Masterfully executed, action-packed and with the winning pairing of Donnie Yen (甄子丹) and Takeshi Kaneshiro (金城武), Peter Chan Ho-sun’s (陳可辛) Wu Xia (武俠) promises exhilarating entertainment as a summer blockbuster. But this is not your usual kung fu flick full of fancy wirework or Chinese martial artists drubbing foreigners.

Chan gives the overworked genre a contemporary feel by wedding it with a detective story, continuing his study on the human condition, and in this case, on the theme of revenge and redemption.

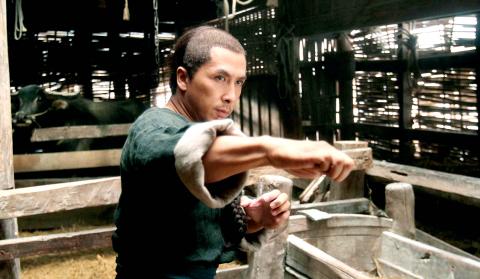

Yen plays Liu Jinxi, a papermaker who lives a peaceful life with his wife, Ayu (Tang Wei, 湯唯), and their two boys in an idyllic village in China’s Yunnan Province. The tranquility is disrupted, however, when Liu accidentally dispatches two vicious thugs who try to rob a general store.

Photo Courtesy of Applause Entertainment

The seemingly gentle papermaker claims he only got lucky, but detective Xu Baijiu (Kaneshiro) is not convinced. After a series of investigations that involve using his forensics skills and expertise on martial arts to reconstruct the deadly fight, Xu comes to believe that Liu is a professional killer and a runaway member of the 72 Demons, a dwindling clan of Tanguts that was persecuted by the Han Chinese and became murderous and vengeful under the leadership of its fierce chief, played by kung fu legend Jimmy Wang Yu (王羽).

It does not take long before Xu’s persistent pursuit unintentionally exposes Liu’s whereabouts to his clansmen. As a result, the renegade murderer is forced to come face-to-face with his shadowy past, which threatens to shatter his second life as a reformed man.

Paying homage to Chang Cheh’s (張徹) classic One Armed Swordsman (獨臂刀) series that propelled Wang to superstardom in the 1960s, Chan’s martial arts flick recalls the sinewy, visceral and boldly violent works exemplary of the golden age of Hong Kong kung fu cinema. To the credit of action star and choreographer Yen, the film’s three climactic fight sequences forsake visual stunts for close-range combat executed in a graphic, ferocious style. The cinematic tradition is further reinforced by the appearances of veteran Kara Hui (惠英紅) and the legendary Wang, who possess both martial arts prowess and commanding on-screen presence.

Photo Courtesy of Applause Entertainment

Thankfully, director Chan does not stop here. He tries to modernize the genre and succeeds. The film will appeal to a contemporary and international audience as it unfolds like a thriller in which Kaneshiro’s erudite character resorts to science when peeling away the layers of mystery surrounding Liu and his kung fu. In Aubrey Lam’s (林愛華) amusingly imaginative script, Chinese martial arts skills are just that — skills, not some magical power. They are the result of physics, physiology and Eastern medicine and thus can be clearly illustrated through the film’s abundant computer-generated charts of human anatomy explaining things like how and why a single blow to a pressure point can kill a man.

As in Chan’s past genre hits such as The Warlords (投名狀), humanity and emotion are never sacrificed for style and form. Wu Xia examines the moral struggles of a killer and a detective who are oftentimes isolated in darkness or framed against the lush Yunnan countryside by the color-saturated cinematography of Jake Pollock and Lai Yiu-fai (黎耀輝).

The characters’ scarred pasts, secrets and fears are revealed, which in turn shape their views, behaviors and beliefs. For example, the film’s opening scene not only affectingly portrays the everyday life of a simple family, but effectively reveals that happiness is cherished and deemed transient by the husband and wife, who separately carry their own burdens from the past.

The most complicated and intriguing character is Xu, for whom emotions can be controlled by acupuncture needles, and human compassion and repentance should never eclipse the law. Like Liu, the detective and off-screen narrator has to battle inner demons as the investigation gradually becomes his personal quest for redemption.

Yen once again proves that an action hero can also pluck heartstrings. But the star of the film is Kaneshiro, who shines with his comic, slightly absurd rendition of the eccentric detective. And though women rarely take central stage in the male-dominated genre, Tang is worth a mention for her convincing portrait of a simple countrywoman whose life revolves around her man and children.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has