Paul Theroux has published 47 books in 42 years, and inevitably some of them are less good than others. I’m an enormous fan of his work, and few modern publications have given me as much pleasure, despite their not infrequent bad temper and mockery, as My Other Life, Millroy the Magician, Hotel Honolulu, The Elephanta Suite, Riding the Iron Rooster, The Pillars of Hercules, The Happy Isles of Oceania, Sir Vidia’s Shadow, Dark Star Safari and, most recently, Ghost Train to the Eastern Star. But this new novel is by and large a disappointment, everywhere slightly unsatisfactory and, by the time you reach the end, unfulfilling in a wider sense.

A Dead Hand tells the story of a middle-aged American writer of magazine articles marooned in Calcutta and unable, through an unspecified malaise, to put pen to paper. Out of the blue he receives a letter asking him to investigate a crime — the dead body of a young boy planted in a cheap hotel room, rolled up (he later learns) in a carpet. The hotel guest, a young Indian, has fled in terror. Could he help clear him of suspicion, or at least throw some light on the crime?

The novel’s main character is the writer of the letter, a Mrs Unger, an American who runs a home for desperately poor Indian children,

and who refuses all publicity with a saint-like modesty. The narrator becomes devoted to her and her cause, addicted to her Tantric massages, and even makes some progress in his investigations.

It’s hard to demonstrate the novel’s unsatisfactory nature without revealing the ending. Suffice it to say that the fact that Mrs Unger is other than she seems will be obvious to every reader from the first few pages. And yet Theroux piles on details of the narrator’s innocent obsession as if in an attempt to drive the reader crazy with frustration. “Surely the fool can see she’s not what she appears,” we groan. “Why does he persist in being to naive?”

And yet the conclusion, when it arrives, is unsurprising and only mildly interesting. Writers of detective thrillers such as P.D. James would never have been satisfied with so unstartling a denouement. It’s almost as if Theroux is unable to abandon a book once he’s embarked on one. And the plot material of A Dead Hand would be more suited to a long short story than to a full-length novel.

Indeed, the Theroux book this new one should be compared with is The Elephanta Suite [reviewed in Taipei Times, July 20, 2008]. This set of three concise and incisive novellas set in India has everything A Dead Hand lacks, as well as containing the gist of Theroux’s savage criticism of modern India, to which this new book has little substantial to add (perhaps fortunately). Those three brilliant stories had pace, drive, drama and tension. A Dead Hand, sadly, lacks all these things.

It’s as if Theroux, having already delivered three brutal kicks to India, not to mention additional mockery last year in Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, sensed there might still be life in the victim, and so resolved on one final assault to finish the place off once and for all.

This is not to say that abuse of India is at the heart of the novel. Pity also has its place. There’s nothing Indian about the mysterious Mrs Unger either, although you sometimes feel that she might have been made an Indian in some earlier draft — a “confession” made on a long train journey, with no obvious plot-related point, tends to support this hypothesis.

All in all, there’s something structurally awry here. Was the novel initially plotted rather differently, then completed with the undigested material insufficiently changed? Probably not, considering Theroux’s general professionalism. But haste does seem to be a part of the problem, together with a determination to push ahead with unmalleable material come what may.

Many of the utterances of the narrator, and of his friend at the US consulate, appear to incorporate Theroux’s own caustic views on India with little adjustment. As if this wasn’t enough, the real-life Paul Theroux himself appears as a character. “Paul Theroux wants to see you,” says the consulate friend. “He’s in Calcutta.”

This is a smart move on Theroux’s part, possibly the only one in the novel. Of course there’s only one way the famous writer can be presented, and that’s hostilely. He could hardly be shown as a great man uttering witticisms and beaming bonhomie. So he’s mocked. He’s considered by the narrator to be a “smirking, intrusive, ungenerous and insincere man,” with “the heartless and unblinking gaze of a hunter lining up a prey animal through a gun sight.” He’s seen as smug, someone on the make, competitive and inquisitive. The narrator is enormously relieved when he leaves town.

What’s Theroux up to here? Maybe he’s exorcising the version of himself he sees in nightmares. There’s little doubt that the narrator, too, is Theroux in all but name, so the “real” Paul Theroux who shows up, briefly but memorably, can only be the “other self” who the author wants to identify accurately in order to, in some sense, be rid of.

Of course there are enjoyable things in this book. Theroux may be cutting, but he’s also deeply perceptive — a man who penned some of the best criticism of Salvador Dali in existence when visiting the surrealist’s home in The Pillars of Hercules could hardly be otherwise. If this book were written by someone else it might deserve muted praise. It’s only in comparison with Theroux’s best work that it’s more than a little disappointing.

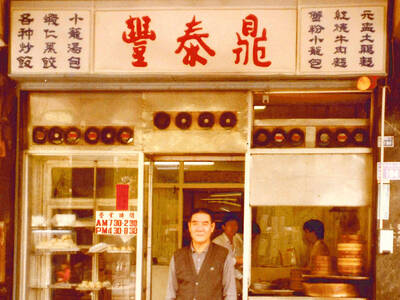

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern