The two passions of TC Yang’s (楊祖珺) life — music and political activism — went hand-in-hand during a time of major change in Taiwan.

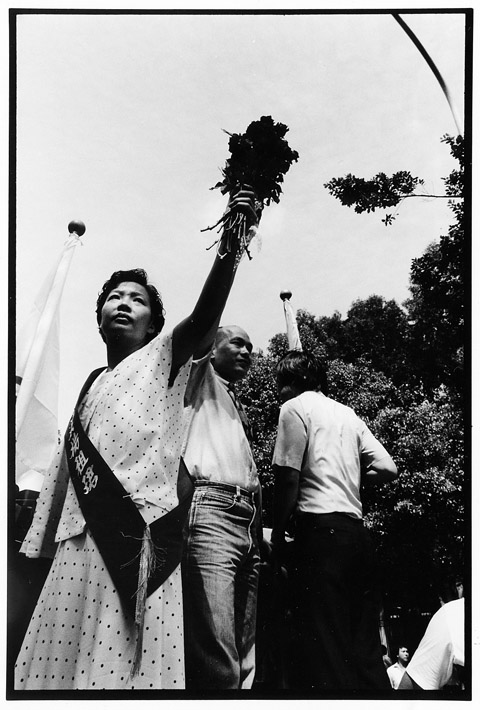

It was November 1986 and bold protests to lift martial law, which had been in effect since 1949, were in full swing.

Yang and a handful of protestors stood on Boai Road (博愛路) in Taipei outside the Taiwan Garrison Command (警備總部), the military unit that enforced martial law.

PHOTO: HSIEH SAN-TAI; COURTESY OF TC YANG AND TREES MUSIC AND AR

Facing a line of 30 soldiers standing guard, Yang yelled through a megaphone: “The Garrison Command has been a malignant tumor in our society!”

Then a battle ensued — a battle of song. Yang sang Flood of Passion (熱血滔滔), a Chinese anti-war tune from the 1930s. The soldiers sang back Help Our Own Country (自己的國家自己救).

“We even heard soldiers from inside the [Garrison Command] building singing,” Yang chuckled in her raspy voice, during an interview last week.

PHOTO: LIANG CHENG-CHU; COURTESY OF TC YANG AND TREES MUSIC AND

Martial law was lifted in 1987, and the dangwai (outside the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party, KMT) movement gained momentum, paving the way for Taiwan’s first opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). As Yang became more deeply involved in the movement, “there was no time to sing.” By the 1990s, she had given up music.

But now Yang, a professor of culture studies at Chinese Cultural University, is in the process of “recovery.” She is revisiting her music with a new compilation CD, A Voice That Could Not Be Silenced, which was released in February. The album is a retrospective of songs from the 1970s and 1980s that trace Yang’s path from singer to activist. She is on a lecture tour for the album that ends this month.

The relationship between music and politics is “very natural,” says Yang, dragging on a cigarette.

PHOTO: LEE WEI-I; COURTESY OF TREES MUSIC AND ART

“People say I’m an activist, I started a social movement. But I didn’t aim [to start a] social movement. I was just doing what I thought should be done.”

Yang was already known as a talented folk singer in her first year at Tamkang University in the mid-1970s. An avid record collector, her main inspiration came from Joan Baez. “Hearing her, I decided that when you sing, it’s got to be like that!”

But it wasn’t Baez or Bob Dylan — also popular at the time — that set Yang’s music on a political trajectory. It was Li Shuang-ze (李雙澤), a singer and fellow student at Tamkang. Li caused a stir in Taiwan’s nascent folk scene: tired of hearing English songs, he started to write and sing in Mandarin and Hoklo.

PHOTO: TSAI MING-DE; COURTESY OF TC YANG AND TREES MUSIC AND ART

Two of Li’s songs, Formosa and Young China, became signature songs for Yang and her friend, Paiwan Aboriginal singer Kimbo Hu (胡德夫). To the KMT, the songs were “pro-Taiwan independence” and “pro-unification with communist China.” To Yang, the songs were an awakening: “My ‘China’ was right under my feet, my ‘Taiwan,’ my beautiful island, was right under my feet.”

“Those songs made me feel alive,” she said.

Yang became determined to spread Li’s music after his unexpected death in 1977: “It was like I was on a mission … it was something I had to do.” Li had inspired Yang and Hu to start the Sing Our Own Songs movement (唱自己的歌), which placed them at the forefront of the Taiwanese folk music scene.

Yang’s musical “mission” put her on a crash course with the repressive elements of the KMT regime. After graduating, she recorded a popular album, and became the host of a television program on folk music. But Yang quickly became frustrated: a third of the songs on the show had to be government-approved. And she was forbidden to sing Li Shuang-ze’s songs on air.

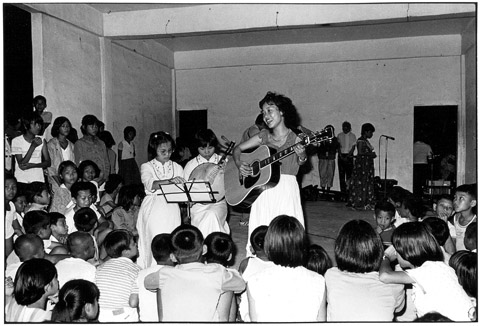

She quit after nine months and went to work at the Guangci Care Home (廣慈博愛院), a halfway house for teenage prostitutes. Yang held a charity concert to raise awareness for the home, which irked the KMT: they labeled her as a person with “problematic thinking” and ostracized her for “exposing the dark side of society.”

The charity concert set Yang on her path as a political activist. She started performing at factories and labor rallies. The KMT followed, banning her from public performances between 1979 and 1981. But Yang continued to record her songs as anthems for the dangwai movement, which included her husband at the time, former legislator Lin Cheng-chieh (林正杰).

By the late 1980s, Yang wasn’t singing much. Most of her time went to running a social issues magazine, Progress (前進) and helping Lin, a frequent political target of the KMT. As the dangwai movement grew, their marriage fell apart. Yang returned to school, earning her PhD in cultural studies from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Her departure from music remains painful. “I left something that was so important to me, something I loved so much … I could live without the social movement, my degree … but music … ,” Yang said, tears welling in her eyes.

At first, she was reluctant about releasing the new album, but relented after encouragement from friends: Chung She-fong (鍾適芳), whose label, Trees Music and Art, produced the album; and a friend from the dangwai movement, Tsai Shih-yuan (蔡式淵).

On a lecture tour to promote the album, Yang hadn’t planned on singing. But she had trouble sparking the interest of a new generation of students. So she started to bring her guitar to the lectures, which has helped. “I still feel a little embarrassed to do my songs, though,” she said.

Yang has started to write songs again, and she still recalls the thrill of when she started performing: “As soon as I started to sing, I was not the least bit worried about the world. I dived right into the song.”

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern