Thirteen years on, it is easy to forget just how much of a phenomenon Alanis Morissette’s first major album, Jagged Little Pill, proved to be — particularly among women. With its immortal lyric, “D’you still think of me when you fuck her?” ringing around the bedrooms of angst-ridden teenagers (and often those of their mothers too), the album became the second-biggest seller of the 1990s. It was assumed that Morissette would go on to write more pithy, angry songs about relationships — instead, she took 18 months off to travel around India with her friends, and returned to record music that even she, at times, has called “amazingly self-indulgent.”

So it is good to see the return of some of that early anger on her new album, Flavors of Entanglement. While writing it, she split up with her longtime fiance, the Canadian actor Ryan Reynolds, an aspiring A-lister who is now engaged to Scarlett Johansson. She says that “this album was like a life raft ... . I wanted my own personal story to unfold as it was happening.” As such, it is effectively a breakup album, moving from fury to hedonist escape to hope, and featuring some fantastically barbed lyrics. On the grinding, juddering track Straitjacket, for instance, she castigates her ex-lover, “I don’t know who you are, talking to me with such fucking disrespect,” while on Underneath she sings, “Look at us break our bonds in this kitchen/Look at us rallying our defenses/Look at us waging war in our bedroom.” It is a raw evocation of the loss of someone she had expected to build a life with.

We meet in a hotel in London, and, at 33, Morissette looks rounder and more beautiful than the tomboy I first interviewed back in 1996. On her fifth major album, she feels that she has come full circle. “What’s that line from T.S. Eliot? To arrive at the place where you started, but to know it for the first time. I’m able to write about a breakup from a different place. Same brokenness. Same rock-bottom. But a little more informed, now I’m older. Thank God for growing up,” she adds.

PHOTO: EPA

Morissette is more approachable than most well-known artists, and laughingly admits that she has a problem “setting boundaries.” When young women come up to her, as they regularly do, wanting to tell their stories about suicide attempts, divorce, body image and parental death, she can’t bring herself to back away.

It is partly this that has inspired her other current project, a memoir focusing on women’s issues. She is halfway through writing it, and has chapters on themes such as sexuality, beauty, relationships and work. Those themes underline the fact that for years Morissette has struggled with low self-esteem. Growing up in “a chauvinistic, patriarchal environment” in Ontario, with her Hungarian/French-Canadian family, she was an established actor and pop star from an early age, and spent the late 1980s singing bland dance pop from beneath a frosted fringe, feeling as if she was “14 going on 40.” In fact, the pressure was so great that at 16 she became anorexic and bulimic.

One day, a record executive summoned her to the studio and “suggested I was getting too fat, saying, ‘You need to go on a diet.’ My response was, ‘But I’m a singer.’ He said, ‘Yes, well, you need to get small again.’ That started a whole cycle. Two days later I was sticking my fingers down my throat.”

PHOTO: EPA

She feels that the pressure and obsession with body image is one of the key issues facing women today. “Europe seems a little softer,” she says, “but in America it’s harsh. In LA, where I live, it’s all about perfectionism. Beauty is now defined by your bones sticking out of your decolletage. For that to be the standard is really perilous for women.”

Does she see herself as a feminist? “What’s your definition?” she asks. Equal pay. Equal rights. That women should be able to fulfill their potential regardless of gender. “If that’s what the definition is, then yes, absolutely ... . Women are so powerful they’re scary, and the incentive to squash this has been going on for so long that some of us actually believe we’re subordinate.”

Morissette was 19 when she left Ontario and gave up trying to be “Miss Perfect.” She ended up in Los Angeles, working with rock producer Glen Ballard, who encouraged her to free-associate, and to bring out her unfettered, unruly side in her lyrics. Madonna signed her up to her Maverick label, and Jagged Little Pill followed.

Although passion coursed through the record, Morissette has been accused, repeatedly, of being a puppet for male producers. Her response was to “over-function,” to micromanage each video and record, and to produce herself.

“Now I see the futility in that,” she says. “I’m still empowered, but it’s lovely to let the producer or director work without trying to control the whole situation.” Tori Amos recently suggested that it is almost impossible to have real independence as a female artist on a major label — “You’re accepted up until the point you want to be your own producer and have your own label, and then things close down,” she said — and Morissette agrees that executives often balk at her independence. “It’s such a common, daily thing I don’t even notice it any more,” she says. “It’s scary for them, especially if there’s money involved. I’m a liability to them — I’m a woman, I’m empowered, I’m an artist. I’ve had executives who can’t come to my shows they’re so scared of me. I’ve been a thorn in many people’s sides just by existing.”

Did going to India make her lose her rage? “No. I felt gratitude. Humility. My rage showed up in other ways. I’m always fascinated by how people’s rage shows up. Canada has a passive-aggressive culture, with a lot of sarcasm and righteousness. That went with my weird messianic complex. The ego is a fascinating monster. I was taught from a young age that I had to serve, so that turned into me thinking I had to save the planet.”

This was reflected in the role she played in Kevin Smith’s 1999 comedy, Dogma, a satire on the Catholic church: Morissette was cast as God. Now she doesn’t feel the need to save the world, or be approved of. “I highly recommend getting older! There’s less tendency to people-please.” Just one look at My Humps, the spoof video she put up on YouTube last year as a retort to the rap act Black Eyed Peas shows how relaxed and confident she has become. In the video, she ridicules the notion of women as doe-eyed sexual decorations, turning the tables with her comic domination of some male backing dancers.

Does she think the industry has become easier for female stars in recent years, or has the intrusive tabloid focus on the public breakdowns of Britney Spears and Amy Winehouse, for instance, made it harder?

“In terms of exposure, there’s never been a better time,” she says. “You can throw things up on YouTube, and release music via the Internet. But fame is tough to navigate when your relationship with yourself is still healing, and the rupture is festering and bleeding in public. I feel compassionate towards women like Britney and Amy. But they’re big girls. They’ll get through it. And they wanted it to a certain extent. This fame thing is something you can stay out of if you want to.”

Morissette recognizes that in the fickle world of pop, an artist’s strongest asset is her music — songs that will move people long after the image fades. “That’s what I keep coming back to. Is what you’re writing who you are, what you really want to be doing?” she says. “That’s all that matters.”

In 2020, a labor attache from the Philippines in Taipei sent a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanding that a Filipina worker accused of “cyber-libel” against then-president Rodrigo Duterte be deported. A press release from the Philippines office from the attache accused the woman of “using several social media accounts” to “discredit and malign the President and destabilize the government.” The attache also claimed that the woman had broken Taiwan’s laws. The government responded that she had broken no laws, and that all foreign workers were treated the same as Taiwan citizens and that “their rights are protected,

A white horse stark against a black beach. A family pushes a car through floodwaters in Chiayi County. People play on a beach in Pingtung County, as a nuclear power plant looms in the background. These are just some of the powerful images on display as part of Shen Chao-liang’s (沈昭良) Drifting (Overture) exhibition, currently on display at AKI Gallery in Taipei. For the first time in Shen’s decorated career, his photography seeks to speak to broader, multi-layered issues within the fabric of Taiwanese society. The photographs look towards history, national identity, ecological changes and more to create a collection of images

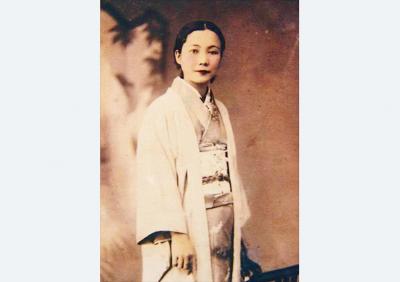

March 16 to March 22 In just a year, Liu Ching-hsiang (劉清香) went from Taiwanese opera performer to arguably Taiwan’s first pop superstar, pumping out hits that captivated the Japanese colony under the moniker Chun-chun (純純). Last week’s Taiwan in Time explored how the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) theme song for the Chinese silent movie The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記) unexpectedly became the first smash hit after the film’s Taipei premiere in March 1932, in part due to aggressive promotion on the streets. Seeing an opportunity, Columbia Records’ (affiliated with the US entity) Taiwan director Shojiro Kashino asked Liu, who had

The recent decline in average room rates is undoubtedly bad news for Taiwan’s hoteliers and homestay operators, but this downturn shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. According to statistics published by the Tourism Administration (TA) on March 3, the average cost of a one-night stay in a hotel last year was NT$2,960, down 1.17 percent compared to 2023. (At more than three quarters of Taiwan’s hotels, the average room rate is even lower, because high-end properties charging NT$10,000-plus skew the data.) Homestay guests paid an average of NT$2,405, a 4.15-percent drop year on year. The countrywide hotel occupancy rate fell from