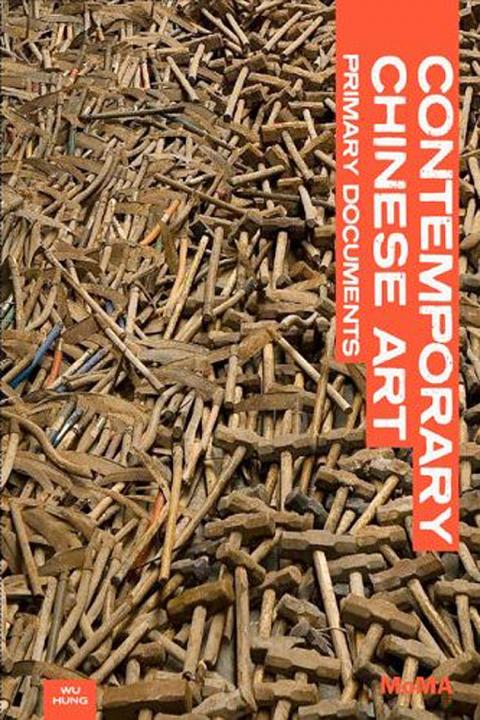

The New York Museum of Modern Art’s Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents filled me with an enormous exhilaration. It’s a large collection of texts central to the development of contemporary art in China over the last 35 years, all translated into English, often for the first time. But there’s a great deal more to it than that.

Everything about China seems to divide people. Some applaud the rise of a society until recently beset with debilitating problems, others can only see menace behind the success. But this book is different from the products of either camp. It’s entirely disinterested, it’s concerned with artists not politicians, and it mainly focuses on the young. Above all, it’s almost serenely astute, clear-headed and sane.

“No systematic introduction to contemporary Chinese art has yet been written in any language,” assert the editors (Wu Hung, assisted by Peggy Wang). Moreover, all the primary documents — artists’ manifestos, exhibition introductions, significant critical essays and so on — have up to now existed only in Chinese, frequently scattered in hard-to-find publications. This book, therefore, serves a major function in bringing this material together and to the attention of the international art world. Furthermore, additional documents are constantly being added at the project’s Web site www.moma.org/chineseprimarydoc.

By “contemporary Chinese art” the editors mean modern, experimental art as opposed to traditional art, mainstream academic art and “official art.” Thus non-naturalistic paintings, installations, performance art events, graffiti and experimental photography are all included. The book doesn’t cover contemporary art from Taiwan or Hong Kong, nor the work of artists who migrated from China before the 1980s.

The editors see the period as falling into two main phases. First came the largely domestic rise of non-traditional, non-party-political art in the late 1970s and 1980s. This was followed by the much more internationally oriented set of artists who rose to prominence in the 1990s. The editors feel the years after 2000 are still too close to view objectively, so only retrospective essays looking back to the 1975 to 2000 era are included from that decade.

The dominating impression from this material is overwhelmingly one of youthful optimism — what revolutions are supposed to generate, but in their political aspects so rarely do. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” as William Wordsworth wrote of the French Revolution, “and to be young was very heaven.”

Needless to say, the heady aspirations of China’s artists frequently met official disapproval, censorship and even persecution. Beijing’s trail-blazing China/Avant-Garde exhibition of February 1989, despite being of unprecedented size and comprehensiveness, was closed down twice, but reopened shortly afterwards on both occasions. On the first day two shots were fired, unannounced, by one of the artists, and this unsurprisingly prompted the first temporary closure. But the exhibition was radical and progressive in more fundamental ways, and the student demonstrations that erupted in Tiananmen Square three months later meant that the exhibition now stands as, in the editors’ words, “both the climax and the end of the avant-garde art movement in 1980s China.”

In April 1993 the Stamp Collecting Jeans of artist Ren Jian (任戩) were withdrawn from exhibition in a Beijing McDonald’s but were on sale in Wuhan’s department stores three months later, showing that censorship in China can be uneven and regionally based. And from 1994 to 2000 Zhang Dali (張大力) placed over 2,000 graffiti images of his own head on half-demolished houses all over Beijing, leading a clearly annoyed city official to reply to a reporter who asked him “Could you please estimate the amount of manpower spent and the fiscal burden incurred by the cleanup of the images of the head?” that numbers hadn’t been tallied and he wasn’t going to give a random figure.

But soon China’s artists were doing their equivalent of many of the things their Western peers were doing — taking photographs with the kind of old rotating cameras used to capture outdoor school assemblies, and then using color ink-jet printing technology to print them large for gallery display, riding up and down in a construction-site lift in the interests of art, and having some of your own skin surgically removed to be incorporated into an artwork.

It’s curiously instructive to be able to see the 2001 demand by Beijing’s Ministry of Culture that local authorities put an end to the behavior of “a small minority of people [who] have — in public places — been self-mutilating and abusing animals, exhibiting human and animal remains … in performances or displaying bloody, brutal and obscene spectacles under the pretense of ‘art,’” and to read it alongside the account of artist Zhu Yu (朱昱) getting a butcher to bring a side of pork into a gallery so that he could attach a bag of blood above it for an attempted infusion.

We read of Gaudy Art, a parody of the ubiquitous Chinese kitsch and “a desperate comedy for the end of the century.” Feminist art also makes a predictable appearance — “Modern art, without sober and self-knowledgeable feminist art, can only be a half-baked modern art” wrote the critic Xu Hong (徐虹). Cynical Realism and Political Pop also lead to some fascinating items.

Wu Hung is an American curator, scholar and art historian who began life specializing in traditional Chinese art but has now become an acknowledged international authority on contemporary Chinese art. Peggy Wang was, when the book was being prepared, a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Chicago, the institution where Hung is also based.

This book is refreshing primarily because of its subject matter, but also because it’s organized and written in a lucid and markedly open-minded manner. Sadly it suffers from the “smelly book” phenomenon unfortunately common to so many high-gloss-paper publications these days.

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most