Marina Silva will never forget the day the bulldozers rolled up on her family’s doorstep. It was the beginning of the 1970s and in the isolated Amazon community of Bagaco, where she was born, Silva, then about 12, looked on curiously as work began on a major highway to link the Brazilian rainforest with the rest of the country. Shortly afterwards, her relatives began to die. First two younger sisters, then her uncle and finally her cousin: all victims of a malaria epidemic imported by the road builders.

“I don’t know if I was conscious that the road was bringing all that, but it made me write on my own flesh the consequences of what it meant to mess around with nature without giving the slightest attention to the need to look after it,” she remembers.

Fast-forward to January 2003. Following the historic election of Brazil’s first working-class president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Silva was named environment minister, thrusting this former rubber tapper on to the front line of Brazil’s battle against deforestation — and of the fight against climate change.

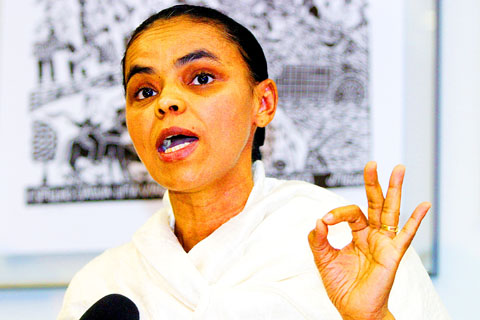

PHOTO: AP

On May 13, however, the fairytale came to an abrupt end. After just over five years as environment minister, Silva resigned. In her short resignation letter, she cited “the growing resistance found by our team in important sectors of the government and society.”

“It’s time to start praying [for the rainforest],” said Sergio Leitao, director of public policy for Greenpeace in Brazil, claiming the government had “now made it clear that the idea of development at any cost is what will win out.”

A week after her resignation, a weary-looking Silva, 50, is unable to pinpoint a single cause for her decision. She is officially between jobs (she will return to her seat in the senate at the end of the month), but in her apartment in Brasilia, surrounded by half a dozen giant, multicolored orchids sent by well-wishers, she looks as busy as ever. She is careful not to name names but leaves little doubt as to why she abandoned the government of Lula, a longtime friend and ally from Brazil’s Workers Party.

PHOTO: AP

“I realized that I was no longer in a position to stabilize what had already been achieved and to carry on expanding these achievements,” she says. Seven days after resigning, she has still not seen the president, whom she has known for 30 years.

Silva’s resignation is the story of a conflict between two Brazils. In one corner are the farmers, businessmen and ordinary Brazilians who see the country’s natural resources as a route to economic success. In the other are the environmental activists, indigenous groups and concerned spectators who believe that Brazil’s march to economic greatness will mean the continued devastation of its rainforest. Silva attempted to tread a path between the two, trumpeting sustainable development. This, she said, would provide better living conditions for the 25 million people in the Amazon region without obliterating the rainforest.

But walking this tightrope was never going to be simple, even for the notoriously resilient Silva, who frequently cites Nelson Mandela as one of her inspirations.

Maria Osmarina da Silva was born in 1958 in a community of rubber tappers called Seringal Bagaco, deep in the western state of Acre. The nickname Marina stuck immediately. One of 11 children (three later died), she was orphaned at 16 and moved to the state capital, where she received a Catholic education and worked as a household maid.

Heavily influenced by liberation theology, she graduated in history from Acre’s Federal University at 26 and became increasingly politically active. In 1984 she helped create Acre’s first workers’ union.

From an early age Silva was considered a guerreira, a battler, overcoming numerous episodes of tropical diseases such as malaria, and later mercury poisoning. At 35, she was elected as the youngest female senator in Brazil’s history. She became a household name, famous for her shrill but powerful voice and unflinching defense of the Amazon. When Lula da Silva was piecing together his first cabinet, her name was reportedly at the top of his list.

It was a crucial moment: between 2001 and 2002, 26,000km² of rainforest had been lost. Illegal logging was spiraling out of control. A 40-year assault, led by loggers, ranchers and soy farmers had destroyed 20 percent of the Brazilian Amazon.

Last August, however, the government celebrated a 30 percent drop in rainforest destruction between 2006 and 2007 — the result, it said, of a plan launched in 2004, though many argued that the drop owed more to a fall in global commodity prices.

But the fault lines between Silva and other sectors of the government were becoming increasingly clear, most strikingly in relation to an economic plan unveiled in 2007. Designed to propel Brazil towards the same level of growth as Russia, India and China, it proposed constricting two massive hydroelectric dams in the Amazon. Activists claim the dams will displace thousands of people.

In January of this year, the tensions grew, following the release of satellite images, produced by the government, which showed a sudden spike in deforestation. Silva called a press conference, at which she blamed the destruction in part on soy farmers clearing more land for their crops. Her comments are reported to have infuriated Lula. Silva described the rise in deforestation as a “cancer;” Lula rebutted that it was an “itch,” at most a “little tumor.” It was becoming obvious that something had to give. Last week, in a move widely seen as a snub to Silva, Lula placed Mangabeira Unger, known for his controversial ideas on development and industrialization, in control of a new sustainable development scheme for the Amazon. Simultaneously, several Amazonian politicians, among them Blairo Maggi, one of the world’s leading soy producers, mounted a lobby to overthrow measures that banned banks from lending money to fund projects in areas of illegal deforestation.

“This was the last straw,” says Sergio Leitao of Greenpeace. “How many times was she forced to back down? She didn’t want to be responsible for this and so she said: ‘Not on my watch.’”

Still, Silva is upbeat. She talks of an awakening in Brazil and around the world, “a new political pact with society that wants Brazil to develop but with the preservation of the Amazon, the Atlantic rainforest, the savannah and of all our water reserves.” She is also adamant that this engagement has enabled a crackdown on the illegal loggers.

“Without the support of society it would have been impossible to have put 600 people involved in environmental crimes in the Amazon in jail,” she says. “This is something that is achieved by a new social pact that is appearing inside and outside of the country.”

While supporters have described her exit from power as a defeat for the green cause, she insists that progress is being made. “Today we are living through the challenge of prevention, of looking twice before doing something, discussing twice before doing something. Because each thing that we alter can lead to ... dramatic consequences. Those who celebrated the industrial revolution never thought that we were injuring the planet, almost fatally. We didn’t have this knowledge. Today we know.”

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them