Jane McAdam Freud put the father of psychoanalysis on the couch for 20 months.

Well, sort of.

In 2006, McAdam Freud, daughter of British painter Lucian Freud and great-granddaughter of Sigmund Freud, was granted an artists residency at the Freud Museum in London where she spent just under two years analyzing her iconic ancestor’s life and his collection of more than 2,000 objects dating as far back as ancient Egypt. It also served as a means of exploring her own artistic self.

The result was an exhibit and book, Relative Relations, as well as a film, Dead or Alive, that documents the work she created during her residency. A screening of the film will open Old Dreams, New Interpretations — An Artist’s Perspective, a talk by McAdam Freud this Saturday at 2pm.

The talk, co-organized by Taipei’s German Cultural Center and the Lung Ying-tai Cultural Foundation (龍應台文化基金會), will be held at Zhongshan Hall as part of the MediaTek lecture series.

Taipei Times: In what ways has your father influenced your art and how does this complement/differ with your great-grandfather?

Jane McAdam Freud: My relationship to Sigmund and Lucian is something I cannot now deny or escape, so I have learnt to embrace it in my life. It has a continual impact on my life in many ways, genetically, psychodynamically and emotionally. The impact my relationship to my father and great-grandfather has on my opportunities in the art scene, I would say, is more of a hindrance than a help.

The name Freud is a sort of “object.” It is owned by many: the psychoanalysts, the artists and the relations. They are all possessive over the public object. He [Sigmund and Lucian] and his name are a sort of public object and each group wants to own him as theirs, psychodynamically speaking.

This makes it all the more important for me to maintain my own identity and not to get lost in all of that.

(McAdam Freud trained at the Royal College of Art, London and was awarded the British Art Medal Scholarship in Rome. Her work is held in many international and national public collections including the British Museum and National Gallery Archive and is on permanent display at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her depth of knowledge and extensive experience as a medalist has led to positions of engraver to the Royal Mint and chief sculptor at Australia’s Perth Mint. The 51-year-old artist works in a variety of mediums including drawing and print, sculpture and medals and film and digital media.)

TT: In the book Relative Relations, you examine the similarities between your art and the antiquities collected by your great-grandfather. Why do you see this as important in your relationship with him and your art?

JMF: Well, you have to realize that I was unaware of Sigmund’s collection before the year preceding my artist’s residency at the Freud Museum. I found it extraordinary that I had made so many works that were so similar to those he had collected. I am a contemporary artist and Sigmund Freud collected ancient sculpture. However the nature of the objects he collected bore resemblances to things I had made over the past 25 years.

I was driven to continue with the medium but it was unexplainable to me and others. I continued with it like an addiction. Sigmund Freud said that he had two addictions, one was nicotine and the other was his collection of antiquities. Freud also collected many portrait busts. Portraiture in sculpture was another area I felt compelled to master. Both these facts I found uncanny!

TT: Did [the residency] enable you to see your art in a new light?

JMF: Oddly it cured me of my addiction and as a result I was … free to produce works in any/all dimensions and media. It was important for me to know that the precedent for my predilection came from my great-grandfather. His blood seemed to be singing in my veins at least as far as our desire for sculpture was concerned. He collected sculpture and I make sculpture …

It enabled me to make art in a freer way — that is, without the unexplained restrictions. I feel that my art is less anal now and I prefer the relationship I have with my working processes.

TT: How did these objects help you connect to those artists of the past?

JMF: Just being with his ancient objects helped me familiarize myself with them. Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Chinese ancient sculpture surrounded me for 20 months. This itself was an education. It is rare to see such objects outside of a museum setting. It is even rarer that one gets the opportunity to handle such objects. I did this with many of the objects for long periods of time, scrutinizing and drawing them. I understand ancient sculpture in a way I could only have dreamt of before.

To place my sculpture in my own past, in my ancestral home alongside their precedents was a rooting experience for me and for my art.

TT: Which of your great-grandfather’s theories has played an important role in your work?

JMF: Sublimation is interesting as it is Freud’s theory of art as a defense mechanism. Sublimation is one way of dealing with conflicting feelings, which can in some cases lead to neurosis. Sublimation is a type of defense mechanism to prevent mental conflict becoming too acute. It is a channeling of the sex drive into achievements like making art, writing poetry, science etc — a socially acceptable way of dealing with these drives where displacement serves a higher cultural purpose, one that is socially acceptable.

TT: You mention that the processes of psychoanalysis and of art make use of the unconscious. Please expand on what you mean by the unconscious and discuss its relationship to the process of creating your art.

