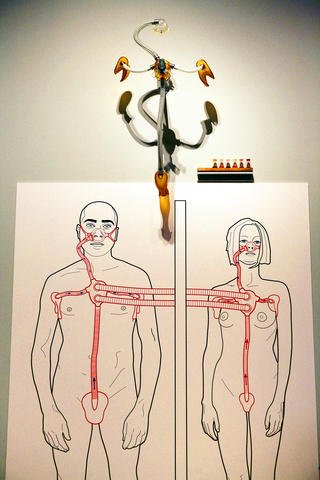

In the drawing, a nude man and woman stand on either side of a wall. Each wears a plastic breathing mask that covers the nose and mouth; the masks are connected to air hoses that pass through the wall. The hoses attach to pouches at each other's underarms and crotches.

It's a device that allows people to sniff each other. Remotely.

Things can get weird when the worlds of science and design collide. A new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Design and the Elastic Mind, contains more than 200 arresting and provocative objects and images that may evoke a "whoa" or an "ugh" or simply "huh?"

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

When art museums take on science, the results are often pretty but superficial, with blown-up images from under a microscope or through a telescope and artificial colors, said Peter Galison, a Harvard professor of the history of science and of physics. He said this "out-of-context aestheticization" was not just "kitschy," but could also kill the depth and context that made science interesting.

Design and the Elastic Mind, Galison said approvingly, is different - playful, yet respectful of the science that informs each object on display. "It's science in a new key," he said.

In this exhibition, Paola Antonelli, senior curator in the museum's department of architecture and design, gathered the work of designers and scientists, meeting in the sweet spot on a cultural Venn diagram where the two disciplines overlap.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The exhibition came together through an unusual process, Antonelli said. Some two years ago, she began talking with Adam Bly, the editor of a hip science magazine, Seed, and asked him to collaborate with her on a series of salons devoted to exploring the relationship between science and design.

"At the beginning it was this sort of apology-fest," Antonelli said. She recalled the way scientists would open their talks by saying, "I don't know what art is," and the artists would say they did not know any formulas. Through the salons - with speakers like Benoit Mandelbrot, a mathematician who pioneered the creation of gorgeous images from mathematical functions, and leading designers - the outlines of an exhibition took form.

The works that come from laboratories have a quality that can evoke wonder: a soft-bodied robot designed to move like a caterpillar, and movies of a circular pool with wave-generation machines ringed around it that beat the water in rhythms and that can form letters of the alphabet. And, yes, some images come from under microscopes. But they stay true to their scientific roots, said Paul Rothemund, a scientist at Caltech, whose work is on display. He manipulated molecules of DNA to create a series of microscopic smiley faces that are one one-thousandth the width of a human hair.

"The work isn't mere artwork," he wrote in an e-mail message in response to questions. "Artwork is necessary for engineering and science."

The designers tend to approach the work with a bit more puckishness. There are visual displays of data that present, for example, thousands of personal advertisements in a heart-shaped flux of bubbles that can be searched and manipulated. And there are the smell tubes. The designer of the Smell (PLUS) project, James Auger, said he wanted to underscore the diminished importance the sense of smell had in our lives by creating a device that allowed people to smell each other's bodily scents before they met. It would be a kind of olfactory blind-dating service.

Is it a serious proposal? Auger, who is from Britain, hedges. The science of smell, he notes, is serious, and he cites research into smell as a marker for genetic compatibility. He said he was fascinated by science and scientists, who were "creating amazing possibilities of what it means to be human. But they don't necessarily understand what to be human is. That's where design can play a very important role."

So while scientists have studied the ways that smell might have developed to warn humans of food gone bad or an approaching fire, it is up to designers to encourage people to think about what is lost when we have "fire alarms and sell-by dates and fridges" and, for that matter, deodorants and perfume.

Other projects try to build by nature's plan. Joris Laarman, a designer in the Netherlands, is designing chairs and sofas based on his research into the way that bone grows - giving support where needed and removing material where less support is required. A result is an eerily elegant assortment of legs that form a whole, using software that mimics evolutionary processes. "I try to create beautiful objects that make sense," Laarman said.

And what can we make of the display of "dressing the meat of tomorrow"? It is a fanciful representation of what meat might look like when tissues for food can be cultivated cheaply in vats instead of through grazing and slaughtering. Practical applications that would bring the cost of "cruelty-free" tissue down to affordable prices are years away, at best.

But James King, a British designer who created the prototype for the brave new meat, said edible tissues from the lab opened possibilities for what cultured meat might look like. "It's not designed by the anatomy of the animal," King said. Instead of slabs of steak, he envisions a delicate design that resembles "the cross section of a cow."

Some of the objects have an otherworldly beauty. Tomas Gabzdil Libertiny, who lives in the Netherlands, studied bees and developed scaffolding he could use to enlist them in the manufacture of objects. His beeswax vase, a golden wonder that droops slightly on a pedestal near the entrance to the exhibition, exemplifies what he calls "slow prototyping." Like the "slow food" movement, he sees his vase as showing the way to a kind of thing that demands attention and respect, in part because it is not just knocked out by a machine - it embodies, he said, "the sort of thrill in the heart that you get when you see an object that has magic."

Mandelbrot, a professor emeritus of mathematical science at Yale, spoke with joy in an interview about the new exhibition, but also with an air that suggested he was wondering why it had taken so long for the world to catch up to him. "I have been fighting on that front for a very long time," he said.

Mandelbrot said the separation of science and aesthetics had always puzzled and frustrated him, though now "the separation is decreasing, or vanishing," as more people find ways to bridge the gap.

Bly, of Seed, agreed. Bringing diverse disciplines together corrects a mistake in intellectual history and "harks back to the Renaissance," he said, adding: "We created disciplines. Nature didn't create disciplines.

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu

There is a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) plot to put millions at the mercy of the CCP using just released AI technology. This isn’t being overly dramatic. The speed at which AI is improving is exponential as AI improves itself, and we are unprepared for this because we have never experienced anything like this before. For example, a few months ago music videos made on home computers began appearing with AI-generated people and scenes in them that were pretty impressive, but the people would sprout extra arms and fingers, food would inexplicably fly off plates into mouths and text on

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions