It's Christmastime in Kenya in An Ex-Mas Feast, the first short story in Uwem Akpan's startling debut collection, Say You're One of Them. The narrator is Jigana, an 8-year-old boy. His 12-year-old sister is a prostitute, which makes her Jigana's most fortunate family member by a long shot. His 10-year-old sister wants to follow the older girl's example. There are also 2-year-old twins and a baby who's used as a prop for begging. The family’s most precious Christmas gift is a container of sniffable glue.

These conditions are so dire that it’s possible to misunderstand the author’s tone, at least initially. An Ex-Mas Feast is so relentless that it almost has the makings of macabre humor. Only after the patriarch has been able to steal a cache of party presents, including gift-wrapped insecticide, and trade them for dubious treasure (zebra intestines and three cups of rice) is it clear that Akpan is not striving for surreal effects. He is summoning miseries that are real.

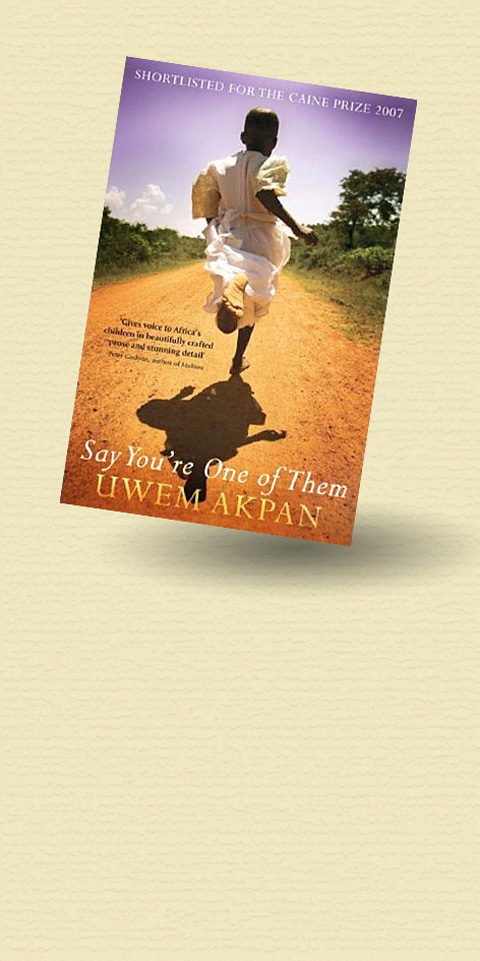

Ever since An Ex-Mas Feast appeared in The New Yorker’s 2005 debut fiction issue, Akpan has been received as a critics’ darling. A Jesuit priest with an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan, he is comfortable on many kinds of terrain. He fuses a knowledge of African poverty and strife with a conspicuously literary approach to storytelling, filtering tales of horror through the wide eyes of the young. In each of the tales in Say You’re One of Them a protagonist’s childlike innocence is ultimately savaged by the facts of African life.

If Akpan reiterates this same idea, he does it in widely varying locations and formats. Two of this book’s five pieces are novella-length; the other three stories are relatively short. Geographical references include Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda and Gabon.

This last country is the supposed destination of the brother and sister in Fattening for Gabon, and it takes many pages for the children to grasp what is signaled to the reader early on. Kotchikpa and Yewa are not bound for a life of wealth and happiness in the country of the title. “Selling your child or nephew could be more difficult than selling other kids”: that is the blunt line with which “Fattening for Gabon” begins.

But their uncle, known as Fofo Kpee, cons these children with a flashy motorbike. He says it’s a sign of the life they will have when they sail from Benin to Gabon. Since the children have long been separated from their parents, who have AIDS, the motorbike looks that much more tempting. Akpan is at his bleakly surreal best when he loads the bike with five people, along with yams, pineapples, oranges, a rooster and five rolls of toilet paper for a joyride.

“My chest swelled with pride,” says Kotchikpa, “and my eyes welled up with tears, which the wind swept onto my earlobes.”

Imagery like that is far more vibrant than the mechanical ways in which these stories move toward doom. With his trajectory always a fait accompli, Akpan fares better with small, evocative details than with broad strokes. The phony new caretakers who ask Kotchikpa and Yewa to call them Mama and Papa, and who ply the kids with foods that will make them more valuable as slaves, can be little more than caricatures. Far more memorable is one of the feasts these people provide.

“A pot of pepper soup was studded with chunks of bushmeat, each held together with white string, some of the meat still carrying the pellets that had brought down the animal,” Kotchikpa observes, “which was the kind of stuff our people liked a lot.”

Akpan uses dialect to strong effect. (“Joy full my belly today because my broder and wife done rewarded me, say I do deir children well well,” the treacherous Fofo says of his value as an uncle.) Throughout this collection he succeeds far better in summoning individual voices than in capturing more generalized conflict. In An Ex-Mas Feast, which is still this author’s most audacious story, the matriarch of Jigana’s street family comes fully to life only when the family starts fighting. “This boy has grown strong-head,” she says of her son. “See how he is looking at our eyes. Insult!” Akpan also sets his scene vividly with “loose cobbles that studded the floodwater like the heads of stalking crocodiles in a river.”

The most ambitious story is Luxurious Hearses, a crowded microcosm of Nigeria in turmoil. The title refers to the bus on which the teenage protagonist, a Muslim named Jubril, hopes to escape into Niger. But to travel safely, he must pretend to be a Christian. Jubril’s disguise is compromised as much by his aversion to secular influences like television and “hell-destined women” as it is by the fact that he has had his right hand cut off as a form of Sharia punishment.

When Akpan stalls the bus in limbo and loads it with a cross-section of passengers, many of the forces that roil African nations are represented. Religious war, tribalism, the power of the military and the influence of oil money are among the many facets here; conflicts in Liberia and Sierra Leone are among those specifically invoked. Despite such dramatic density, the arc of the story is as self-evident as the epiphany that comes to Jubril.

“He felt connected to his newfound universe of diverse and unknown pilgrims, the faceless Christians,” Akpan writes. “The complexity of their survival pierced his soul with a stunning insight: every life counted in Allah’s plan.”

Akpan makes the lives of children count most of all. In the title story a Rwandan girl of mixed Hutu and Tutsi lineage witnesses the most horrific sight any child could ever see. In the face of an encroaching bloodbath, “Say you’re one of them” is a command from a desperate parent. The girl is being told to do what, in these stories, is all but impossible: Find a way to stay alive.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu

Feb 24 to March 2 It’s said that the entire nation came to a standstill every time The Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠) appeared on television. Children skipped school, farmers left the fields and workers went home to watch their hero Shih Yen-wen (史艷文) rid the world of evil in the 30-minute daily glove puppetry show. Even those who didn’t speak Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) were hooked. Running from March 2, 1970 until the government banned it in 1974, the show made Shih a household name and breathed new life into the faltering traditional puppetry industry. It wasn’t the first