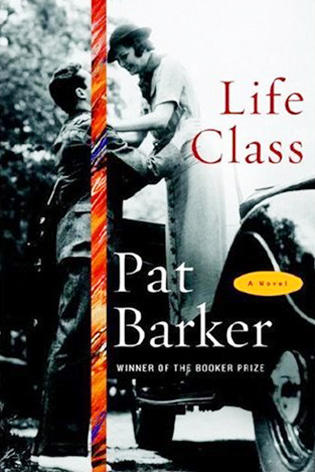

With her new novel, Life Class, Pat Barker returns to the subject of World War I - a subject that earned her immense acclaim in the 1990s with her Regeneration trilogy (Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road), an artful improvisation on the lives of the poets Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves and their compatriots, which unfurled into a fierce meditation on the horrors of war and its psychological aftermath.

After several intriguing but lumpy novels set in the present or near-present, it becomes clear to the reader that World War I resonates with Barker with special force, for Life Class possesses the organic power and narrative sweep that her recent books with more contemporary settings lack.

Perhaps it's that Barker's tactile ability to conjure the fetid horror of the trenches and the field hospitals has little applicable use in describing daily life in modern-day Britain. Perhaps it's that her narrative abilities are spurred by the sort of galvanic changes ushered in by the Great War - a social and cultural earthquake that helped midwife an era of modernism and irony and doubt. Perhaps it's that historical research (more than a dozen works are listed as source material at the end of this volume) and the use of historical characters somehow lend ballast and gravitational weight to her imaginings.

In any case, Life Class represents her best work since The Ghost Road, for which she received the 1995 Booker Prize.

The three central characters in Life Class are students at the Slade School of Art in London, studying under the tutelage of the famous Henry Tonks. Elinor, the charismatic center of the love triangle, seems loosely based on Dora Carrington, the talented painter who would become a Bloomsbury acolyte. Her suitor Neville seems loosely based on Christopher Nevinson, an art student who served with the medical corps and who later became known for his paintings of the war. Elinor's other suitor, Paul, in contrast, seems more like a full-blown fictional creation - a sort of Everyman, like Billy Prior in the Regeneration novels, representative of the many Englishmen of his generation who found their lives and expectations turned upside down by the Great War.

When we first meet these three young artists, war is still just a distant rumor on the Continent, and they and their fellow students are pursuing a bohemian life in London. There are lots of late nights out, lots of flirting and romantic intrigue, lots of ruminating about art and aesthetics and the meaning of Beauty and Truth. Paul has a brief affair with a model named Teresa and an unpleasant encounter with her estranged husband, who has been stalking her.

After Teresa leaves town, Paul finds himself increasingly drawn to her friend Elinor, one of the Slade's more gifted students, who is being pursued by Neville, a former Slade student who has started to establish a reputation as an up-and-coming painter in London. The three hang out together as friends, but Paul and Neville vie for Elinor's attentions. Neville worries that Paul might have more in common with Elinor than he does.

Paul worries that Elinor won't sleep with him and that he might not have enough talent to make it as an artist. And Elinor worries that all the independence she's established in London as a woman and an artist count for nothing with her relatives, who regard painting as little but a pleasant hobby.

All this changes with the arrival of the war, which suddenly makes all their reveries about love and art seem childish and naive. Paul ends up in Belgium working as a medic, tending to the wounded, and Neville ends up in a nearby town, driving ambulances.

Elinor, alone, remains committed to "an iron frivolity," determined to pursue her painting and ignore all news of the war. She visits Paul in the small Belgian town near the front where he is serving - one of the novel's few sequences that feels improbable and forced - and the two promptly start squabbling about the proper role of art in wartime. Paul argues for an art that would bear witness to the wounds of war - "it's not right their suffering should just be swept out of sight," he says of the wounded soldiers - while Elinor declares that art should only depict "the things we choose to love," not things "imposed on us from the outside."

In depicting the effect that World War I has on her three young protagonists, Barker takes care never to sentimentalize them. Although she writes effectively from each of their points of view, communicating their hopes and fears and dreams, they emerge as rather selfish, unsympathetic individuals, who have all cultivated a certain emotional detachment in the service of their art. That detachment helps Paul and Neville survive the horrors they witness during the war, but it also cuts them off from genuine emotional connection.

Elinor's determination not to think about the war comes off as narcissistic denial. Neville's celebrated success in London with his war paintings feels perilously close to war profiteering. And Paul's "learning not to care" about the wounded soldiers he tends to sometimes seems less like a defensive survival mechanism than a solitary man's rationalization of his own difficulty in feeling.

As she did in her Regeneration trilogy, Barker conjures up the hellish terrors of the war and its fallout with meticulous precision. Grievously injured soldiers crying out for morphine that does not exist; field surgeons tossing bits of damaged flesh into buckets; civilians scurrying for safety as bombs torpedo their homes and gardens; columns of rain-drenched men marching toward the front in "gleaming capes and helmets, like mechanical mushrooms" - such images and the ineradicable memory of these sights are captured with unsparing clarity by Barker in these pages, as are the less visible scars they leave on the psyches of soldiers, doctors and witnesses alike.

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields

The launch of DeepSeek-R1 AI by Hangzhou-based High-Flyer and subsequent impact reveals a lot about the state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) today, both good and bad. It touches on the state of Chinese technology, innovation, intellectual property theft, sanctions busting smuggling, propaganda, geopolitics and as with everything in China, the power politics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). PLEASING XI JINPING DeepSeek’s creation is almost certainly no accident. In 2015 CCP Secretary General Xi Jinping (習近平) launched his Made in China 2025 program intended to move China away from low-end manufacturing into an innovative technological powerhouse, with Artificial Intelligence