So what do you do if you’re watching an absolute stinker of a film and tomorrow you are interviewing its star?

Lucky me. I’ve got an advance copy of the new Woody Allen film, Cassandra’s Dream, so I invite friends around for tea and a private screening. We’re all Woody fans, and as usual there is a starry cast, this time including Ewan McGregor and Colin Farrell. We turn down the lights, and sit back in expectation.

And it is an absolute shocker. One of the worst films I’ve ever seen. This was supposed to be a treat, and I feel embarrassed that I’ve made people sit through it. The lights come up, and nobody knows what to say.

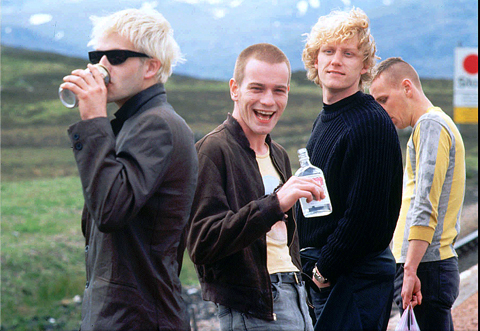

PHOTO: AP

Cassandra’s Dream is set in London, but for all Allen’s understanding of London and the nuances of Londoners’ language, it might as well have been Mars. In the film, McGregor and his brother, played by Farrell, find a way out of their financial problems by becoming hit men. The characters are toilet-paper thin, the story ridiculous, the coincidences and portentous allusions to Greek tragedy even more so.

Unfortunately, I’m interviewing McGregor the next day. As my friends leave, one by one they ask if I’ll tell him what we thought about the film. I tell them it would be dishonest not to, but I’ll try to be tactful.

McGregor shakes my hand firmly. He’s dressed in black, blessed with lovely teeth, and a handsome, laddish face. He doesn’t appear to have aged since he made his name in the Danny Boyle films Shallow Grave and Trainspotting. He just looks cooler, more sophisticated.

PHOTO: EPA

McGregor was born in 1971, in Crieff, Scotland, to teacher parents. He moved to London to study at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1988 and was six months short of graduation when he was given his first television role in Dennis Potter’s Lipstick on Your Collar. He made a wonderful start to his movie career: within a year of Trainspotting, he was stripped and covered in Japanese calligraphy for Peter Greenaway’s erotic love story The Pillow Book, and headed up a poignant story about the last days of a colliery band in Brassed Off. McGregor seemed an adventurous actor, keen to stretch himself with both populist and arthouse movies.

At the end of the 1990s, he won the part of Obi-Wan Kenobi in the Star Wars prequel series and since then there have been any number of forgettable movies — Rogue Trader, Eye of the Beholder, The Island. Still, he became even more famous as a motorcycle adventurist in two TV series with his friend Charley Boorman: The Long Way Down and The Long Way Round. The motorbike adventures made for successful TV and books. In The Long Way Round, he and Boorman traveled more than 30,500km from London to New York via Europe and Asia, and then in The Long Way Down they went more than 8,000km from John O’Groats, on the northern tip of the Scottish mainland, to South Africa. One episode began, perhaps ironically, “apart from two trucks and a camera crew, we’re on our own.”

Would McGregor prefer to have done it without a camera crew? “The actual crew don’t get in the way because we just travel with our mate Claudio [cameraman Claudio von Planta], just the three of us, and we just meet the other crew every now and again. I never felt it got in the way. I do trips on my own, but I’ve never done one as long as that on my own. But I will do one day, I’m sure of it.”

He is convinced the trips will help his acting because of the exposure to new experiences. “Acting is only about real life if you’re representing real people in real situations, so by going out and seeing it, as opposed to just being on movie sets all the time.” You can get removed from real life on movie sets? “Yeah, I suppose. But I don’t do the trips because I want to escape life on the film sets. It’s not the case for me at all, I’m very happy being an actor.”

But filmwise there has been little for McGregor to be proud of this side of the millennium. There has been the occasional gem — notably Young Adam (2003), a bleak tale in which McGregor plays an amoral drifter. But watching the Woody Allen film, I can’t help feel his movie career has stunted or even regressed — at 37, he’s still playing the twentysomething cheeky-chappy with little going on upstairs.

When we meet, he’s only just completed his run as Iago in Othello at the tiny Donmar Warehouse theatre in London, and he’s raving about it. He says it’s been a great experience, an incredible journey, the toughest thing he’s done.

As he talks about Iago, you sense he has still not got his head round just how nasty the Shakespearean villain is. “He’s despicable.” Playing Iago has made him think more about the process of acting because Iago himself is a such a consummate actor. “Only when he’s on stage alone does he tell the truth. It was bit of a headfuck to begin with.”

As we talk, I’m aware of a stonking big elephant in the room — the Allen film. I know I have to bring it up, but I want to do so politely. “So what was it like to star in the worst movie ever made?” I don’t ask. “So what was it like working with Allen?” I do ask. Great, he says, wonderful, another rewarding journey. “You go and meet him in New York for 15 seconds. He says he just wants to meet you in the flesh and then he sends you the script, which I read and loved. I loved the story, I think the story is fantastic — it’s a strong, powerful story of normal guys faced with a huge drama. I liked it very much.” Blimey. I think he means it.

Where does Allen rate among the directors he’s worked with? “I’d work with him every time if I could. Loved him to bits. I love the way you have to raise your game for him. He only likes three or four takes and you really have to nail it, so I found myself working very hard, particularly on the very long scenes.” All the time he’s talking, I want to shout out: “But Ewan, don’t be daft, you didn’t nail it because there was nothing there to nail. The guy has lost it.”

“It is very tightly written,” he continues. “But he says before you start shooting any scene: ‘Remember these are just words that I wrote. Say whatever you like.’” So there’s scope for improvisation? “Completely. Except you wouldn’t want to change any of his words. Because it’s so well written you wouldn’t want to change a line.”

I’m trying to control myself, but finding it increasingly difficult. I finally tell him I don’t like the film. He asks why not, and I don’t know where to start. Well, I say, don’t you feel it’s alien from his normal territory? “Not at all, because I don’t know what his normal territory is — because he does a film like Scoop and some comedies but then he also does film that are really hard, like Crimes and Misdemeanors — that’s about hiring a hitman isn’t it?”

Yes, but that was set in New York, which he understands. He hasn’t got a clue about London and the dialogue is just awful. “Right, right, right,” McGregor says diplomatically, but very probably meaning “Wrong, wrong, wrong.” I apologize for being so forthright, but tell him I can’t help myself, I’m a passionate man. “I don’t feel like that about it at all. I think it’s a cracking story, in the same way that Match Point was a great story. I’m not going to disagree with you, because that’s the way you saw it, but I didn’t have a problem with it.”

At the end of the movie, I tell him, we had to rewind to the opening credits to make sure it really was a Woody Allen film and that we hadn’t been taken for a ride. “Right, right, right,” he says again, like a psychiatrist listening to a particularly disturbed patient. I say it’s not your fault — it was the direction and the script. “Is it because of the dialogue? Or the heaviness of the film? Or the tragedy of the film?” No, I say, it’s because it seems like a terrible stage production of a terrible film that never belonged to a time or place.

Oops. Time to change the subject. I ask about his family — McGregor has been married for 13 years to the French production designer Eve Mavrakis, and they have three daughters. In 2006, following the first motorcycle journey, they adopted a four-year-old Mongolian girl Jamiyan. That must have been a life-changing trip, I say.

“I won’t discuss that with you, so you could ask me another question.” Why won’t he discuss it? “I’ve never discussed it with a journalist and I’m not about to change that.”

Fair enough, but he could handle it a little more elegantly. After all it is hardly the most intrusive question in the world; he has agreed to be interviewed and how hard would it have been to say, “Yes, she has brought us much joy but I’d prefer not to talk about her.”

So we return to the subject of his work. What’s his favorite of the films he’s made? “I don’t have a favorite really. I feel that they’re all stepping stones from one to the next.”

I tell him that he was once described as a “promiscuous” actor — he has taken so many roles, at times with scant regard for their quality. Does he look back on some of the films, and think they were rubbish? “No. Because I don’t ... . Some of them just don’t work, some of them I’m not very good in, some the films aren’t very good.”

That’s honest of you, I say. So which films do you think you are good in and which are you not so good? “No, I wouldn’t.” Go on! “No, I’m not going to,” Pleeeease! “No, no, no ... . It doesn’t matter if they’re not successful at the box office. It’s nice if people see them but it’s not the be all and end all for me.”

His publicist pops her head round the corner. He looks relieved. “Five minutes,” he says. “That’s the five-minute call.”

At one point McGregor tells me, “I don’t do things lightly, I don’t take a job then just phone it in, I’ve never done that.” But that is just what it feels as if he’s done in this interview — phoned in a performance. As we wind up, he tells me why he loves acting. “I think it’s valid, I like it, I think there’s great depth to it in terms of looking at the world, looking into people’s lives, trying to get to the bottom of what people do and why they do things.” And as he’s talking, I’m wondering how on earth I’m supposed to get to the bottom of McGregor when he is prepared to reveal so little of himself. But in a strange way, I think, perhaps he has shown more than he intended to.

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

There is a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) plot to put millions at the mercy of the CCP using just released AI technology. This isn’t being overly dramatic. The speed at which AI is improving is exponential as AI improves itself, and we are unprepared for this because we have never experienced anything like this before. For example, a few months ago music videos made on home computers began appearing with AI-generated people and scenes in them that were pretty impressive, but the people would sprout extra arms and fingers, food would inexplicably fly off plates into mouths and text on

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

US President Donald Trump’s threat of tariffs on semiconductor chips has complicated Taiwan’s bid to remain a global powerhouse in the critical sector and stay onside with key backer Washington, analysts said. Since taking office last month, Trump has warned of sweeping tariffs against some of his country’s biggest trade partners to push companies to shift manufacturing to the US and reduce its huge trade deficit. The latest levies announced last week include a 25 percent, or higher, tax on imported chips, which are used in everything from smartphones to missiles. Taiwan produces more than half of the world’s chips and nearly all