The symphony of Manhattan Island, composed and performed fortissimo daily by garbage trucks, car speakers, I-beam bolters, bus brakes, warped manhole covers, knocking radiators, people yelling from high windows and the blaring television that now greets you in the back of a taxi, is the kind of music people would pay good money to be able to silence, if only there were a switch.

The other day, in a paint-peeling hangar of a room at the foot of the island, David Byrne, the artist and musician, placed his finger on a switch that did exactly the opposite: it made such music on purpose. The switch was a white key on the bass end of a beat-up Weaver pump organ that was practically the only thing sitting inside the old Great Hall of the Battery Maritime Building, a 99-year-old former ferry terminal at the end of Whitehall Street that has sat mostly dormant for more than a half-century.

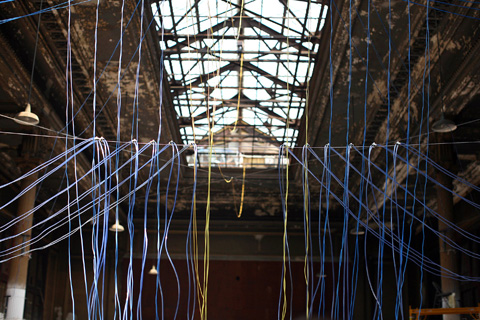

The organ’s innards had been replaced with relays and wires and light blue air hoses. And when the key was pressed, a 110-volt motor strapped to a girder high up in the room’s ceiling began to vibrate, essentially playing the girder and producing a deafening low hum — like one of the tuba tones played by the mother ship in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Or, if you were less charitably inclined, like a truck on Canal Street with a loose muffler. Byrne ran his fingers up the keyboard, causing more hums and whines, moans and plunks and clinks until he came to a key that seemed to do nothing.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

“We’re not getting any register on that bottom one,” he said, sending two artist-technicians up onto a scaffold to figure out why a certain magnetic knocker was not turning one of the room’s giant Corinthian columns into a kind of architectural castanet.

The project Byrne has created with support from the public-art organization Creative Time is a kind of twist on the projects Creative Time has brought into being since it started helping artists use the city as a canvas in 1974. Often the organization finds dilapidated, neglected, historically rich buildings, and artists create installations inside, as the British artist Mike Nelson did last year when he turned a wing of the Essex Street Market on the Lower East Side into a dimly lighted labyrinth. The ferry-terminal project, called, appropriately enough, Playing the Building, opened Saturday.

But in the case of Byrne — a founder of the Talking Heads who has been a visual artist as long as he has been a musician and producer — the Beaux-Arts terminal itself has become the installation, or at least a stunning, 836m² part of it that once served as a soaring waiting room for passengers who came there to board ferries bound for South Brooklyn. The building has been one of those glorious Manhattan antiques caught in a decades-long time warp, not used for major ferry service since 1938. Plans to have it house everything from a children’s museum to a dance troupe to even Creative Time’s offices have fallen through over the years, and now a developer has been chosen to rehabilitate the terminal and build a hotel atop it.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

At least for the next two and a half months, though, the building will simply serve as a gargantuan cast-iron orchestra. Besides being fitted with several motors, which produce the bass sounds by vibrating a set of girders that once supported a stained-glass skylight in the 12m-high ceiling, the organ is attached to a pump that blows air through a tangle of hoses. These hoses snake into the huge room’s old water and heating pipes and conduits, making primitive flute sounds. And then there are more than a dozen spring-loaded solenoids, attached like woodpeckers to the columns and even to a linebacker-size radiator that emits a surprisingly sonorous tone when struck in just the right place with a metal rod.

When you get both hands busy on the keyboard — as anyone who comes to see the work will be allowed to do — the room roars and clatters to life, seeming to harbor an invisible band playing something written by Philip Glass in collaboration with the Stooges, a Japanese sho virtuoso and a kitchen full of 3-year-olds with pots and ladles.

Working on the project recently in his SoHo studio, Byrne said he had generally avoided music-related art projects because he did not want his reputation as a musician to become confused with such work.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

But when he was invited several years ago to propose a piece for Fargfabriken, a gallery space in a former factory in Stockholm, Sweden, he began thinking about how to turn a building into an instrument. (One of his ideas for the Swedish project was to build a huge microwave oven inside the hall.) He had inherited the out-of-tune pump organ from a friend who was moving out of his print studio in the meatpacking district. And so Byrne used the organ to create the first version of Playing the Building in 2005.

Because he generally likes to distance his art from his music, Byrne has not composed pieces for the building-organ and does not plan to play it publicly. But he said he hoped the project would say something about the direction of popular music.

“I’m not suggesting people abandon musical instruments and start playing their cars and apartments, but I do think the reign of music as a commodity made only by professionals might be winding down,” he said. “The imminent demise of the large record companies as gatekeepers of the world’s popular music is a good thing, for the most part.”

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the