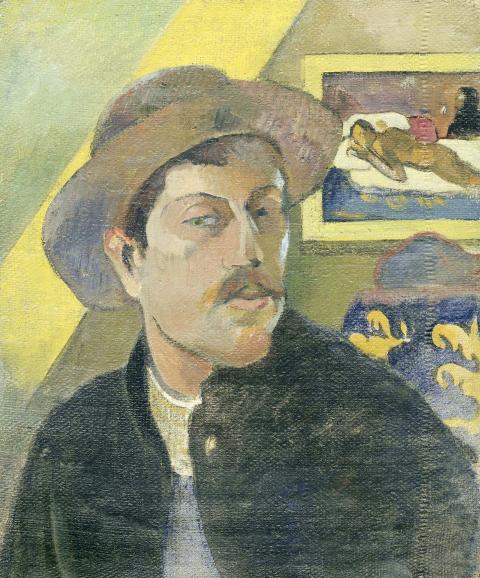

What a surprise this fresh-faced young man is, meeting you just inside the door with his level blue gaze and his pink complexion and his air of successfully balancing business and pleasure. You wonder for a minute if it can really be Gauguin, “the savage from Peru” whose image is synonymous with rebellion, escape, repudiation of all social and artistic norms. He wears the fashionable black fez of an art-lover, but with smart wing collar, black tie and suit. There’s a hint of truculence, perhaps, about the mouth, though the eyes invite you to overlook it. Almost under his chin are the little blond stubs of a beard, but he lacks a moustache, the feature that, with the hooded eyes and long, hooked nose, was to define the icon of the mature Gauguin.

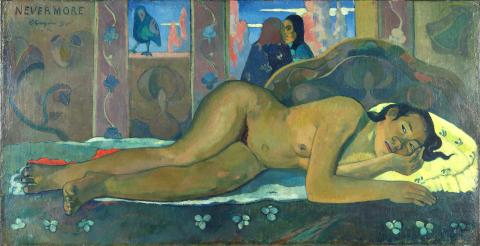

Rarely will he look us in the eye like that again. Thereafter, he angles his head (showing off that “Inca” nose) and views us askance, as people who would be lucky to get to know him. Wary, touchy, proud, sometimes slightly absurd, he becomes a wonderful subject for himself. Nine years later, embarking on the career that looks like worrying lunacy to his family, he’s pointedly wrapped in a thick overcoat, with palette beside him and the sloping timbers of a garret ceiling above. Eight years after that, at the end of his first stay in Tahiti, he poses in striped Breton jersey and polka-dot bow tie with a Polynesian idol looking on: a cultural eclectic with hand on chin as if to say, “What do you make of that?” Back in France a few months later, he has his traveler’s hat on and the slope of the ceiling has turned to gold — a bar of the intense yellow Gauguin loved; hanging behind him, in reverse, is the major work of those travels, the disturbing Manao Tupapau, in which a naked teenage girl lies face down on a bed, watched over by the black-swathed Spirit of the Dead. In all these self-images, the invitation to admire the artist is hedged with defiance — the boast about Manao Tupapau is part artistic, part sexual braggadocio about the kind of teenage “bride” available to the exotic traveler he had become. In Christ in the Garden of Olives he takes it dangerously far, appearing as a scarlet-haired Jesus, brightly lit against a dark background in which shadowy figures are glimpsed approaching. Throughout there is an unavoidable sense that a good deal of Gauguin’s self-projection was, precisely, a pose, yet one that confounds our sense of the poseur by the repeated production of works of genius.

In Manao Tupapau we understand that the crude black idol at the foot of the bed, very evident to us, may nonetheless be simply a projection of the sleepless girl’s terror — her head on the pillow is turned away from it, towards us, and her eyes convey an incalculable blend of passivity, accusation and fear. It’s a large bed she lies on, on the very edge, with space beyond her where someone else has lain, and will do so again. If the magnetic oscillation in the painting of her body, between the eyes and the pink highlight of the cleft of her buttocks, is uneasily pornographic, Gauguin was understandably at pains to emphasize the strong but ambiguous air of the metaphysical that permeates the picture. In the mauve night beyond the bed, indecipherable forms and phosphorescences seem hints of both natural and supernatural worlds. The power of the painting lies in part in its confusing but irreducible mixture of motives.

Photo courtesy of THe Tate Modern

Gauguin — whose affinities with the symbolists were deep — had already explored a simultaneous depiction of the real and the imaginary in The Vision After the Sermon, painted four years earlier in Brittany, where the praying peasant women and Jacob wrestling with the Angel are shown together, the broad diagonal of a tree trunk dividing the two arenas of experience. It is a spectacle that all but one of the women observe with their eyes closed. Clearly a large rich history of the depiction of saints’ visions in Western art lies behind the painting, but Gauguin has wrenched it into a new configuration by his stylized flatness of treatment, boldness of design and the astounding vermilion field against which the vision is seen. Though he repudiated Christianity, Gauguin’s eye for visionary experience was that of a mystic as much as of an anthropologist of “primitive” beliefs.