JMF: There are two terms used by Freud. One is the “subconscious,” and this refers to information that can be recalled albeit with difficulty. The other is “unconscious,” referring to repressed information that is, for all intents and purposes, forgotten. By unconscious I mean unknown, once known, hidden knowledge, repressed knowledge. I think artists use this knowledge and the viewer taps into it in his/her engagement with art.

TT: What of art in a more general sense?

JMF: Freud’s recognition of the unconscious was very important for the comprehension, growth and development of contemporary art in general. As a result my art can exist and develop. I can make conceptual art. It is socially and culturally acceptable. In fact I feel that Freud, with his theory of the unconscious, opened the doors to conceptual art practice and this is very important for me as conceptual art is the movement I align myself to.

TT: Who are your artistic influences?

JMF: I love Duchamp and the American conceptual artists like Bruce Nauman and Joseph Kosuth. When I met Joseph Kosuth he told me that he was inspired by Sigmund Freud. What I admire about them is their use of language and visual symbols in art. In my own work I have always used symbols and language. I think that is what attracted me to the medium of the medal, which I worked with a lot initially.

TT: You’ve participated in Art in Action [where artists demonstrate and discuss their techniques with the public]. What is it and why did you participate?

JMF: Art in Action is about doing the thing I like best, making art, and doing it with people around. It is often very lonely being an artist … But I hate being alone. It is a contradictory state and the way I deal with it is to have people around me once a week. I open my studio to students for one day where I carry on my own project while they also do their own work.

TT: What do you get out of Art in Action as an artist?

JMF: It is important to connect with people. We all need people. At Art in Action it is another opportunity to balance out the usual day-to-day isolation. It is exhausting performing for two full days and being asked questions. But at the same time, when it works and people get it, it feels exhilarating and addictive.

TT: What do you think the public walks away with?

JMF: I think people feel the same thing I do when I make a piece. They look at something and it speaks to them on a visceral level and they understand something they did not understand before in a language not spoken. Neurologically speaking, the information goes straight to the heart, the gut or some other place where the unconscious may reside. The public I hope may walk away with something new.

TT: What is your process of creation?

JMF: I have the thought, the idea and then I seek out a way of expressing it but more often than not the process seeks me out. For example, sometimes I feel really restless and just get up and make or draw and that is a response to concepts I am mulling over. Other times I sit with an idea for a project and see how important it is by seeing if the ideas and desire to make something of them stays with me for a period.

TT: You recently re-titled yourself as an artist: 2D, 3D and 4D. What is this transformation, and why did you undergo it?

JMF: I don’t like to be pigeon-holed and notice that as soon as I am labeled I want to escape. In 1993 I embarked on a MA project at the Royal College of Art. I entered into the broadest program that I could manage which involved fine art, sculpture, bronze casting, silversmithing and ceramics. I wanted to learn many skills.

At that time the idea of multi-disciplinary did not exist. The college however proved to be an open and “multi-disciplinary” experience for me.

When I started making video it seemed that the work had become multi-dimensional too. The strange thing with the title you refer to which I use on my Web site “Artist 2D, 3D, 4D” is that it leaves out the most important dimension to me which is 2.5D. By 2.5D I mean two-and-a-half dimensional works. They are not works in the round but instead they operate in relief format. They employ the use of two sides, a distinct back and a front. Front and back implies the existence of the side and I like to play with these ideas. The psychological overtones of the interplay interests me.

TT: What projects are you currently working on and in what way does this continue your past work and, perhaps, move beyond it?

JMF: I am preparing for an exhibition with “interfaith” overtones. It is called Otherside. This title refers to the process I favor which is making objects with 2.5 dimensions. That is, objects with two distinct sides. Otherside embraces all the connotations of the phrase, with its poetic and political resonances. It relates to the other side in a Freudian dualistic sense. “One side infers the other.” There is always another side to everything, another option, and another way forward. My works for this show displays traditional sculpture but through symbolic placement of the pieces and distortions of the form evoke some poetic/provocative questions.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

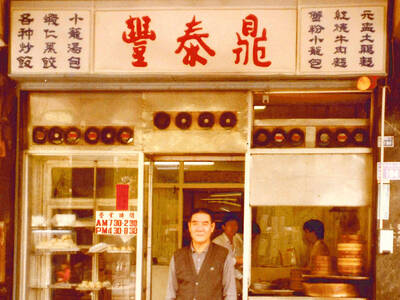

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern