There were crowd-pleasers at this year’s European Fine Art Fair, like a Rembrandt portrait regally displayed behind a black rope. There were also paintings by Renoir and Picasso, Miro and Warhol. But the main allure of this annual, super-size event was its breadth. Besides the smorgasbord of brand-name paintings there were arcane objects here too, like a 12th-century carved ivory chess piece about the size of a thumbnail, or a two-headed Chinese wood sculpture dating from around the third century BC. There was even a 118-carat diamond with a US$25 million price tag.

Despite recent stock market fluctuations, disasters in Japan and unrest in the Arab world, tens of thousands of art lovers flocked to the soulless convention center housing the fair to see 260 exhibitors from 16 countries show some 30,000 artworks. Fair officials estimated they would see a total of 70,000 visitors by the time the exhibition closed on March 27. That was the same amount as in past years, though the crowds seemed somewhat thinner. But if the number of private planes that landed at the tiny Maastricht airport on the day of the invitation-only preview — 60, up from 43 last year — was any indication, the event still packs in a pretty swell crowd.

Museum directors could be seen perusing the booths, including Mikhail Piotrovsky from the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia; Henri Loyrette from the Louvre in Paris; Wim Pijbes from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam; and Michael Conforti from the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Museum curators also made the trip to look at art and see colleagues, including six from the Metropolitan Museum of Art alone. And as always serious collectors came to shop. Among those seen milling around the booths: Sheik Saud al-Thani of Qatar; Stefan Edlis, an industrialist from Chicago; Mark Fisch, a Manhattan real estate developer; Agnes Gund, president emerita of the Museum of Modern Art; and Baroness Marion Lambert, wife of Baron Philippe Lambert, a member of the Belgian banking family.

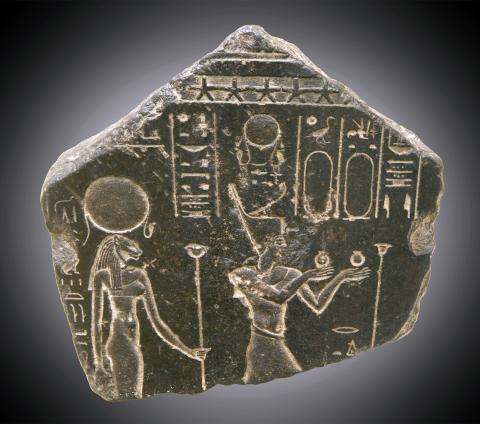

Photo: Bloomberg

For all the variety of wares it is the fine art that still gets the most attention here, with the pros on hand trying to take the temperature of the market. Getting an accurate reading is tricky, however, since dealers notoriously talk the market up. And unlike at Art Basel, the frenetic contemporary art fair held in Switzerland every June — where collectors typically make a mad dash for the booths, checkbooks in hand — buyers at this fair tend to take their time. Often deals are not completed until the weeks after the event’s end. Still, some significant sales have been reported, including a US$5 million Miro sculpture; a 1671 oil-on-panel view of Haarlem by the Dutch master Gerrit Berckheyde, priced at US$6.3 million; and a 1937 Picasso drawing of Dora Maar marked at US$2.5 million.

“There’s a huge amount of liquidity out there,” said Richard Feigen, the Manhattan dealer. “But with so much turbulence in the world, collectors don’t want to let things go, making it hard to find good material.”

Unlike last year, when there were no blockbuster offerings, this year there were a few. (Though some of the cognoscenti were grumbling that most were a bit too familiar from auctions past.) Otto Naumann, the Manhattan dealer, was offering the fair’s star, Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man With Arms Akimbo from 1658, which depicts an unidentified sitter staring, confidently, straight at the viewer. The painting, priced at US$47 million, belongs to Stephen Wynn, the Las Vegas casino owner, who paid US$33.2 million for it at Christie’s in London two years ago. “I tried to buy it at the Christie’s sale,” said Naumann, who explained that he persuaded Wynn to sell it after he read about occupancy rates plunging in Las Vegas last year.

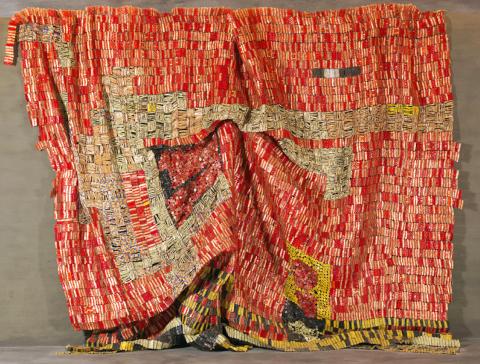

Photo: Bloomberg

On an adjacent wall was Portrait of Sigismund Baldinger, by the 16th-century German painter Georg Pencz. Naumann bought it at Christie’s in London in July for US$8.5 million; he was asking US$12 million.

While Naumann’s booth was one of many with work that has been on the market recently, the fair was not without its discoveries. Jack Kilgore, another Manhattan dealer, bought Emperor Commodus as Hercules, a painting on oak panel from 1588-1589, in December at a small European auction, where it was cataloged as only 18th-century Flemish school. Examining the meticulous brushwork, he had a hunch it was by Rubens, who had painted a series of Roman emperors, one of which was missing. Research, including consultations with various scholars, confirmed that this was it. (And the fair’s vetting committee agreed.) A collector then snapped up the painting for US$1.25 million on March 17, but Kilgore declined to identify him. “I could have sold it three times,” he said.

Several years ago the fair began beefing up its modern and contemporary art section, giving other fairs like Art Basel a bit of competition. But this year, although there were 46 modern and contemporary galleries exhibiting, the same number as last year, the selection was noticeably weaker. Gone were many of the big-name dealers like Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, Annely Juda, L&M Arts and Michael Werner Gallery, all of whom dropped out over the last few years with no heavy hitters to replace them.

Photo: Bloomberg

Still, there were a few standouts. Anthony Meier, the San Francisco dealer, for instance, had a glass case of small sculptures by Robert Gober: a red shoe (US$90,000), a Seagram’s gin bottle (US$110,000) and a wax candle (US$65,000). “There’s a huge collecting community for Gobers in Belgium,” Meier said.

Sperone Westwater, the Manhattan gallery, was showing the work of Barry X Ball, a New York artist known for using three-dimensional computer scans as well as traditional carving techniques, who is having an exhibition at the Ca’ Rezzonico museum in Venice this summer timed to the Biennale.

There did seem to be an appetite for good examples of work by proven contemporary artists. Christophe Van de Weghe, another Manhattan dealer, had red dots beside several paintings, including a 1981 Basquiat for US$2.6 million and a canvas by Christopher Wool for US$1.5 million. Both buyers, he said, were European. “Business is strong as long as the price is right,” Van de Weghe said. “It’s still a sensitive market.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has