Among Nobel laureates of recent vintage, only Mario Vargas Llosa, who won the prize in literature last year, has delivered as much pure pleasure as Portuguese novelist Jose Saramago. Saramago’s best books read like hallucinatory thrillers. They’re warm to the touch; they practically palpitate in your hands.

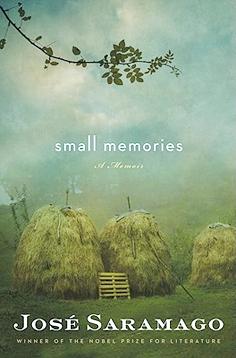

Saramago died last spring at 87. The book in front of us today is among his final compositions, a slim memoir of his youth titled Small Memories. It will not take a place among his major works. In fact — sometimes you must come right out and say these things — it’s mostly a vague and distracted book, one that provides the sensation of gazing on a dim and foggy day through the wrong end of a telescope.

Leave it to Saramago, though, to exit grinning. The most endearing part of Small Memories, a book about his childhood in the small Portuguese village of Azinhaga and then in Lisbon, comes at the very end. That’s where he deposits a small slide show of old family photographs and mischievously annotates them.

There is, for example, a photo of the handsome author in his late teens or early 20s (he looks a bit like the suave, young Anatole Broyard) with a foxy gleam in his eye. His caption reads: “By now I had a girlfriend. You can tell by the look on my face.”

Beneath another image, Saramago describes the way his mother, like a Soviet-era propagandist, used scissors to snip people she no longer liked out of family photographs. For her, he writes, “the end of a friendship meant the end of any photos too.” These photographs — they roll like credits at the end of a film — are an impish reminder of what good company Saramago has been over time.

Small Memories is a distillation of some of the central recollections of Saramago’s youth, including the death at 4 of his older brother, Francisco. But more often the memories he supplies here are, as his title implies, small but echoing ones.

He recalls the way his mother was forced to pawn the family’s blankets after each winter.

There are memories of fishing and of having fish stolen from him. He remembers watching silent movies.

Saramago licks very old wounds. About once being denied a chance to ride a certain horse, he conjures this: “I’m still suffering from the effects of a fall from a horse I never rode. There are no outward signs, but my soul has been limping for the last 70 years.”

It’s an appalling cliche to call any book a meditation on memory. What book, especially a memoir, is not that? But Saramago is obsessed here with the flickering quality of his own inner newsreel.

An elderly man looking back more than eight decades, he is right to mistrust and qualify his own recollections. But by frequently employing phrases like “I’m not inventing this” and — after describing a vivid sunset — “it really was, this isn’t a mere literary afterthought,” he manages to cast doubt over even the things of which he seems most certain. It is as if this great man were herding ghosts.

The details in Small Memories, which has been adroitly translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa, are not marshaled into a flowing, force-gathering stream.

But rich moments are to be had nonetheless.

Saramago reminds us that his surname at birth was de Sousa; “Saramago” was a family nickname — it means “wild radish” — given to the author on his birth certificate, perhaps by a drunken clerk.

It is amusing to learn that he dated a woman whose surname was Bacalhau, which means “salt cod.” They would have made delicious children.

Like a wild radish, the young Saramago was peppery. A good deal of Small Memories is a grappling with his earliest awareness of sex. A veil of myth hangs over some of these memories: hiring a boatman to cross a river to meet a girl, ogling a fat prostitute on the way to see a movie alone.

Some of the memories are more quickening. Saramago and one of his young girlfriends were “precocious sinners,” he says. At age 11 or so, he writes, “we were caught one day together in bed, playing at what brides and bridegrooms play at, active and curious about everything on the human body that exists in order to be touched, penetrated and fiddled with.”

After being caught, he recalls, he was spanked on the bottom. There is no word on whether that, too, was a Proustian delight in its recollection.

He is alert to the “friction of saddle on crotch” and to the thumpity-thump beating of hearts “underneath the sheet and the blanket” when necessarily sharing a bed with an older female cousin.

Sex gets the juices running in Saramago’s prose.

His best writing has always had an aphoristic quality, and that’s true here. “There are plenty of people out there,” he writes, “who steal much more than copper wire and rabbits and still manage to pass themselves off as honest folk in the eyes of the world.”

He notes: “The truth is that children’s cruelty knows no limits (which is the real reason why adult cruelty knows no bounds either).” And surely he is attending to literary reality when he writes, in what is probably the sentence in this book I hold most dear: “However hard you may try, there is never much to say about a henhouse.”

Small Memories has an elegiac tone, one that is suggested by something the writer’s elderly grandmother said to him: “The world is so beautiful, it makes me sad to think I have to die.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,