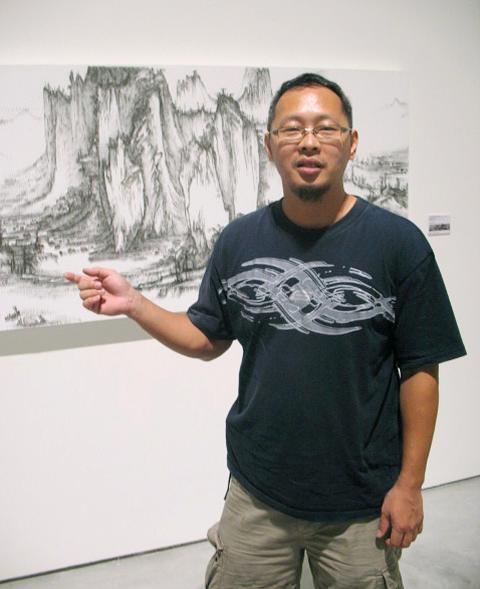

A year and a half ago artist Chen Chun-hao (陳浚豪), 39, began what he jokingly called his “secret project.”

For a decade he’d been creating sculptures, wall pieces and installations using the same medium: thumbtacks. At a 2001 Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) solo exhibition he’d covered an 8m-by-4m portion of a gallery floor with 340,000 tacks laid in the same direction so that they shimmered and waned as you walked around them. Since then he’s used tacks to make everything from billboard-sized works on the sides of buildings to prickly little dolls that you wouldn’t want anywhere near a child.

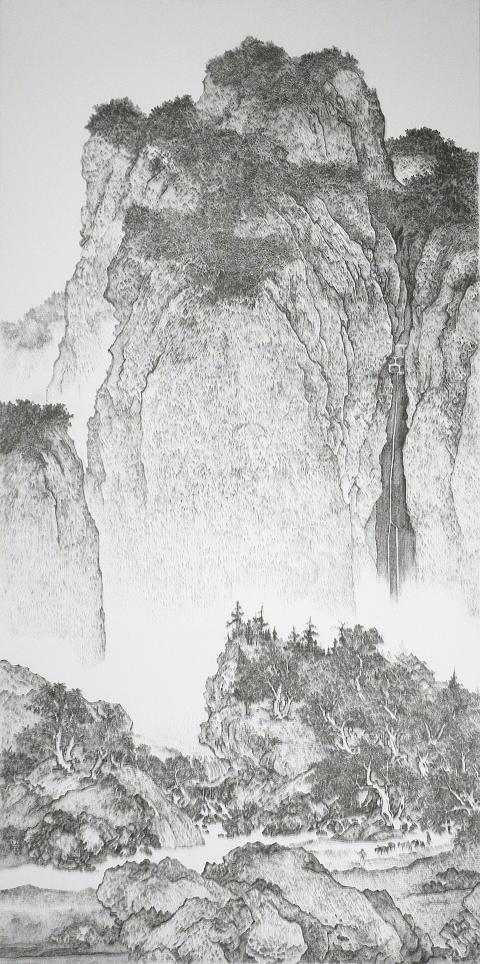

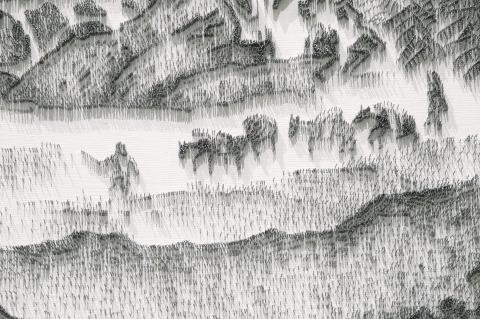

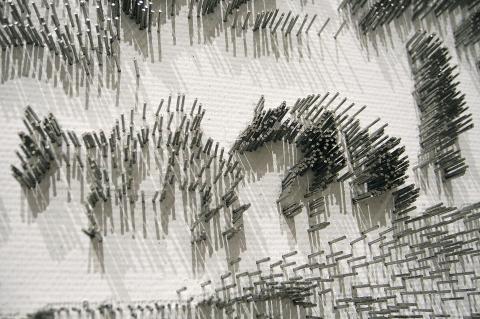

His grand departure from thumbtacks involves another material not usually introduced in art school: “mosquito nails” — little headless pins about a third the size of a toothpick. Chen uses a nail gun to fire them one by one into white canvases stretched over wood, creating reproductions of traditional Chinese ink paintings that often contain tens of thousands of nails in a single piece.

