Next time your neighbor blasts his leaf blower when you're trying to sleep in, don't get mad, don't get even.

Just shamu him.

It'll hurt you more than it hurts him, but in the end you'll reclaim your sanity.

Then you can aim your shamu voodoo at your whiny kids, forgetful spouse and demanding boss. When peace descends, congratulate yourself on a job well done.

Or, as journalist Amy Sutherland would say, "Give yourself a mackerel."

Sutherland's calmly rational approach to irritating behavior grew out of her research for a book about exotic-animal training - especially the positive reinforcement techniques that sprang from the world of marine mammals.

Hence her term, to "shamu."

The technique is simple, at least on paper: Ignore unwanted behavior, reward desirable behavior.

After trying it on her own homo sapiens domesticus - her husband, Scott - Sutherland wrote a column for the New York Times about how animal-training methods had improved her marriage. It became the Times' most e-mailed story of 2006.

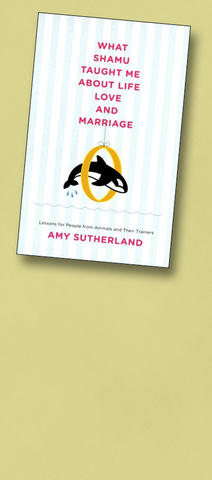

That was all the positive reinforcement Sutherland needed to pony the column into a book, What Shamu Taught Me About Life, Love and Marriage.

"Most people are pretty intrigued by the idea," said Sutherland, who reports that her immersion in the world of animal training had a surprisingly "transformative" effect on her life.

"The biggest difference in me, personally," she said, "is I do have a lot more self-control and a lot more patience and I take things a lot less personally."

It would be easy to feel miffed at Sutherland's premise that people can be trained like (other) animals. In fact, after her column ran, she heard from some irate men who complained that her premise was dehumanizing and manipulative.

To which we say, "Down, Simba." Once you read her book, which combines a breezy, bemused tone with a sense of her deep appreciation for animals and their caregivers, it's pretty hard to take offense.

"The thing is, we are all trying to change other people's behavior all the time," Sutherland said, "and most of us do it by what animal trainers would consider negative interaction - nagging, criticizing, yelling and heaping lots of attention on behavior they don't like."

It's not easy. Shamuing - applying the positive methods of progressive animal training to the annoying stuff humans do - is way harder than nagging because it requires that you replace knee-jerk reaction with restraint and thought.

"You have to change yourself," Sutherland said. "That's the thing - people want the other person to do all the heavy lifting."

The behavioral odyssey began four years ago when Sutherland, an adjunct professor of journalism at Boston College, shuttled to California to follow students at Moorpark College's Exotic Animal Training and Management Program, which she calls the Harvard of animal training. The result was Kicked, Bitten and Scratched, her book about the world of animal trainers.

Moorpark students learned to become hyperaware of the unintentional messages their own behavior could trigger in animals as diverse as raptors, snakes and baboons. Should Kiara the lioness roar in their faces, students were admonished not to flinch, for Kiara might regard any reaction as rewarding.

Deeply impressed by the trainers' "epic amounts of self-control," Sutherland started applying their methods at home. Scott quickly became her favorite guinea pig.

"We were happy," she said, "but, like a lot of couples, we had a lot of little snags in our relationship."

Scott tended to run red lights (he called them "long yellows"), eat the last cookies ("I thought you were done"), race around searching for his wallet and keys and leave stinky bike clothes on the bathroom floor.

Adopting the mindset of a trainer, Sutherland decided to stop taking his behavior personally, as if it were a swipe at their relationship.

Since it's important for trainers to know their species, she looked at him dispassionately and saw that many of his annoying habits grew from fundamental traits. His dreaminess is what made him a good writer. His diminished sense of smell well, that contributed to his heedless attitude toward his bike clothes. She'd have to work on that.

Hold the sarcasm. Opportunity knocked the day Sutherland noticed that the sweaty reek was gone from the bathroom - and so were Scott's bike clothes. Jeez, did he actually put them in the washing machine?

As he bounded past her down the stairs, she reinforced his good behavior - "Thank you," she called - and ignored the musty, wet spot on the carpet where he'd dumped his clothes in the first place. No sarcasm, no cracks.

Soon Sutherland turned her positive techniques on her mother, her neighbors, her dogs and even imperfect strangers.

When a postal clerk snapped at her for labeling a package incorrectly, Sutherland didn't snap back, apologize or flash an ingratiating smile - all of which would have reinforced the clerk's undesirable behavior.

Instead, she blankly, quietly, fixed the label. Her lack of response, known as a "least reinforcing scenario," was designed to signal wrong behavior without reinforcing it. In fact, Sutherland said, her lack of response seemed to throw the clerk, who ended by wishing Sutherland a good day. Only then did Sutherland look her in the eye and say, "You, too."

"It's the fundamental idea that any kind of response could fuel a behavior," Sutherland said.

Yelling is a case in point. Though it's designed to punish bad behavior, it may do just the opposite.

"In the human world," Sutherland said, "some people don't mind being yelled at. I know people who seem to relish it."

Though Sutherland doesn't recommend you flaunt your clever training methods, it turns out Scott is a highly perceptive animal.

"Are you shamuing me?" he'd ask when Sutherland failed to react to one of his surefire annoying behaviors.

It became a family joke, and "in pretty short order," Sutherland said, "he was doing it with me."

Now when she whines he ignores her, instead of trying to offer solutions that just irritate her because they interfere with what she really wants to do - whine.

In the end, you have to wonder who's being trained here. To Sutherland it's no contest.

"I'm the one who changed," she said. "I changed my behavior. He's still an individual with free will, and how he responds is up to him."

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields

The launch of DeepSeek-R1 AI by Hangzhou-based High-Flyer and subsequent impact reveals a lot about the state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) today, both good and bad. It touches on the state of Chinese technology, innovation, intellectual property theft, sanctions busting smuggling, propaganda, geopolitics and as with everything in China, the power politics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). PLEASING XI JINPING DeepSeek’s creation is almost certainly no accident. In 2015 CCP Secretary General Xi Jinping (習近平) launched his Made in China 2025 program intended to move China away from low-end manufacturing into an innovative technological powerhouse, with Artificial Intelligence