It was only in the last 10 minutes of my 100-minute meeting with Chang Chien-chi (張乾琦) that the respected Magnum photographer said he didn’t want the contents of the interview published.

“It’s too personal,” he said.

One might think a photographer who has trudged through China, Laos and Thailand with North Korean defectors, exposed the unsavory side of marriage in Taiwan (I do I do I do and Double Happiness), documented mentally ill patients chained together at Long Fa Temple (龍發堂) in Greater Kaohsiung (The Chain) and lived with Chinese immigrants in New York’s tenement buildings (China Town) would understand that much of what’s worth reporting on is personal.

Photo Courtesy of Anna Lisa Kiesel

As a former photographer for the Seattle Times and Baltimore Sun, a freelance photojournalist for National Geographic and gallery photographer whose primary subject is people, Chang’s bread and butter is human conflict.

Yet he spends much more time immersing himself in his subjects than I spent preparing to interview him. He lives with his subjects for days or weeks. His projects last for months or years. He eats the same food as his subjects and, as he said, “breathes the same air.”

“Photography is not part of my life. It is my life,” he said.

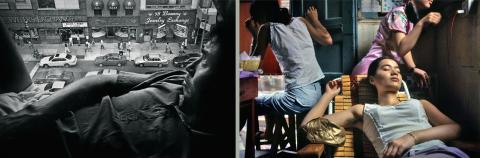

Photos Courtesy of Chang Chien-chi/Magnum Photos AND Chi-Wen Gallery

Perhaps Chang disapproved of my questions and didn’t want to see his responses in print — which I’m still trying to understand, because he didn’t say anything particularly incendiary or, for that matter, personal. Was this about control? Was the man who has made a career of observing subjects weary of being observed?

In the end, I agreed to send Chang the question-and-answer segment of this interview, indicating that we could haggle over any sensitive bits. But there were no areas of dispute and he ended up being very helpful with the photographs for the article.

Chang had just returned to Taipei from Myanmar, where he had been preparing a new project about the country’s most renowned democracy advocate, Aung San Suu Kyi. He was recently awarded the 2011 Anthropographia Award for Human Rights for a multimedia work based on his photos of North Korean defectors. Interestingly, he won it for the category of multimedia rather than photography.

Photos Courtesy of Chang Chien-chi/Magnum Photos AND Chi-Wen Gallery

Taipei Times: You were just awarded the 2011 Anthropographia Award for Human Rights for Escape From North Korea, a multimedia video based on a series of photographs you shot for National Geographic. How did the magazine project come about?

Chang Chien-chi: It was in 2007. I got a call from a photo editor at National Geographic who outlined this project for me. I didn’t initiate this — it wasn’t something that I just woke up and decided to do.

TT: Did you have any ideas about the project before you left?

Photo Courtesy of Chang Chien-chi/Magnum Photos AND Chi-Wen Gallery

CC: Yes and no. We are bombarded with all kinds of images, so I did have a vague idea. But I really didn’t have a clue what it was going to be like. I tried to read as much as I could before I went on the trip.

TT: In the end, why did you decide to take the assignment?

CC: I felt there was a thread linking this project with previous projects that I’d done — as well as works in progress and those that I plan to do in the future.

TT: Tom O’Neill, the journalist who wrote the article that accompanied your pictures, has discussed in detail his experiences traveling with defectors from North Korea. How did you and O’Neill work together in the field?

CC: I only saw him in Beijing for about 10 or 15 minutes throughout the entire trip. It was very brief.

TT: How did you communicate?

CC: Text message. A few phone calls. Working for National Geographic, for the most part, we [photographers] don’t stay very close to the reporters for a story. We kind of take our own path. But prior to that, there was the story conference.

TT: Can you give me a sense of what it was like to travel with the defectors through China down to Laos and into Thailand? Did you experience any difficulty with the police or authorities, and if so, how did you deal with these situations?

CC: I guess over the years I have picked up street smarts. It comes with the job really. If you sense there is something spooky going on you just keep a low profile. You don’t want to pop up on the grid.

TT: Did you find your self in frightening situations?

CC: Too many.

TT: Can you give me an example?

CC: You assume that you are being watched and all communications are being monitored. And then you work from there. But there are times when this was not an assumption: We were being watched. So I just thought, “Okay, let’s take it easy.”

TT: What was your relationship with the North Korean defectors like? How did you gain their trust?

