At 10am on May 25, I was nestled into the deep plush of a velvet sofa three floors above Bond Street in central London with a mustached architect dressed head to toe in eyewateringly tight black leather. He talked in a breathy, conspiratorial whisper about philosophical happiness and had me bend down to join him in lovingly stroking the carpet, which, he told me, was woven in a little workshop he owns in the Caribbean. In a changing room nearby, everyone from old-school aristocrats (Lady Helen Taylor) to latest-edition paparazzi-darlings (Daisy Lowe) was wriggling in and out of dresses, choosing which “looks” to borrow for a glitzy dinner in the evening. On the ground floor, uberstylist Katie Grand was holding court in pink sunglasses while a cleaner flicked non-existent dust from a case containing Princess Margaret’s luggage. A moving sculpture by the artist Michael Landy entitled Credit Card Destroying Machine (component parts: antlers, teddy bears, rusty tools; and yes, it works) whirred away by the glass doors outside which Alexa Chung, in the midst of getting ready to host a live feed of party arrivals on Facebook, was having a cigarette break.

Welcome to the new Bond Street palace of Louis Vuitton, which takes the dark art of luxury retail to a new level. For starters — despite the racks of handbags, luggage and clothes — this flagship, which opened to the public on Friday, is not — repeat not — a shop. I was told many, many times before I even set foot in this three-years-in-the-making temple to the Louis Vuitton brand that it is a maison, not a store: “Reflecting Louis Vuitton’s art-de-vivre and savoir-faire, conceived as the home of a collector ... [it] gives visitors opportunities to discover new and exciting experiences.”

Which is daft, of course. But then the Louis Vuitton belief that retail is about emotion looks less and less silly with every set of figures the company releases. LVMH, the fashion house’s parent company, reported 11 percent sales growth in the first three months of this year, rewards reaped from audacious global expansion — last month, two new Louis Vuitton stores opened in Shanghai in one day — and from a strategy of focusing on the brand’s heritage in a more glamorous age of travel, which has hit a chord with customers. Research in Japan, where 60 percent of households own a genuine Louis Vuitton product, suggests consumers are prepared to pay 50 times as much for the real thing as for a fake, even if the products appear identical, because of the feeling of “specialness” they get when they purchase the real thing.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

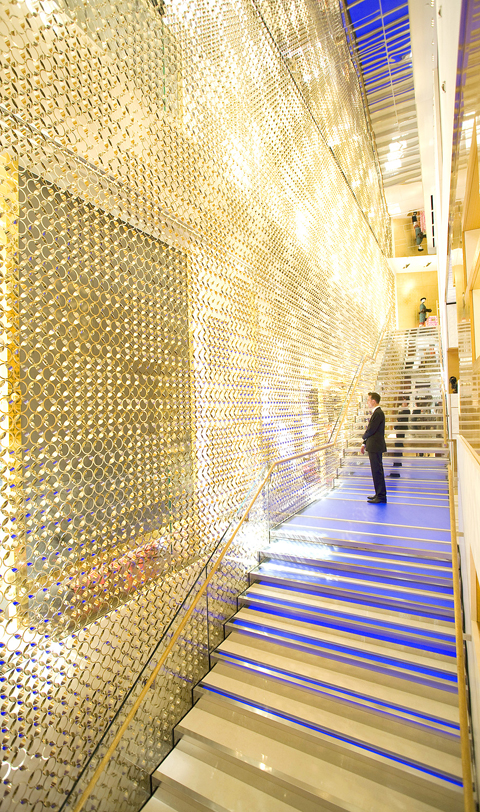

The glass front of the Bond Street store is lined from floor to ceiling with a monogrammed golden chainmail that filters a sunny light on to the shopfloor. Facing you as you enter is a custom-made travel caviar set, in crocodile. (There is, of course, nothing as vulgar as a price tag.) Beyond, there is a wall of vintage trunks and another of current season luggage. The “bag bar,” where you can sit on a leather barstool and watch a moving display of handbags behind the counter, was inspired by the shooting-duck gallery of the funfair. (With Kiki, a giant sculpture by Japanese artist Takashi Murakami next to it, it also looks a little like a conveyor-belt sushi bar.)

At every turn, the boundaries between art and fashion are deliberately blurred. A huge self-portrait by Gilbert and George hangs between the two walls of men’s tailoring; in the exhibition space, Katie Grand, a longtime collaborator of the Louis Vuitton designer Marc Jacobs, has curated an exhibition of catwalk fashion. In the “library,” Barry Miles’ book, London Calling: A Countercultural History of London Since 1945, sits alongside limited-edition artists’ notebooks with covers by Gary Hume and Anish Kapoor. The top-floor “apartment,” where specially invited guests can make their selections in private, boasts a Basquiat, a Koons, another Gilbert and George, and two Richard Prince pieces.

Amid the walls of glossy bamboo and others wallpapered in silk and then hand-papered on-site with silver lacquer, and the hand-carved marble monograms sunk in the floor, architect Peter Marino cuts an improbable figure. He is dressed in his trademark biker leathers (custom-made at Dior), and completes the look with a cap and moustache. Marino, a flamboyant figure in the fashion world since his first job renovating a New York townhouse for his friend Andy Warhol, has become the go-to guy for jaw-dropping luxury flagship stores, including the Chanel Tower in Ginza, Tokyo, and the Christian Dior flagship in Paris.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Just don’t call them luxury. “I am totally throwing up over the L word right now,” says Marino, who alone among the smooth, money-oiled LVMH machine is gloriously off-message. “The PR department will keep pushing that word, but since when did retail have to be so self-important and serious?” When Marino was first approached for this project, he refused — because he had designed the previous Louis Vuitton store on the same site, legend has it he said it would be “like eating my babies” — but he changed his mind. Are you happy now, I ask him? “Do you mean philosophically, or emotionally? I think maybe I’m too old now to be happy emotionally. But I try to be happy philosophically.” Actually, I say, I meant the store, do you like it? Marino throws his head back and laughs; his assistants and PR, hovering behind him, shoot nervous glances, clearly dying to rein him in. “The store! Of course. That’s hilarious. The thing is, I just want somewhere I feel good, a nice place to be, somewhere my wife would buy a handbag and then not be dying to get the hell out straight away. You know what I mean?”

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,