On the surface, Stars (星光傳奇), a movie that tracks the fortunes of One Million Star (超級星光大道) pop idol competition contestants, seems nothing short of a commercially calculated attempt to exploit the popularity of a show that took Taiwan’s entertainment industry by surprise last year.

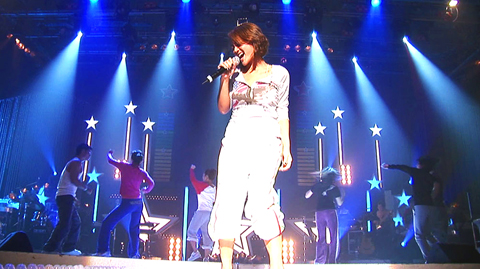

In all fairness, the well-executed documentary, which follows the second season’s hopefuls’ pursuit of fame and fortune, is smooth and pleasant to watch and technically proficient. Glances of the players’ offstage lives save the film from descending into a hollow publicity vehicle — just — and reinforce the plebeian fantasy that any Tom, Dick or Harry could be plucked from obscurity and catapulted to fame and fortune.

Second-season champion Yuming Lai (賴銘偉) is portrayed as swinging between the traditional and the contemporary as a rocker, medium and member of a divine dancing Eight Generals (八家將) troupe.

Rachel Liang (梁文音) steals the show as an orphaned Aborigine, as does Gina Li (李千娜), for being a young single mother of two.

By underscoring the importance of dreams, hope, family values and friendship to the show’s appeal, the movie readily positions itself as an auxiliary product of a successful showbiz commodity.

The documentary’s producer, Chan Jen-hsiung (詹仁雄), said the contests’ power to move audiences lies in the honesty and innocence that the young aspiring singers exhibit.

Veteran producer Wang Wei-chung (王偉忠) concludes that the show’s success comes from the contenders’ unreserved displays of emotion.

Unfortunately, the documentary fails to take a more cerebral look at the mechanisms behind the TV program’s popularity and, therefore, leaves the One Million Star phenomenon largely unexplored.

By the final scenes, the seemingly endless group hugs and tears are enough to wear down even the most cynical of viewers. The formula is a winner, even if the film is not.

Also See: One Million Star Film Notes

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the