After Walasse Ting (丁雄泉) fled Communist-pressed Hong Kong for Paris in 1950, he adopted his unique first name by first Anglicizing his Chinese name, then tacking on “-sse” in emulation of the famed painter Henri Matisse. Ting had little money and few connections, but within five years this son of a wealthy Jiangxi Province family had befriended a fellow artist in the abstractionist Pierre Alechinsky, who was to become a lifelong friend and would take some influence from the Chinese calligraphy lessons Ting gave him.

By 1958, Ting had sold enough paintings in the galleries of Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam to move on to the pulsating hub of the international art world of that day, New York City. There he went on to establish a studio, start a family, work hand-in-hand with legends of the era like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and spend the bulk of his life and formidable career as an abstract painter, pop poet, brilliant colorist, erotic adventurer and expatriate Chinese artist, though no single label has ever managed to stick to a man whose identity as an artist was always, to say the least, multivalent.

Preparation for Ting’s first ever retrospective, From Heroic Expression to Resplendent Color at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) until Feb. 13, began well before his death on May 17 this year, which came after eight bed-ridden years following a brain hemorrhage in 2002. Covering more than 50 years, the exhibition is probably the first to show the full breadth of Ting’s stylistic development, as well as four never-before-seen 10m canvases — they are as breathtaking as they are large — that have spent most of the past 10 years rolled up in Ting’s Amsterdam studio.

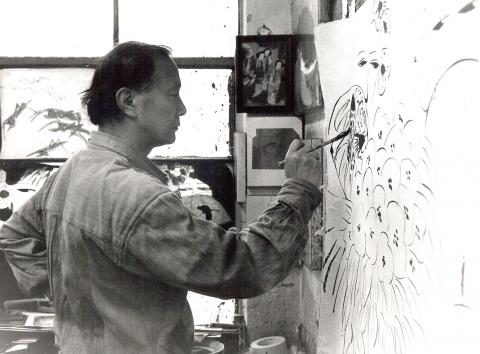

Photo Courtesy of The Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Private galleries in Taipei and Hong Kong are also mounting shows, including SOKA Art Center Taipei (The Floral Journey until Jan. 2) and Hong Kong’s Alisan Fine Arts (I Love Flowers All My Life until Dec. 31).

“What he liked was youth, vibrancy, summer, spring,” said Kuan Kuan (管管), a Taiwanese poet who became fast friends with Ting in the early 1970s. “And when autumn came, he liked the autumn that wasn’t autumn, the autumn with the flowers still blooming.”

Jesse Ting, his son, told the Taipei Times just ahead of the TFAM opening that: “He painted every day of his life. He painted on Christmas. He painted on his birthday. He would paint when we were traveling, in the hotel room.”

Photo Courtesy of The Taipei Fine Arts Museum

“Around him, you were always in the studio,” he said.

Walasse Ting was a legendary bon vivant, whose success as an artist fed epicurean tastes and colorful fancies. From the 1970s on, his paintings flowed from an almost neon palette, and he also applied garish, tropical color schemes and patterns to the suits he wore, the cars he drove and even the stories he told.

“He used to drive a Rolls Royce. If he didn’t have 10 of them, he had a dozen. That’s what he told me,” said Kuan Kuan.

Photo Courtesy of The Taipei Fine Arts Museum

A painter with a fleet of Rolls Royces?

“That’s a big exaggeration,” laughed Mia Ting, his daughter. “With my father, there were a lot of exaggerations, and to be fair, I think he prompted most of them.”

“When he had more than one — I think he had three at one time — you have to understand that these were all secondhand cars,” said Jesse Ting. “That he traded paintings for,” added Mia Ting. “He painted them green and purple. They were like Beatles cars. They lost any resale value the moment he bought them.”

Photo Courtesy of The Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Walasse Ting was born in 1929 and took some early formal training at the Shanghai Art Academy, but all his life he prided himself as a naif and an autodidact — virtues that are closely associated with modern art. He claimed his first sale of paintings came in the late 1940s in Hong Kong, where he persuaded a bookshop owner on Hollywood Road to display some watercolors, which then caught the eye of John Keswick, a taipan who exercised considerable control in south China as head of the Jardine Matheson business empire.

The Taipei exhibition begins a few years later with monochrome paintings from the mid-1950s, in which Walasse Ting attacked bare canvases with black oil paints. Despite their tremendous energy, these works seem to be caught, somewhat awkwardly, between action painting and a Chinese brush painting gone over to total abstraction. By the mid-1960s, he had moved on to painting nude female models in full color and flat, expressionistic brushstrokes, though stylistically he was still trying to find his own. (It is hard to look at the amusingly titled 1964 painting Somebody’s Wife without thinking of Willem de Kooning.) The purely abstract canvases that followed — fields of splatters and streaks — were also searching, but these had now settled on a brilliancy of palette that none of his contemporaries were able to match. Truth be told, in terms of sheer brightness, his range of bright neons is one few artists have ever been able to handle.

Walasse Ting was also writing poetry at this time, both in Chinese and in an ungrammatical English that, combined with the modern-day Zen-like riddles they presented, had the ring of pop art. A 1964 untitled poem reads:

Photo Courtesy of The Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Stomach sunk in whiskey

Pee inside pants

I saw a little star

Where is my baby tonight

It is not such a stretch to the deadpan speech bubbles of Roy Lichtenstein, who drew inspiration from comic strips and was for a time one of Walasse Ting’s neighbors.

In 1964, Walasse Ting’s poetry served as the basis of a folio of over 60 prints by 28 artists that took a title typical of pop’s notions of cheapness, One Cent Life. It included work by Lichtenstein, Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Alechinsky, Jim Dine, Sam Francis, Asger Jorn, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Walasse Ting and several others. It was a veritable who’s who of the New York scene, and it sat at a crossroads between the pop artists and the abstractionists, the Americans and the Europeans.

Sadly, these prints are not in any of the current exhibitions, and Walasse Ting’s poetry is also little represented. Future retrospectives will find ample material to work with.

Walasse Ting sat at another crossroads as well, that between the expatriate Chinese artists of that era and the Western mainstream. The photorealist Hilo Chen (陳昭宏) and the painter Dennis Huang (黃志超) were also close friends in New York, and Mia and Jesse Ting remember many others dropping by both home and studio. In Taiwan, Walasse Ting was a member of the collective that published the Epoch Poetry Quarterly, and Kuan Kuan was only one member of an expansive circle of friends.

“As my father wrote in one of his books, ‘I don’t belong to any group,’” said Mia Ting. “But I think that also hurt him, not being identified with one in particular.”

Walasse Ting’s mature painting style dates from the 1970s, at which time he applied his full explosion of color to erotic, highly expressionistic paintings of nude women that the exhibition essay quite rightly discusses in Freudian terms. He later toned down this intense sexuality, but from this time his subject matter had been distilled to a narrow range of elements: mainly women, flowers and birds, though also butterflies and the other denizens of the hothouse Eden of Walasse Ting’s florid imagination.

From the mid-1980s, Walasse Ting began painting on rice paper with thin washes of acrylic paint, and both in terms of brushwork and composition, this later work seems to call upon traditional Chinese scroll painting, becoming a sort of pop art version of bird and flower painting. Often, this is where he’s at his most magnificent.

Walasse Ting’s internationalism and nomadic identity however raise interesting questions about his legacy, and in this current spate of shows this is certainly a subtext. Will he be remembered as a Chinese Matisse, come home at last? Or as a curious wild card in the mix of New York’s pop and abstraction? His work certainly rests in the collections of the greatest museums of the West — the Metropolitan and MoMA in New York, London’s Tate Modern, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and many others — but since 1990 he largely exhibited in Asia.

That said, the question of a legacy is one Walasse Ting may not have cared much about.

“The way Walasse Ting lived life, it was almost Zen,” said Kuan Kuan. “For him, life is just like that. The most important thing was to live in the moment.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,