CC: This trust thing is very difficult to gauge both because of the language barrier and because of the condition the defectors were in. But it was mainly through a pastor in Seoul. He was the person — and still is — responsible for bringing many defectors out of North Korea. I know I may sound a bit evasive about this, but there are things that I’m not sure I can discuss in detail. We traveled with six of them and only one agreed to have their identity revealed. In the story, they were identified by colors: One was called White, for example, and another was called Black.

TT: How long did you travel with the North Korean defectors?

CC: The job was eight or nine weeks. The time I spent on the road was over six weeks.

TT: Did you live with them?

CC: Of course.

TT: You ate at the same restaurants and stayed in the same hotels?

CC: Yeah, and we breathed the same air too.

TT: How have the North Korean defectors responded to the photos?

CC: Well, the one who was in the multimedia project was saying that he hopes that someday he can show his face, once he gets his mother and brother out of North Korea. The pastor was quite pleased with the pictures. One woman actually got some financial help because of the article. All in all, I think they were satisfied with the coverage there — their identities were never compromised and their stories were told.

TT: Are you still in touch with the pastor and defectors?

CC: Once a year — not that much now. I was in touch with them on a regular basis until 2009.

TT: How did you go about choosing the photos for the story?

CC: That was up to my editor and me. When you work for National Geographic you send them everything. In the old days, the photographers would send all the raw film back to Washington DC.

TT: What kind of narrative were you thinking about?

CC: For the most part, this was the classic photo essay — it’s quite straightforward. So if you look at the magazine or multimedia there is a thread that connects one after the other. I suppose I tried to give the viewer a sense of the difficulties of the journey.

TT: Is there a difference for you between what you do as a photojournalist and your own projects?

CC: I’m not comfortable with the term photojournalism per se. It’s in the way I approach a story. If you look at photojournalists in the field, they are sent into a situation, cover it and boom, it appears on the front page of the newspaper. But I don’t do that. Even with the assignments for National Geographic. To a great extent I would still like to do the jobs as I approach them personally. But you know everything is kind of personal.

TT: So you wouldn’t be able to work for a daily publication like the Seattle Times again?

CC: It was to a point — this was in the spring of 1993 — it was to a point that I literally had to drag myself out of bed. “Oh shit, another day.” Look, the Seattle Times and the Baltimore Sun were all good, all a good training ground. But it was just a job. Go to the office and pick up your assignments for the day, see them in the paper the next day. It was not enough for me.

TT: I saw an interview with another Magnum photographer who spoke about the role of the photographer in the field. He said that he doesn’t believe in objectivity.

CC: I’d like to comment on that. There is a danger in being too subjective because you can become too stylish. For me, this is not something that you can use a stopwatch or ruler to measure. Yes, it’s subjective, but I wouldn’t say highly subjective. I try to be accurate visually. Of course, you try to make everything within the frame fit together, to recognize a visual order in anarchy.

TT: In your opinion, what responsibility do photojournalists have to their subjects?

CC: Just try to be accurate. We are on the ground and we see what is happening. So, I think it is important, as part of this responsibility, to pursue this visual accuracy. I’m not so much concerned about style.

TT: You’ve mentioned “style” a few times — could you elaborate on what you mean by this?

CC: There are photographers who photograph something that has little to do with the subject matter. You see the photographs and say, “Ah, this must be coming from this certain photographer.” It’s just the way he or she approaches the job. It can be technical, gimmicky.

TT: So the photographer should be anonymous?

CC: It depends on the subject matter. I try to pursue it in a way that works with certain subject matter. Certain photographers put a strobe here and a strobe there and it’s almost like a light coming from god. It’s to a point where it doesn’t matter whether it was photographed in a church or war zone, or whatever. They all look very similar.

TT: So what would you consider your style to be?

CC: I don’t have a style.

TT: Going back to the theme of trust: It didn’t seem like such a big issue for Escape From North Korea because you had the South Korean pastor working on your behalf. But your China Town photos, for example, involved a lot of hard work in gaining the trust of your subjects — so much so that you extended the project from photographing the Chinese immigrant husbands in New York to working with their families in China. How did you gain their trust?

CC: I just tend to stay with the same people I photograph. It’s to a point that I know as much about them as they do about me. But it takes a lot of time. The first picture for China Town was taken in 1992 — so 19 years. And it’s still a work in progress.

TT: Is spending considerable time with a subject or subjects something you advise students to do when giving workshops?

CC: No. They will ask this question, but I don’t do that in a workshop. I tell them: Don’t quit your job thinking that you are going to pursue photography full time, right away.

