Dengue fever is a Los Angeles band featuring a Cambodian-born singer and five American alt-rockers who regularly embarrass her onstage.

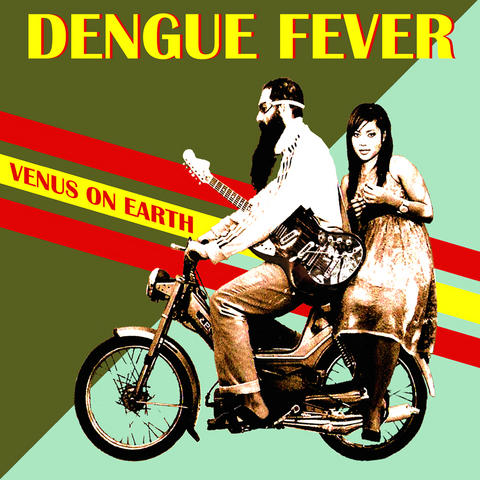

On the cover of its new album, Venus on Earth, the guitarist Zac Holtzman, with a long beard and goggles, drives a scooter with the vocalist Chhom Nimol sitting demurely behind him sidesaddle, the way a good Cambodian girl would ride through the streets of Phnom Penh. Dengue Fever, which specializes in an unlikely mix of 1960s Cambodian pop, rock and other genres, is a lot like that image. Propriety and smart aleck indie rock race by, blurring together.

It is a band of rollicking lightness that keeps coming up deep. At a recent show in the Echo Park neighborhood here, the male members were downright goofy, but Chhom, singing mostly in Khmer and dressed in shimmering Cambodian silk garments she designs herself, looked like old-school royalty, a queen before the hipoisie. No wonder she seemed to roll her eyes from time to time onstage. But after the set, when she lighted a candle onstage to honor those killed by the Khmer Rouge, her voice broke and tears ran down her face.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEVIN ESTRADA

"I think we balance each other out," Holtzman said in a recent interview. "She'll bring the whole place to a hush, and that would be a long night if it was just that. And then we smash the place up."

Dengue Fever formed after the Farfisa organ player Ethan Holtzman, Zac's brother, traveled to Cambodia in 1997, discovered 1960s Cambodian pop and returned with a stack of cassettes. This was not the sort of roots-driven folk sounds ethnomusicologists crave; this was locally produced, gleefully garish trash infused with the surf guitar and soul arrangements that Armed Forces Radio blasted across the region during the Vietnam War. It flourished until the Khmer Rouge came to power in the 1970s and functionally dismantled Cambodian culture.

Dengue Fever's music is a tribute to that lost pop. But the six members of Dengue Fever form a quintessential Los Angeles crew, with a mix of backgrounds and interests that seems fitting in a region with the largest Cambodian population in the US (in Long Beach, south of downtown Los Angeles) and a flourishing indie rock scene (in the hills east of Hollywood). The band is the musical equivalent of that ultimate modern Los Angeles marker, the polyglot strip-mall sign. It too offers a cultural mash-up; beyond the obscure Cambodian pop you can hear psychedelia, spaghetti western guitars, the lounge groove of Ethiopian soul and Bollywood soundtracks. Seeing Hands, on the new album, has an almost Funkadelic groove, while Sober Driver is an all but emo complaint about a guy who drives the cute girl everywhere and gets nowhere.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEVIN ESTRADA

Now Dengue Fever is starting to make its mark far from its hometown. The band recently returned from the Womex world music festival in Seville, Spain, where it was one of a handful of acts to play showcase performances. British publications have included it in "next big thing" roundups, and Dengue Fever's songs have been on television and film sound tracks, including Jim Jarmusch's Broken Flowers. A new documentary, Sleepwalking Through the Mekong, that follows the group on its first trip as a band to Cambodia, seems likely to gain it further notice.

"The underground people are getting hip to world music, and the world music side is getting hip to how you don't have to have a dreadlock wig and Guatemalan pants to be cool," said the bassist Senon Williams, sitting in his backyard with Chhom and Zac Holtzman.

"Now that Nimol is going to start singing more in English," he added, "it's making new things possible for us. Nimol really wants to connect with the American audience more now."

Dmitri Vietze, a publicist and marketer for many global music acts, sees the band as "part of a larger developmental pattern" in world music. "Can you stick them in the world-music bin at brick and mortar retail stores?" Vietze asked. "I don't know. But ... they are a part of a huge and promising future."

Older generations of Cambodians in California are sometimes critical. "They don't want me to show off too much of my dress," she said. "They always tell me, 'Don't forget you're a Cambodian girl.'" But the younger generation responds to Dengue Fever and even breakdances to its reinvention of a mongrel music that is itself a reinvention of a mongrel music from the West.

Folk music it's not, but in one crucial way Dengue Fever has folk resonances. To Chhom and other young Cambodians in the States, pop singers like Sinn Sisamouth and Ros Sereysothea, who died in a labor camp in Cambodia in the 1970s, hit a nerve that blues singers or hillbilly bands do for many Americans: the music takes listeners back home, to a home that doesn't precisely exist anymore.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu