The Neva was still covered in a thick layer of ice in March. Skaters whirled out in the middle of the wide river on which St Petersburg stands. Cold, somber sunlight filtered into the gallery high above. And that was when I saw them for the first time, the red bodies whirling and yet still, linking hands, looking downward as they cycle in the blue: the dancers.

There in that wintry room in Russia's great museum, the State Hermitage, was the most beautiful painting of the modern world. There is an unreal and utopian quality to Henri Matisse's Dance. And its strange story has recently become stranger still. The painting, completed in 1910, was confiscated from its Russian owner after the 1917 revolution and vanished. It was nearly destroyed for being decadent during the Stalin era, eventually became visible to Westerners after the downfall of the Soviet Union and, in the past few weeks, has been at the center of a Cold War-style diplomatic drama.

The painting was set to be the star of an exhibition of modern masterpieces, From Russia, at the Royal Academy later this month. Then, last month, the show was abruptly cancelled. Russia took fright that paintings taken into state ownership after the revolution had no protection from legal seizure in Britain. Only fast-tracked, anti-seizure legislation has saved the show.

PHOTO: AFP

Matisse's masterpiece is the most glorious work of art the British will see in the capital this year. Savage and classical, ancient and modern, civilized and barbaric: Dance is all these things. Its beauty comes from a time and a place when art was being remade.

Matisse's five dancers are outlined in thick brown lines that notate simple anatomical details - breasts, buttocks, leg muscles - in a deliberately gauche and childish way. A foot at the far left of the picture is a tangled blur; and what's that bungled attempt to delineate the stomach of the dancer at top right? Yet no one can seriously mistake the roughness of Matisse's drawing for incompetence. The masculine-looking dancer at the left edge forms a perfect geometric curve. Matisse does everything he can to tie his ethereal imagination to basic physical facts. One dancer throws her head forward over a twisted, bulging stomach and muscular, wide-flung thighs. The rawness of her physique releases the painting's sheer visceral power. It's hard to miss the fact that she resembles some tribal carving or neolithic fertility idol. This painting reconnects jaded modern eyes with the primal origins of art.

It is nearly 4m wide and 2.5m tall in only three colors: blue, green and red. Matisse is one of the greatest liberators of color in the history of art and here he puts color at the service of a great revolt.

In the first decade of the 20th century, any adult - including Matisse, born in 1869 - would have grown up in the Victorian age. Even in Paris, where artists had long made a virtue of shocking moralists, sex was disreputable. Now, suddenly, here is Matisse's Dance, a painting that declares there is no higher, no more human thing than to dance in naked ecstasy: to burn with passion.

And yet the image Matisse uses is one of the most ancient in art. From Etruscan frescoes to Botticelli's Primavera to Turner's landscapes, the story of art is full of dancers.

To compare Matisse's Dance with, say, Botticelli's Primavera is to recognize Matisse's originality and modernity. From the Primavera, the goddess Venus looks out. That gaze has a basic way of connecting painting with the world we inhabit.

In Matisse's Dance, only one of his dancers shows her face - and it is cast down. This is a private revel, a party we can watch but that will happen with or without us. The painting deliberately risks what every previous artist had gone to great lengths to avoid when painting the good life - an inhuman remoteness.

To grasp what it was that drove Matisse to such unprecedented creative fire, you have to look to a dramatic tension between two geniuses. At the time no one seems to have noticed; only now, a century on, can we see this work as a stratagem in a competitive game with Pablo Picasso.

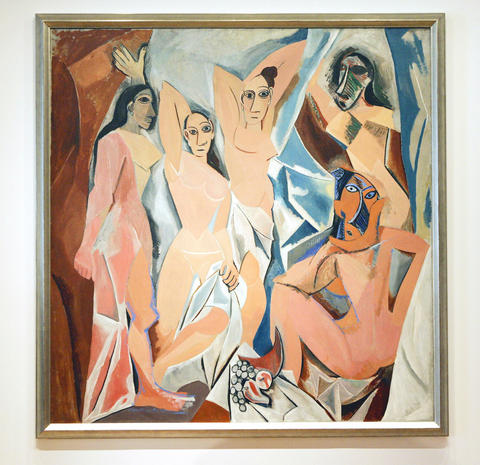

If earlier Bacchanalian paintings engage the beholder in sensual conversation, Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon stares you down. Five women stand in a compact, jagged curtained theater. Even the slice of melon looks as if it could do you an injury. Two have grotesque masks for faces, yet all are looking at you. Eyes burst from the pink and blue canvas. The young Picasso created his masterpiece, a big square picture on the ambitious scale of a history painting by Poussin, in 1907, in his studio in the ramshackle Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre. Three years later, Matisse composed his answer to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon: Dance.