TT: And yet it seems to be such a fundamental aspect of your working method. Living in the tenements with the subjects, for example, eating the same food, learning about their family situation, breathing the same air … these kinds of things. It’s as though you are an anthropologist.

CC: Well, I’m not an anthropologist.

TT: I’m not saying you are. But the willingness to live on site, to immerse yourself in the lives of those whom you document: It’s very similar to what an anthropologist does.

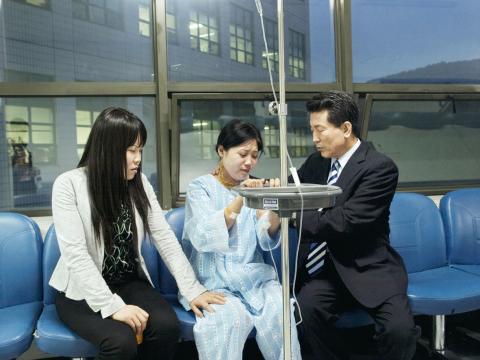

CC: Yeah, but they usually stay a couple years and they get their doctorate, and I get my photographs. It’s not just China Town. It just so happened that I started China Town in 1992. Other projects, like Double Happiness, are still going on. The Chain? Well, I can’t go back. [The Chain is a series in which Chang photographed some of the 700 mentally ill patients at the controversial Long Fa Temple (龍發堂) in Greater Kaohsiung, where patients were tied to each other in pairs as part of “therapy.” A case could be made that these heart-wrenching series of photographs made his career.] And there are another three projects that I started in 2006 and 2007 that are still going on.

TT: Why can’t you go back to The Chain?

CC: I don’t think … I just can’t go back.

TT: Why are many of your projects still continuing?

CC: I was asked this question at an International Center of Photography lecture: When do I know when a project is completed, finished? I just kind of looked at the woman who asked and said: “It’s kind of like going to the bathroom. You just know.” I guess everyone laughed — except her. It’s … look, if I feel that I have exhausted all the possibilities and I have begun to repeat myself, then I will draw a line.”

TT: You don’t seem to approach your projects with the idea that there will be an end — National Geographic assignments aside, photojournalism aside.

CC: True, to some extent. I sort of see a bigger picture with the projects that I want to pursue, the works in progress. But it is always connected to what I have built so far. With these personal projects I can sort of pace myself, do it in a way that I feel is right. And if I feel I don’t accomplish it on this trip then I will come back over and over again until I feel it is right. Unless the commission is very, very short, I will stretch it for a longer period of time and connect it to my other projects. Ideally.

TT: Are you conscious of what those connections are? What links all your photographs, or is it more of a feeling that you have?

CC: I think I only know to some extent. But another part of me is still in the process of finding the answer or answers through the exploration of different projects. It’s not so much about the untold stories — even though China Town and North Korea were both very difficult to do. I suppose it has to do with the human condition. And that condition comes from personal experience, really. Yes, I sort of have the ability to stay in tenement buildings for weeks. But I’ve lived that kind of life before, so it’s not that difficult for me. I mean, the whole experience has been evocative. I can relate to some extent and therefore I was able to stay with them. And often, I will go there and not even take any pictures — just hang out. Of course they will ask me to translate this and that.

TT: I’m curious about your shift to multimedia. Why have you gone in that direction and can we expect more of this in the future?

CC: Initially, I was interested with interviews. I started doing audio recording in 2006 with China Town because it was important for them [the subjects] to tell their own stories, their own journeys. I started doing some recording and became increasingly intrigued with sound. It was to a point that I was thinking about doing a number of sound installations. But multimedia offer another possibility to tell the story. It just so happens that I like all three media: still images, moving images as well as audio. To put them in a sequence is really a different mindset. After the Escape From North Korea assignment I went back. I had stayed in touch with some of the defectors, so I asked them about their personal experiences. Having the right subject to talk about a story, finding the right subject, the one willing to speak, was very important. I was only given 30 minutes and I went there with a translator. And it was the sound — who said this: “If a sound can replace an image, cut the image or neutralize it”? I think it was Robert Bresson.

TT: That quote sounds a little strange coming from the mouth of a photographer.

CC: Yeah, just neutralize the fucking image. Who cares? I mean a lot of people in the film industry have said that sound is 50 percent of the whole thing. Of course they are probably getting 5 percent of the budget. It’s very intriguing and mysterious, really.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern