Early last year, marketing executives at Totes Isotoner, a Cincinnati company that had spent the previous 30 years churning out a reliable lineup of humble umbrellas, crowded around a computer and listened to a teenage singer from Barbados named Rihanna breeze through a tune titled, appropriately, Umbrella.

The song, not yet released, had commercial, jingle-ready lyrics and a stick-in-your-head hook: “You can stand under my umbrella, ella, ella, eh, eh, eh.” Totes, which hadn’t deployed celebrity endorsements since the former NFL quarterback Dan Marino hawked its gloves more than a decade earlier, was smitten. Umbrella became a corporate rallying cry, with the song drifting through Totes’ offices at all hours.

Rihanna and her representatives wanted Totes to do more, however, than merely use her to peddle a product. They wanted Totes to create customized umbrellas featuring sparkly fabrics and glittery charms on the handles — all recommended by the emerging star and her team. Totes also guaranteed the singer a percentage of the sales of the umbrellas.

NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Umbrella went on to become a huge, Grammy-winning hit. And Totes, although it declines to discuss sales data, describes its relationship with Rihanna as “invaluable.” The company, which had never tried such a sweeping design shake-up before, says it now reaches younger shoppers and that traffic on its Web site — which links to Rihanna’s own site — has soared.

AUTHENTIC CONNECTION

“We’ve worked hard to build me and my name up as a brand,” Rihanna says. “We always want to bring an authentic connection to whatever we do. It must be sincere and people have to feel that.”

NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

But where the star ends and the product and pitch begin has grown less and less discernible in the era of the human billboard.

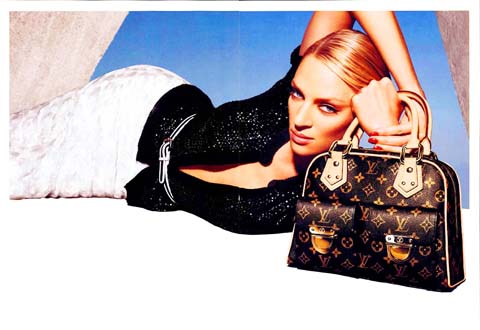

These days, it’s nearly impossible to surf the Internet, open a newspaper or magazine, or watch television without seeing a celebrity selling something, whether it’s umbrellas, soda, cars, phones, medications, cosmetics, jewelry, clothing or even mutual funds.

Nicole Kidman sashays in ads for Chanel No. 5 perfume. Eva Longoria, the bombshellette star of Desperate Housewives, sells L’Oreal Paris hair color. Jessica Simpson struts for a hair extension company, HairUWear, and the acne skin-care line Proactiv Solution. And Jamie Lee Curtis spoons up Dannon Activia yogurt while promoting environmentally friendly Honda cars.

PHOTO: AP

Using celebrities for promotion is hardly new. Film stars in the 1940s posed for cigarette companies, and Bob Hope pitched American Express in the late 1950s. Joe Namath slipped into Hanes pantyhose in the 1970s, and Bill Cosby jiggled for Jell-O for three decades. Sports icons like Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods elevated the practice, often scoring more in endorsement and licensing dollars than from their actual sports earnings.

But over the last decade, corporate brands have increasingly turned to Hollywood celebrities and musicians to sell their products. Stars showed up in nearly 14 percent of ads last year, according to Millward Brown, a marketing research agency. While that number has more than doubled in the last decade, it is off from a peak of 19 percent in 2004. (Hey, it could be more extreme: Celebrities appear in 24 percent of the ads in India and 45 percent in Taiwan.)

Starlets and aging rockers are likely to continue popping up in ads for a very simple reason: Celebrity sells. If consumers believe that a certain star or singer might actually use the product, sales can take off.

“The reality is people want a piece of something they can’t be,” says Eli Portnoy, a branding strategist. “They live vicariously through the products and services that those celebrities are tied to. Years from now, our descendants may look at us and say, ‘God, these were the most gullible people who ever lived.’”

Newer forces are also propping up the celebrity-endorsement boom. Companies, trying to align themselves ever closer to A-list stars (as well as B-listers, C-listers and reality TV pseudocelebrities) and their quicksilver fame are constantly seeking new ways to merge the already-blurry lines between the commercial and entertainment worlds.

Television programmers and music producers are particularly eager to play along as joint marketing deals offer artists new ways to reach audiences while also defraying their own marketing costs. Celebrities have also grown much more sophisticated about the structure and payouts of endorsement deals.

Last fall, the rapper-impresario Sean Combs created a 50-50 joint venture with Diageo, the spirits giant, for Combs to be the brand manager of the Ciroc vodka line. Combs says he made the profit-sharing deal only after refusing to work solely as a pitchman.

“My brand is rocket fuel. It would take this brand 10 years to get to where I can take it in one year,” he says. “I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t want to do just endorsements. I want ownership.”

In the few short years since she exploded onto the music scene, Rihanna, 20, has been involved in about a dozen endorsement and licensing deals. Behind the scenes, her representatives say they vet every offer for two key criteria: how does it support the brand known as Rihanna, and will it help sell more albums?

Rihanna’s commercial for a lip gloss, CoverGirl Wetslicks Fruit Spritzers, opens with outtakes from her steamy Umbrella video, then morphs into a close-up of her wearing the lip gloss before ending with a shot of her album cover — leaving viewers possibly confused whether they just saw an ad for a lip gloss or an album. (Totes, for its part, says it cares not a whit about CoverGirl also capitalizing on Umbrella. The more the merrier, its executives say, because ubiquity benefits everybody in brandland.)

IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH ...

To be sure, marrying a brand to a celebrity has its perils. Just last month, Christian Dior yanked ads from China featuring the actress Sharon Stone after she suggested that the earthquakes that killed tens of thousands of people in China were karmic retribution for the country’s policies toward Tibet.

Yet no less an expert than the comedian Ellen DeGeneres enthusiastically embraces the endorsement whirlwind.

“It’s flattering that companies think of you and they want to work with you,” she says, adding that she is working with American Express because she liked earlier ads the company did with Jerry Seinfeld. The AmEx ads routinely appear first during her talk show.

Although she says she would consider other endorsement deals, she’s not actively looking.

“I would not feel good if I had made a deal and was making money for something that I’m not proud of and don’t have any control over,” she says. “Now watch, cut to next week and I’m endorsing five different things. Look, bread! Isn’t it great? And what goes well with bread? Mayonnaise!”

While Americans face the upcoming second Donald Trump presidency with bright optimism/existential dread in Taiwan there are also varying opinions on what the impact will be here. Regardless of what one thinks of Trump personally and his first administration, US-Taiwan relations blossomed. Relative to the previous Obama administration, arms sales rocketed from US$14 billion during Obama’s eight years to US$18 billion in four years under Trump. High-profile visits by administration officials, bipartisan Congressional delegations, more and higher-level government-to-government direct contacts were all increased under Trump, setting the stage and example for the Biden administration to follow. However, Trump administration secretary

In mid-1949 George Kennan, the famed geopolitical thinker and analyst, wrote a memorandum on US policy towards Taiwan and Penghu, then known as, respectively, Formosa and the Pescadores. In it he argued that Formosa and Pescadores would be lost to the Chine communists in a few years, or even months, because of the deteriorating situation on the islands, defeating the US goal of keeping them out of Communist Chinese hands. Kennan contended that “the only reasonably sure chance of denying Formosa and the Pescadores to the Communists” would be to remove the current Chinese administration, establish a neutral administration and

A “meta” detective series in which a struggling Asian waiter becomes the unlikely hero of a police procedural-style criminal conspiracy, Interior Chinatown satirizes Hollywood’s stereotypical treatment of minorities — while also nodding to the progress the industry has belatedly made. The new show, out on Disney-owned Hulu next Tuesday, is based on the critically adored novel by US author Charles Yu (游朝凱), who is of Taiwanese descent. Yu’s 2020 bestseller delivered a humorous takedown of racism in US society through the adventures of Willis Wu, a Hollywood extra reduced to playing roles like “Background Oriental Male” but who dreams of one day

Burnt-out love-seekers are shunning dating apps in their millions, but the apps are trying to woo them back with a counter offer: If you don’t want a lover, perhaps you just need a friend? The giants of the industry — Bumble and Match, which owns Tinder — have both created apps catering to friendly meetups, joining countless smaller platforms that have already entered the friend zone. Bumble For Friends launched in July last year and by the third quarter of this year had around 730,000 monthly active users, according to figures from market intelligence firm Sensor Tower. Bumble has also acquired the