Much of Asia can still be rightly described as displaying a "massage culture." Sex, nominally disguised as massage, is offered by the attractive but impecunious young to the better-off males in establishments that have, to local eyes, nothing disreputable about them. European men discovered this age-old phenomenon with a sense of disbelief - its equivalents had long been banished, certainly in Anglo-Saxon countries, under the various manifestations of Puritanism. Thailand went on to built a tourism industry on its immemorial leisure-time habits, while in Japan the ancient structures were modified only by the arrival of general affluence. This has led to nostalgia there for the old ways, and in particular a fascination with the lifestyle and traditions of the geishas.

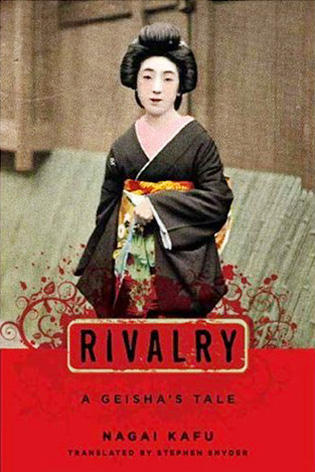

Rivalry: A Geisha's Tale, fresh from Columbia University Press in an English version by Stephen Snyder, is the first ever translation of the full text of the masterpiece of the early 20th century novelist and short-story writer Nagai Kafu. An earlier translation was only of a commercial edition that didn't include long erotic passages added later by the author for a private printing - he knew in advance that they'd be unacceptable to the government censor.

Nagai Kafu is a fascinating figure. Originally an editor of literary magazines specializing in the newly-fashionable French naturalism, he abandoned that work in order to embark on a life investigating Tokyo's erotic underworld. This was partly done, no doubt, for its own sake, but it was also undertaken in a spirit of devotion to the ethos of the old, pre-modern Japan, the traditions of which Kafu felt were in part preserved in the teahouses and theaters around which the geishas and other women of the night circulated.

Rivalry is a wonderful novel, with clearly distinguished characters, a swift narrative style, rich descriptions and incisive analyses of feelings and motives. It's set around 1912, and evokes a capital city already equipped with telephones, newspapers, cigarettes and trams. There are stockbrokers, new sessions of parliament and year-end sales. But still defining the life in the pleasure quarters are the ways of the Edo period which had ended over 40 years before, so that geishas continue to preside over the tea ceremony, dress with astonishing formality, and entertain rich businessmen, initially at least with performances on the shamisen.

Kafu understands perfectly well that differences of money, and hence of power, lie behind the sexual games his characters play. The geishas are contracted to the houses they work out of, and one of their main ambitions is to find a patron who will pay off this debt and set them up in financial independence. But at the same time they are young and sensual beings, falling in love with kabuki actors of their own age even while conducting by no means platonic affairs with their older clients. This is part of the rivalry of the title, and it's the main character's love for a young actor that triggers the fury of her patron, Yoshioka, even though he's by this time become tired of their sexual relationship and is looking around for new pleasure elsewhere.

It's strange that a novel as good as this has remained unpublished in English in its complete form for so long. It's true that for many decades after the extended edition was published in Japan (in 1917) passages from it would not have been permitted in, for instance, the UK. There are by no means disapproving references to oral and anal sex, for example, and the writing in general has an open-mindedness about it that is extremely refreshing. Even so, it has been through Arthur Golden's 1997 bestseller Memoirs of a Geisha - also a novel, though cast as an autobiography - that most modern readers have gotten to know about the geisha traditions. Kafu's older classic, by contrast, will please aesthetes and lovers of genuine literature far more.

There's a long-standing tradition among Japan specialists of insisting that geishas were high-class entertainers most of whom would never allow the men they entertained to lay a finger on them. This is a long way from Kafu's view, and he was in an ideal position to know. Indeed, the description of one particularly outrageous senior geisha, Kikuchiyo, is so replete with sexual detail that I had to read it twice before I could believe my eyes.

But Kafu was no smut-peddler. At heart he was a lover of ancient Chinese poetry, like the writer Kurayama Nanso in the novel. Indeed, one of the characters he mocks most vigorously is Yamai, the editor of a new magazine specializing in pornographic photos. But then one of the attractions of this wonderful book is its range, even given its relative brevity and concision. There are as many different types of character, and of emotion, as there are in Tolstoy, even though Kafu's true masters were probably Maupassant and Turgenev, social realists with a sympathetic eye for subtleties of situation and nuances of feeling.

Kafu was an aesthete fascinated by sex, and predictably he had his own theory of desire. Whereas men of old sought to prove their masculinity in war or hunting, in the modern world they seek to do it by success in the fields of business and sexual predation. Yoshioka is his prime example of this, a handsome married man possessed of "an endless repertoire of obscene tricks," adept at concluding affairs, and endlessly seeking out new conquests "from girls of sixteen to women past forty." He finally finds his match in the frankly sensual Kikuchiyo.

Stephen Snyder is to be thanked both for translating this half-forgotten novel at all, and for doing it so compellingly. He is, incidentally, also the author of a critical book on Kafu entitled, appropriately enough, Fictions of Desire.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she