Matisse, 12 years older than his Spanish rival, had come to art at 19 when he was convalescing after a breakdown that came of trying to force himself into a law career. Soon after, he was studying under the symbolist painter Gustave Moreau and by 1905 was seen as positively dangerous.

Nineteenth-century art movements always justified their departures from convention with the sincere claim that they were painting the world as it really looked. For the first time, in 1905, Matisse and others started to splash on color and made no such claim. People called them fauves, "wild beasts."

Yet even fauvism came to seem tame in comparison with a new revolution that was brewing. It came not from art but from history, trade and geography. In the late 19th century, European nations were competing to colonize the world. And with that a multitude of artifacts from tribal cultures in Africa and the Pacific started to reach museums, art dealers and markets.

It is exhausting to follow the rapid succession of events and ideas in avant-garde Paris around 1906. Matisse was painting a primal scene of six naked dancers in Le Bonheur de Vivre. That same year, the collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein introduced him to Picasso, and Derain bought an African mask he showed to both artists. It survives, a white, wooden oval with piercing eyes from Congo. The faces of Picasso's prostitutes in Les Demoiselles are blatantly modeled on it. But how does African art infect Matisse's classical, Arcadian Dance?

Les Demoiselles is so savage, so aggressive, it horrified even the avant-garde artists who saw it in Picasso's studio. It was not exhibited until years later. Only since its acquisition by MOMA in 1939 has it become an icon. Matisse, however, understood it. Dance, his response, infuses the ancient classical tradition of the Mediterranean with the "primitive" energy of masks and rough-hewn tribal sculptures. Most of the African and Oceanian masks these artists were collecting were, after all, made to be worn during ceremonial dances. The Russian businessman Sergei Shchukin fell for the art of Matisse after seeing Le Bonheur de Vivre. Their relationship became like that of Renaissance artist and patron, with Matisse accepting commissions from Shchukin. In 1908, they went to Picasso's studio to see Les Demoiselles d'Avignon - a visit of great significance for both.

Shchukin commissioned Matisse to create mural-scale decorative paintings for his Moscow mansion, and Dance is the result. Matisse's determination to outdo Picasso on the large, historic scale of Les Demoiselles could scarcely be more obvious. Both paintings present the same number of nudes, but where Picasso painted five women who challenge the viewer, Matisse answers him with a picture whose five naked inhabitants don't care if you are there or not.

Dance is modernist in a way that has not faded. When you look at it, you are unsettled as well as uplifted. If Les Demoiselles contains within it the seeds of dada and surrealism and every impulse in modern art to unleash dark forces, Matisse, in the final, 1910 version of Dance, anticipates abstract art, minimalism and every artwork that invites the dismissal: is that all?

There's nothing in any other painting quite like the chromatic miracle of Dance. Terra-cotta flesh combines mysteriously in your mind with those saturated blues and greens, in a poem of absolutes. And here Matisse's understanding of the "primitive" becomes clear. For all its Hellenic grace, Dance is as much a willfully barbaric painting as its rival by Picasso. The key to its barbarism is color. There is something simple, childish, folkloric about rampant color.

An unlikely source for the figures in Dance was an artist - a primitive in Matisse's eyes - who lived in the heart of a modern city: J.M.W. Turner. Matisse made a special study of this overwhelming British colorist on his honeymoon in London in 1898, when he looked repeatedly at Turner's art in the National Gallery. You could hang Dance next to Turner's paintings and the emotional use of color to blaze a path between the imaginations of artist and beholder would immediately strike you as similar. Turner's Mediterranean scenes are peopled, too, with Arcadian figures. The five figures in Dance look uncannily like a group of dancers in Turner's The Golden Bough and reminiscent of dancers in other Turner paintings. What makes them so similar is the serpentine loose depiction of the bodies, which in Matisse is deliberate and in Turner's model was an accident. Turner didn't paint people very well. His figures are ungainly, rough.

I think this is crucial to the meaning of Dance. The simplest, most humane discovery of modern artists at the beginning of the 20th century was that art is not a matter of drawing "correctly." Dance exemplifies the modern belief that to evoke the important things you don't need to pay attention to any protocols. Turner had faults, but his vision makes these irrelevant.

Matisse's conception, a century after he painted Dance, is still lethally elusive. Those red dancers flit and flicker away from you like glinting fish in the water when you try to grasp them. They slide off, they dance away. Such bliss, such ecstasy - and it is yours, but not yours. It is a painting that eludes the analyst. Matisse's art suggests there is something, some experience, some truth that we cannot touch with our hands, cannot capture with language, but must treasure in the moments it comes to us - if it comes to us at all.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the