Hiring young women to strip at a funeral ceremony might strike some as scandalous, but for many in Taiwan it is an important part of the grieving process.

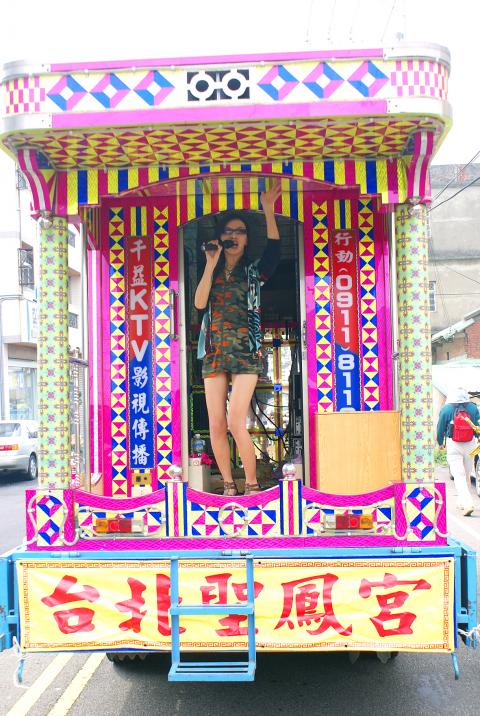

The practice sees scantily clad women on “electric flower cars” (電子花車, diesel trucks refashioned with a stage and special lighting), erotically gyrating to pop songs as a means of sending off the recently deceased — presumably with a smile.

Marc L. Moskowitz, an associate professor at the Department of Anthropology of the University of South Carolina and an expert on Taiwan’s folk religion and popular culture, has just released Dancing for the Dead: Funeral Strippers in Taiwan, a 40-minute documentary about the practice based on hundreds of hours of fieldwork he conducted throughout Taiwan in 2008. (Trailers can be viewed at: people.cas.sc.edu/moskowitz/dancingforthedead.htm.)

Photo courtesy of Marc L. Moskowitz

The interview-driven film — interspersed with stripping performances, pilgrimages and other common religious practices — reveals many of the dichotomies in contemporary Taiwan: rural tradition versus urban modernity; mainstream pop culture versus marginal folk culture; global capitalism versus local identity; and the thin and shifting line between legal and illegal behavior.

Moskowitz says he made the documentary for two reasons. First, he wanted to show American audiences, who generally “have a very narrow idea of what culture is, what a proper funeral is and how to grieve,” the practice. He also wants to counter the negative perception, if not outright shame, exhibited by Taiwanese government officials, politicians and the media regarding the practice and folk traditions in general.

“As an outsider, I could lend a very different set of perspectives to a dialogue that was going on in Taiwan that was very critical of the practice,” Moskowitz said.

Photo courtesy of Marc L. Moskowitz

The academic has a penchant for the unusual, if not the macabre. His 2001 book The Haunting Fetus: Abortion, Sexuality and the Spirit World in Taiwan explored the common but little understood phenomenon of young women praying to the ghosts of aborted fetuses. At the time of its publication, Taipei Times book reviewer Bradley Winterton hailed it as “[t]he most interesting book on Taiwan I have ever read.”

Moskowitz followed it up with Cries of Joy, Songs of Sorrow: Chinese Pop Music and its Cultural Connotations (2010), a book that explores how Taiwan’s unique brand of Mando-pop offers a vocabulary to express individuality and demonstrates changing gender roles.

In an interview with the Taipei Times over coffee a few weeks back, Moskowitz expanded on his documentary, situating the practice of funeral stripping within the broader context of Taiwan’s popular religion and the controversy it often provokes.

Photo courtesy of Marc L. Moskowitz

Taipei Times: How long have people been staging stripper performances on the back of “electric flower cars”?

Marc L. Moskowitz: There are accounts of people stripping at temple events dating back to the 1800s. As you saw in the film, [Academia Sinica research fellow] Lin Mei-rong (林美容) said that strip shows in theaters were fairly common when she was a child. What is new is the portrayal of it in the press. During the 1950s or 1960s no one would have dared to report on this stuff. Now, the more titillating the better.

TT: When did the media start reporting on the performances and how has it been portrayed?

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

MM: The reporting that I looked at portrayed it as backward, local and superstitious. They saw it as a traditional culture that should be shed in favor of modern global culture. It really only hit the press and became part of the public imagination after 1980.

TT: What factors influenced this?