Photo: Taijing Wu, Taipei Times

Seven new “paintings” and a handful of older pieces are on display at Tina Keng Gallery (耿畫廊) in Taipei’s Neihu District (內湖) through Aug. 28. Just looking at them makes you want to slip on a carpal-tunnel-syndrome wrist brace.

Chen’s thumbtack works seem obsessive enough, but for the most part he has assistants helping him with those. A team of 15 worked around the clock for seven days to install his TFAM exhibition 10 years ago, and he hires Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA, 國立臺北藝術大學) students to laboriously set, glue and varnish the tacks in his wall pieces.

For his latest series, he has been spending 10 hours a day alone in his Guandu (關渡) studio, pumping out nails with a loud “phsst-thwack!” Since January last year, Chen says that he has gone through about 5 million nails, laid waste to more than 25 nail guns, and broken two air compressors.

Photo: TaijinG Wu, Taipei Times

“Maybe I should have changed the oil in the first one,” he says. “I took the second one back to the shop and even they weren’t sure [how to deal with a compressor being used in this fashion].”

‘FATE’

Photo: TaijinG Wu, Taipei Times

Chen describes the change from thumbtacks to “mosquito nails” as “fate” (機緣). He started using tacks while studying for a master’s degree at Tainan National University of the Arts (國立臺南藝術大學) in 1998. Back then installation was the thing to do.

“Art became free,” Chen says. “You could do it anywhere with anything. You’d find a space and that was your gallery.”

Photo: TaijinG Wu, Taipei Times

After graduating he found himself working more on the exhibition side of the art world than the creative side. He spent almost a year at the then-foundling Museum of Contemporary Arts, Taipei, three years at Taipei Artists Village when it opened, and six years at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts on the TNUA campus.

While working at that museum, he changed the way exhibitions were financed. Instead of hiring a team of workers to mount exhibitions, he convinced the museum to buy its own table saw and other tools, including a variety of nail guns. Chen, student volunteers and other staff members set up the shows on their own.

“Otherwise we didn’t have the budget for regular exhibitions,” he says. “And this is important for me … I had a chance to explore the tools there. Without that I wouldn’t have found this tool [the ‘mosquito nail’ gun].”

Photo: Blake Carter, Taipei Times

It wasn’t until a 2007 show at VT Art Salon (非常廟藝文空間) — of which Chen was one of the founders — that he started to make money selling his art.

When asked to participate in the Chinese Character Cultural Festival (漢字藝術節) two years ago, he first thought he’d make a wall piece using thumbtacks.

“But then I thought, ‘I’ve already done this type of thing, I’ll try something different.’”

Like many young Taiwanese interested in art, Chen had studied traditional Chinese calligraphy and landscape painting while a student. In 2008 he began an old-fashioned, modern-day apprenticeship with “semi-cursive-style” calligrapher Chang Kuang-bin (張光賓). Chen started experimenting with tools from the museum and ended up using the nail gun to write calligraphy. The series he created for the Chinese Character Cultural Festival is on display at Tina Keng, but the 60cm-by-60cm canvases are dwarfed by the “paintings” that followed, the largest of which is 1.7m wide and 3.45m tall.

DRAWING ON TRADITION

Riffing on Chinese calligraphy and traditional landscapes — called “mountain water” (山水) paintings — isn’t anything terribly new.

From the Cursive productions of Lin Hwai-min’s (林懷民) Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) to the colorful new abstract paintings of Huang Chih-yang (黃致陽), Taiwanese artists have long drawn on the country’s reputation as the preserver of Chinese culture.

Chen’s take on this shows a healthy appreciation for an art form that isn’t just the domain of retirees or the bane of young people forced to spend hours practicing how to properly cradle a brush or worm its goat-hair tip around the start of a stroke. He adjusts the density, the firing depth, and the size of the nails depending on the artist and painting he’s “imitating.”

For 2010 Imitating “Early Spring” by Kuo Hsi in Sung Dynasty 1072 (2010 臨摹北宋郭熙早春圖 1072), he used a longer, 2.1cm nail because he wanted the shadow that the pins cast to help simulate the subtle shading of the original.

His most labor-intensive piece to date, 2011 Imitating “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams” by Fan Kuan in Sung Dynasty 1031 (2011 臨摹北宋范寬谿山行旅圖 1031), is composed of about 750,000 1.8cm nails that he spent three-and-a-half months driving deeper into the canvas for more contrast between the nails and the white background.

“When I started this, the nail gun was just a nail gun,” Chen says, “and now it’s turned into a brush.”

To be honest, I’m a little skeptical as to whether he can keep driving hundreds of thousands of nails into these works without wearing himself out. He’s not.

“I’m only ‘practicing my kung fu (練功期),’” he says with a smile.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has