually helped by the June 4, 1989, crackdown. Tiananmen Square, he asserts, was the moment when “the Party decided to pull back in its vision of governing every element of every citizen’s life.”

It is an argument that should be taken seriously. The enormous social transformations that began in the 1990s — including the birth of Chinese punk rock — show us that despite China’s jailing of democracy activists and other dissidents, other more subtly operating wheels of change had been set in motion. Music has become one of many agents of change that have allowed the Chinese to wiggle through and around the blockades of government repression and toward some better reality.

To its credit, Red Rock has collected many key moments of this music’s history. One doubts, however, that it will be the last word in “the long, strange march of Chinese rock ’n’ roll.”

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates