On a recent visit to Cambodia, outside a children’s hospital a block from my hotel, I saw a large red-and-white sign that warned of a severe epidemic of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Years ago, the disease killed our tour guide’s 5-year-old brother.

My tripmates and I managed to escape even the milder form of this mosquito-borne viral infection — we all slept in an air-conditioned hotel and each day applied insect repellent with 30 percent DEET on our exposed skin. But I have since learned that I could have been infected on several previous trips abroad and even in parts of the US.

Dengue (pronounced DEN-gee) fever has increased rapidly in tropicaal and subtropical areas worldwide in recent years, thanks to factors both natural and manmade.

Among the countries that have experienced recent epidemics are Cambodia, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. In the Western Hemisphere, outbreaks have also occurred in some Caribbean islands, Cuba, northern Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Puerto Rico and Venezuela.

This year, dengue fever has ravaged Rio de Janeiro, infecting more than 75,000 people in Brazil’s Rio state, including Diego Hypolito, a world champion gymnast and gold-medal favorite in the Beijing Olympics this summer. More than 80 people in Rio have died from dengue.

Though most North Americans who receive a diagnosis of dengue fever were infected while traveling to countries where the disease is endemic, including Mexico, it has also struck residents of Hawaii and Texas who had not left US shores. And last summer a related mosquito-borne disease, chikungunya, afflicted more than 100 residents of a village in Italy, Castiglione di Cervia.

The disease is not contagious; rather, it is passed from person to person through the bite of a virus-carrying mosquito.

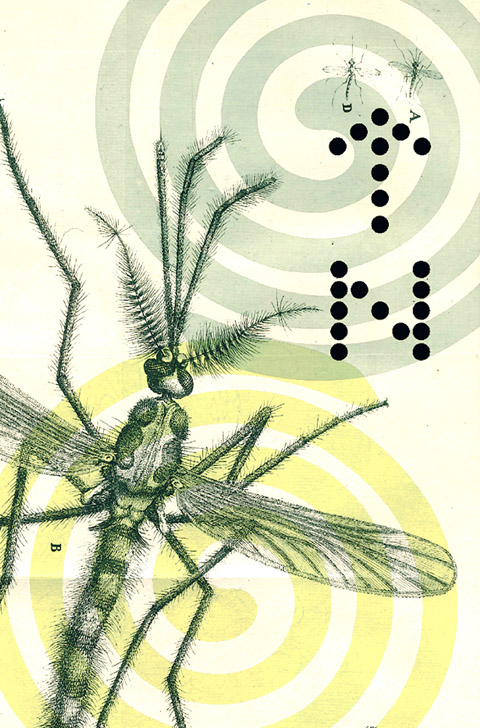

Epidemiologists say that global warming is allowing the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, a vector of both chikungunya and dengue fever, to survive in areas that were once too cold for it. This mosquito now thrives across southern Europe and even in France and Switzerland. All it takes is one infected traveler to bring the dengue virus home, where the bite of a resident tiger mosquito could transmit it to others.

The primary vector for dengue fever is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biter that is especially active during the early morning and late afternoon. (Unlike the Anopheles mosquito, which transmits malaria, it is not active at night.)

While dengue fever is not as serious a threat as malaria, which afflicts up to 500 million people and kills 1 million each year, both diseases have flourished since DDT, the pesticide that controlled mosquitoes more effectively and inexpensively than any other, fell out of favor in the 1960s. Uncontrolled urbanization and its accompanying population growth, along with inadequate water management systems, have also played a role in the spread of dengue fever.

Dengue fever is caused by any of four variants of a flavivirus, DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3 and DEN-4. Other flaviviruses cause West Nile, yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. While infection by one of the dengue variants confers lifetime immunity to it, a person can still be infected by any of the other three.

The evidence strongly indicates that it is the second infection (though not the third and fourth) that can lead to a far more serious form, dengue hemorrhagic fever, in which the capillaries leak fluid. If not treated soon enough, the hemorrhagic form can result in a life-threatening loss of blood volume and death from dengue shock syndrome.

There is no vaccine for dengue fever and unlikely to be one anytime soon. In 2003, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation pledged US$55 million over six years to foster the development of a vaccine for dengue fever and stop its global spread. Vaccine trials are under way in several tropical areas, but approval of an effective vaccine is not expected for perhaps a decade.

The bite of an infected mosquito is followed by an incubation period of three to 14 days, most commonly four to seven days, before symptoms might appear.

Many people experience only mild flu-like symptoms, or none at all. In others, the characteristic symptoms of dengue fever are the sudden onset of high fever, a severe headache in the front of the head and excruciating pains in the joints and muscles — leading to its colloquial name of break-bone fever.

The fever typically resolves in three to five days, but in 1 percent of patients the disease progresses to the hemorrhagic form. Even if a first infection causes no or few symptoms, a second infection can increase the risk of the hemorrhagic form.

Since none of the known antiviral drugs are effective, treatment is symptomatic. Acetaminophen is given to reduce fever and pain. But all aspirin-like drugs, including ibuprofen, must be avoided because they can cause bleeding and make matters worse. As with other viral diseases, children with dengue fever who are given aspirin can develop Reye syndrome.

Patients should rest and drink lots of fluids. In most cases, symptoms resolve in a week or two. The disease is likely to have progressed to its more dangerous form if fever is followed by a low body temperature, severe abdominal pain, prolonged vomiting and mental changes like confusion, irritability and lethargy. Immediate hospitalization and intravenous fluids are then essential. Full recovery to a normal energy level can take months.

Based on studies of military and relief workers, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the risk to those who visit a dengue-endemic area as one illness per 1,000 travelers. This is likely to be an overestimate for ordinary travelers, most of whom stay only a few days in air-conditioned hotels with well-kept grounds.

Though many trips to Brazil this year were canceled during the epidemic in Rio, travelers do not need to avoid dengue-endemic areas if they are willing to take precautions to avoid mosquito bites.

The CDC recommends staying in well-screened or air-conditioned areas whenever possible (not a realistic option for sightseers and adventure travelers like me); wearing clothing that covers the entire body, including long sleeves and pants with tight cuffs; and covering exposed skin with insect repellent containing DEET at a concentration of 20 percent or 30 percent, applied three times a day. Though neither I nor my tripmates could tolerate full-body attire during Cambodia’s humid, 30° C-plus days, we all doused ourselves daily with repellent.

In very sunny places, sunscreen should be applied first, followed by the repellent. It also helps to spray clothing with a repellent.

Since the mosquito breeds in small amounts of fresh water, eliminating standing water in places like flowerpots and old tires can reduce exposure to this dengue carrier.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the