Any writer who has struggled to “do the words” would take heart from the self-effacing assessment written for himself by Ian Fleming, the raffish Englishman born 100 years ago this month who became one of the most successful authors of his time through the creation of the world’s best-loved spy, James Bond.

Fleming died in 1964, at 56, of complications from pleurisy after playing a round of golf in Oxfordshire though he had a heavy cold. But the real culprits were years of smoking up to 80 cigarettes a day, and a fondness for drink. Perhaps because of the difficulty he found in resisting life’s indulgences, he adopted a strict writing routine in his last 12 years, the period in which he wrote more than a dozen Bond novels that spawned the multibillion-dollar film franchise.

Rising early for a swim in the aquamarine waters in the cove below his idyllic Jamaican retreat, Goldeneye, Fleming tapped away at his Remington portable typewriter with six fingers for three hours in the morning and an hour in the afternoon — 2,000 words a day, a completed novel in two months, all the while keeping up the sybaritic lifestyle that led Noel Coward, a frequent guest at Goldeneye and no puritan himself, to describe the Fleming household as “golden ear, nose and throat.”

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Fleming, who saw 40 million copies of his books sold in his lifetime but died before the Bond franchise went stratospheric, had no literary pretensions. He described his first Bond book, Casino Royale, as “an oafish opus,” and offered further disparagement in a 1963 BBC radio interview. “If I wait for the genius to come, it just doesn’t arrive,” he said. Asked if Bond had kept him from more serious writing, of the kind achieved by his older brother, Peter, a renowned explorer and travel writer, he replied: “I’m not in the Shakespeare stakes. I have no ambition.”

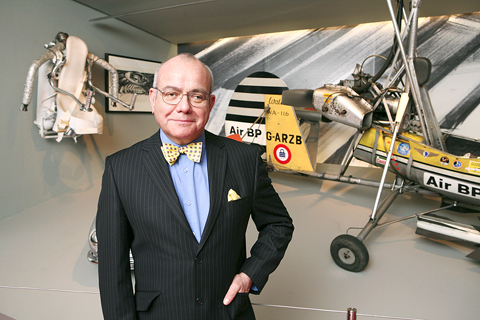

Fleming’s workaday approach to writing is among the revelations drawing crowds of Bond lovers to For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond, an exhibition that opened at the Imperial War Museum in London last month and runs through March 2009. For the museum, founded in 1917 and guarded by two 18-inch guns from a World War I dreadnought, there is something — well, raffish — in the staging of an exhibition about the glamorous, gadget-wielding, womanizing, devil-may-care Bond and his creator, for whom the superspy was in many respects an alter ego.

The museum’s former curator, Alan Borg, whose 13-year tenure as director ended in 1995, encouraged innovative approaches by reminding his staff that “the three most off-putting words in the English language” were encompassed by the museum’s name.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

“And we have to fight against that,” said Terry Charman, the museum’s senior historian and curator of the Bond exhibition.

The display explores the relationship between Fleming and Bond, examining how much of the fictional spy is built on the author’s character — the degree to which Bond was his “fantasy version of himself,” as Charman put it. As well, it shows how Fleming drew on his experiences as a man about town and as a prewar foreign correspondent, in the world of banking and investment, and as a World War II aide to the head of the UK’s directorate of naval intelligence, to give what he described as “verisimilitude” to Bond’s world of spies and villains and romance.

Of his Bond plots, Fleming, ever prosaic about his talent, said, “I extracted them from my wartime memories, dolled them up, attached a hero and a villain, and there was the book.” For M, Bond’s irascible, domineering secret service overseer, he had as a model Rear Admiral John Godfrey, his wartime intelligence chief; old school friends, golfing partners and girlfriends also metamorphosed into Bond characters. Even his villains had real-life antecedents.

Bond himself, Fleming said, was “a compound of all the secret agents and commandos I met during the war,” but his tastes — in blondes, martinis “shaken, not stirred,” expensively tailored suits, scrambled eggs, short-sleeved shirts and Rolex watches — were Fleming’s own. But not all the comparisons were ones the author liked to encourage. Bond, he said, had “more guts than I have” as well as being “more handsome.” And he was eager to discourage the idea that he had been as much of a Lothario as Bond before his marriage to Ann Rothermere, whom he wed in 1952, the year he wrote Casino Royale.

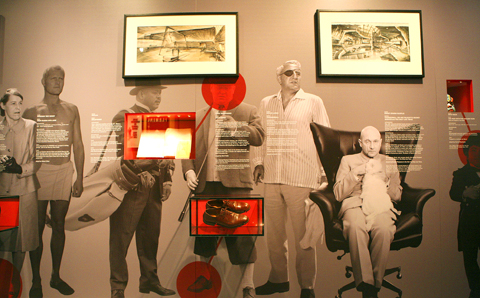

But the exhibition suggests otherwise. A section of the show titled Friends and Lovers has one of a stable of prewar girlfriends, Mary Pakenham, saying of Fleming, “No one I know had sex so much on the brain as Ian.”

Nov. 11 to Nov. 17 People may call Taipei a “living hell for pedestrians,” but back in the 1960s and 1970s, citizens were even discouraged from crossing major roads on foot. And there weren’t crosswalks or pedestrian signals at busy intersections. A 1978 editorial in the China Times (中國時報) reflected the government’s car-centric attitude: “Pedestrians too often risk their lives to compete with vehicles over road use instead of using an overpass. If they get hit by a car, who can they blame?” Taipei’s car traffic was growing exponentially during the 1960s, and along with it the frequency of accidents. The policy

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest

While Americans face the upcoming second Donald Trump presidency with bright optimism/existential dread in Taiwan there are also varying opinions on what the impact will be here. Regardless of what one thinks of Trump personally and his first administration, US-Taiwan relations blossomed. Relative to the previous Obama administration, arms sales rocketed from US$14 billion during Obama’s eight years to US$18 billion in four years under Trump. High-profile visits by administration officials, bipartisan Congressional delegations, more and higher-level government-to-government direct contacts were all increased under Trump, setting the stage and example for the Biden administration to follow. However, Trump administration secretary

The room glows vibrant pink, the floor flooded with hundreds of tiny pink marbles. As I approach the two chairs and a plush baroque sofa of matching fuchsia, what at first appears to be a scene of domestic bliss reveals itself to be anything but as gnarled metal nails and sharp spikes protrude from the cushions. An eerie cutout of a woman recoils into the armrest. This mixed-media installation captures generations of female anguish in Yun Suknam’s native South Korea, reflecting her observations and lived experience of the subjugated and serviceable housewife. The marbles are the mother’s sweat and tears,