MM: I think there were two things going on. The economy was booming in the mid-1980s so there was a flourishing of religious events because people had money to spend on those events. Secondly, freedom of the media. During Martial Law, [these performances] were the last thing that would have been covered. I think the mid-1980s were a magical time in Taiwan because suddenly people had a lot more economic power to invest in traditional religious and other cultural venues, and also people had the right to speak about things in ways they never had before in Taiwanese or Chinese history.

Photo courtesy of Marc L. Moskowitz

TT: Did the negative press coverage exert an influence on the willingness of the strippers to be interviewed and filmed?

MM: At first it was tough because the Chinese-language media have been pretty critical of the practice, so across the board people were pretty wary of me when I first showed up. And if I err in the film, I do so more in defending the practice. I think that is because the dialogue I was engaging in at the time was so critical — things you would see on Chinese-language news that would discuss the denigration of today’s morality through this practice. The flipside of that, though, is walking down the streets of Taipei and looking at all the advertisements on the street. There is a constant barrage of semi-nudity and women’s sexuality. So if it is sexuality portrayed in the global media, well that’s fine. But if it is a local practice it becomes a point of embarrassment, knowing that the West or Japan does not do this.

Photo courtesy of Marc L. Moskowitz

TT: Does the press remain critical of the practice?

MM: Yes, I think it does. There is the perception that folk religion is aligned with superstition and exploitation in various forms. And unfortunately there are people who take this to extremes. I didn’t see this personally, but I talked to an American academic who in the mid-1980s saw a stripper essentially engaging in pantomime sex on the stage and shooting water out of her privates.

TT: Who are the biggest critics?

MM: Typically, educated males from the north, usually Taipei. I’m still not completely sure as to why that is, but I suspect it’s precisely this issue of them being a little bit embarrassed because they are worried about international and global perspectives … I think it’s a pity that Taiwan is not more proud of this, though I do understand the fear because people tend to condemn things outside the norm very quickly.

TT: Shan Ba (閃爸, the stage name for “electric flower car” manager Chiang Wan-yuan, 江萬源) briefly raised the issue of gangsterism in the film. What role do gangsters play in these kinds of performances?

MM: As Shan Ba pointed out in the documentary, it originated with gangsters. Gangsterism is such an integral part of life in Taiwan. I think it’s hard to find a restaurant that is not paying somebody off for protection. The reality is that politics are defined in part by connections and networks, which goes back to brotherhoods and lineages that date back centuries. Today, gangsters are kind of marginal in some ways and so they are dealing with marginal performances — to the degree that they are flaunting their power against authority. Who would be more attracted to that than gangsters?

TT: Right, by including strippers on the program of events, they are demonstrating their power to the public.

MM: To a certain extent they are saying: Look at what we can get away with. It attests to their symbolic capital. On one of the occasions that I was filming there were police videotaping and I was backstage and I told the manager that the police were there with a camera. He had this sort of mischievous smile on his face and he said, “You know, we are fine. We are not going to cross over any boundaries.” Other managers told me that they had been hired by politicians. Up to that point I thought that all politicians were against it. In the film we interviewed a politician who wants to control it but at the same time he’s been to those events. So even though he didn’t approve of it, he was still complicit.

TT: I found some of the songs you chose to include in the film to be quite lyrical, almost poetic. For example: “I don’t like to act sad at a bar/I’d prefer to smoke and chew betel nuts/To drink and drink until I’m drunk/Fill, fill, fill the glass to the brim.” The topic of betel nuts and drinking reminded me of hostess bars and betel nut stands. Is there a connection between those professions and funeral strippers?

MM: I think that all this stuff is on a plane. It’s not a light switch that turns off and on. It’s more like a rainbow where you are looking at different gradations of color. So I think that is right.

TT: In the film, you interview three “electric flower car” managers, three academics, two government officials and one performer — and that performer, Fang Ting (方亭), is now retired. Why isn’t there more of a focus on the strippers’ lives offstage?

MM: Initially I had hoped to get to know somebody and get to know their entire life — go to their homes, meet their families. To some degree the film was a lesson in doing what you can with what you have. As I said, at the time it was really an uphill battle. But I was really moved by how generous people were with risking their careers, given that it straddles the border between legality and illegality.

TT: Besides funeral stripping, do the women generally have other jobs?

MM: I’m not sure. My impression is that there is a whole circuit of “electric flower car” performances and the good ones work pretty much full-time. Now whether or not the others are selling betel nut by day or working in coffee shops or libraries is something I’m not fully sure of.

TT: Are the strippers paid well?

MM: How much they were getting paid seemed to be a touchy issue. My impression is that there was a big range. The people at the top of their game, like the performers at Shan Ba’s temple, were probably getting paid twice what somebody working on a small “electric flower car” would be paid.

TT: Do the girls undergo any kind of training?

MM: Yes they are trained. I know Fang Ting was one of the first, if not the very first, to introduce pole performances to the practice. And she was incredibly acrobatic. I know that she was training one younger performer to do the same thing.

A lot of the performers grew up in families that were involved in the profession in some way — trained by their parents, or older sisters or cousins. It reminds me of what European circus was like in the 1600s or a gypsy community where there is a stigma outside of the community, but within the community it is a very tight-knit group that kind of looks out for each other.

TT: At what age do the strippers begin performing?

MM: Fifteen or 16 seems to be the starting point. In the documentary, there were a couple of gals who were 16 years old. In a culture that really prides youthful behavior and cuteness, it makes sense that they would begin at this age.

TT: Have you ever seen male strippers?

MM: No I haven’t, but I’ve heard of them. I’ve seen a video online in which a guy and a gal were dancing together erotically on a large “electric flower car.” And on one occasion I saw a guy singing on an “electric flower car” outside of a crematorium, but it didn’t seem to be a performance that anyone was watching.

TT: I find it interesting that you used video as the primary medium to examine this phenomenon, rather than writing a paper or book. Do you think the video medium is becoming more common as a tool for anthropologists to conduct ethnography?

MM: I struggled with this. I think that video itself is an innately superficial medium, and compared to writing a book or article, where you can footnote every detail, there was just so much I had to leave on the cutting room floor to keep people interested. But a picture is worth a thousand words and I could have written 10 books about this issue and never given it the feel I gave in the 40 minutes of video. So there are pros and cons.

TT: How have your colleagues reacted to the documentary?

MM: I think most academics have been supportive. To the degree that people have been uncomfortable with it, I think there has been a worry that I’m promoting an exploitation of women’s bodies — naming it “funeral strippers” rather than “funeral performers,” for example, or showing women gyrating on the stage.

One or two criticisms that I received were from the perspective of worrying about the objectification of women. I think that is a valid concern. And as much as I disagree with the argument, I understand the worldview of questioning whether or not they are appropriate role models for children. But again, turn on the television and you have the same range of behavior.

My intent was to confront the audience with something that they had never seen before and change something about the way they feel about funerals. So I wanted it to be a little controversial, I wanted it to be a little bit racy.

TT: What do the funeral strippers call it? Funeral-stripping performance?

MM: The performers talk about it more as performance, and not stripping. They made a real delineation between that, and I think they are also right. But I think that putting “funeral strippers” in the title will grab the attention of those people who hadn’t heard of the practice.

TT: And funeral performers is such a broad category. It could refer to female wailers, for example, or those chanting Buddhist sutras.

MM: Exactly, and so I wanted to be very specific and I wanted to use [funeral strippers] even if people didn’t recognize Taiwan. And to be honest, that is the reason most people are going to see it.

TT: Is this an example of how the traditional roles of women in Taiwan’s popular religious practices are changing?

MM: I think there are similarities and differences, though there are more similarities than differences. The managers tended to be men who are making money, while the performers — the objects of desire — are women. As you point out, there are some fairly strong connections between that and betel nut beauties and hostess bars, and this is part of a larger cultural ethos.

On the other side, I would argue that some of these things, like fetus ghosts, are catering to what might be called women’s needs and wants.

TT: Are these funeral-stripping performances unique

to Taiwan?

MM: I think they were born in Taiwan. I’ve read a couple of newspaper articles on the mainland of similar practices popping up and the government cracking down very quickly. For example, karaoke singing at funerals is actually very common now in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). And I think that stems directly from this practice.

If you look at what is going on it is all about technology and modernity — the lights, the flashiness, even the diesel trucks and hydraulic engines going up and down. It is a wonderful mix of new and old. Some of them incorporate the latest pop songs by Jolin Tsai (蔡依林) with more traditional music. I’ve heard Japanese, English and of course Taiwanese and Mandarin songs — drawing from iconic figures and sounds from Taiwan’s particular history. This kind of range is difficult to find elsewhere.

TT: On the topic of China, commentators have discussed the possible role Taiwan’s democratization can exert on the PRC. What about folk and pop culture?

MM: Taiwan has such an incredible influence on PRC culture — ranging from music to clothing to food, and in fact religion is probably at the top of that list. People in the PRC are hungry to explore their past — the part that has been kind of erased. Taiwan has played a really pivotal role in re-introducing China to its own history when it comes to religious belief. Taiwan’s religions are very malleable and creative — there’s a lack of obsession with textual references, and these religions can adapt to new environments very quickly.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name