He had also made more intimate and domestic approaches to the threshold of dreams, in haunting pictures of two of his children asleep. In The Little One Is Dreaming his daughter Aline lies turned away from us, upper body huddled in nightclothes, legs out in the cold, while above the black dado rail behind the bed, dark leaves and birds swoop in the green, as though the wallpaper had come to life. The pointy-capped jester of a doll by the bed head is less frightening than the Spirit of the Dead, but nonetheless vaguely malign — the clownish plaything that is also the impresario of her dreams or nightmares.

There’s a doll, too, in the picture of his son, Clovis Gauguin Asleep, the face blurred as if by sleep, the blue vertical brushstrokes of the wall beyond ridden over by whirling forms of creatures or flowers. Clovis’ hand stretches out, as if for reassurance, to a huge carved tankard. This — 18th-century, Norwegian — is displayed close by in the new exhibition at Tate Modern, giving the viewer, too, a vaguely uncanny sense of being within reach of the dream.

Photo courtesy of The Tate Modern

Dream isn’t always the right word to convey the mysteries and disjunctions in a Gauguin painting, in which there’s frequently something unexpected going on. The pleasant many-colored apples in one still life sit on a white cloth beside the more troubling organic form of one of his own brown ceramics, the ensemble surveyed at close range by the bespectacled profile of his friend Charles Laval, so that one genre seems to have invaded another, the result being a sort of oblique conversation between the two artists. (It was with Laval that Gauguin was shortly to make the visit to Panama and Martinique that would be a turning point in his art.) In the busier Still Life With Fruit three years later, the spread of fruit is inspected at even closer range by the apple-green face of a hungry and impatient child. And in the captivatingly eccentric Still Life With Three Puppies, in a steeply sloping picture-plane, the puppies at the top, puce and tan and gray, lap milk from a pan, while in front of them on the patterned tablecloth three blue wine glasses stand, with a plum placed by the foot of each one, and in the foreground a round bowl and platter of pears complete the composition. The pears and puppies show the fondness for cusped forms that recurs in Gauguin — leaves, distant trees, clogs, animals’ tails, leaf and fruit patterns on fabric — and a mysteriously calculated still life (the glasses and plums prepared for a formal dessert perhaps) is offset by the very wriggly life of the guzzling dogs.

The ravishing nonchalance of design, like a fore-echo of Matisse, is seen, too, in Gauguin’s powerful Te Faaturuma, one of the most refined of his earlier Tahitian paintings, where the natural temptation to tropical exuberance of detail and palette is curbed into something more austere. The cross-legged young woman is like many others Gauguin painted in Tahiti and the Marquesas, but here invested with a peculiar heaviness and somberness of mood, chin on hand, staring at the simple still life of round forms in front of her (straw hat, bowl with burning incense, delectable swirls of fruit) with none of our appreciation for how perfectly they’re painted. The floor of the room is an uninflected plane of pale

orange. And beyond the open porch, where a black dog like a hieroglyph is sitting, a small green glimpse of forest floor, and a man on horseback, waiting. Who he is,

and whether he is indeed there, goes, of course, unexplained.

Such figures on horseback, men in mysterious freedom of agency and movement, recur in the background of Gauguin’s Polynesian pictures, the miniature landscapes glimpsed beyond the torpid and often melancholy world of the women. He wasn’t uninterested in the Polynesian male as a subject (it’s a shame perhaps that the Tate show has none of his pictures of the man called Jotefa, a young woodcutter with whom he describes a mystically sensuous experience in his book Noa Noa). But it is clear even in his earliest tropical paintings, from Martinique in 1886, that what entranced Gauguin was the inscrutable va-et-vient of the women’s day, figures laughing and conversing in a language he could barely understand, the further language of gesture and glance taking on a heightened significance. (At the Tate there’s a room devoted to Gauguin’s Tahitian titles, and their often bafflingly enigmatic nature, as if he wished to show us, too, what outsiders we are, and how thoroughly conversant he has now himself become.)

In his later life Gauguin seems to have felt less inclination, or need, for the self-questioning and self-assertion of the self-portrait. But he looks us straight in the eye again in the last self-portrait he ever did, in the Marquesas, in 1903, a spare sketch of a painting abnormally subdued in color: blue-gray background, white (in fact cream and beige) hospital smock, blue eyes somber behind spectacles, the face dark brown. If the liberation of color was one of Gauguin’s most exhilarating attainments, here he seems almost to abjure it. His skin is not the yellow or golden brown of the islanders he’s painted since his arrival in Tahiti 12 years earlier, nor is it the ruddy tan of a northerner gone native; it’s the strange earthenware brown of a Fayum funerary portrait, and it adds incalculably to the image of unadorned stoicism, a man stripped of all accoutrements, confronting the viewer as he confronts death.

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled

Dull functional structures dominate Taiwan’s cityscapes. But that’s slowly changing, thanks to talented architects and patrons with deep pockets. Since the start of the 21st century, the country has gained several alluring landmark buildings, including the two described below. NUNG CHAN MONASTERY Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山, DDM) is one of Taiwan’s most prominent religious organizations. Under the leadership of Buddhist Master Sheng Yen (聖嚴), who died in 2009, it developed into an international Buddhist foundation active in the spiritual, cultural and educational spheres. Since 2005, DDM’s principal base has been its sprawling hillside complex in New Taipei City’s Jinshan District (金山). But