About a dozen years ago, the Rough Guides and Lonely Planet series of travel books, rival bibles for the footloose and fancy free, crossed a new frontier onto the Internet. But they found their road maps to the digital future hard to read.

Guidebooks were soon overtaken online by Internet-era upstarts like TripAdvisor.com, which draws content from volunteer contributors and revenue from links to online reservations systems and advertising.

Now travel publishers are trying to catch up. They are moving more of their work onto the Internet and extending their content and brands into new areas like mobile services, in-flight entertainment systems and satellite navigation devices. Travel books are getting a makeover, too.

NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

And the recent acquisition by BBC Worldwide, the commercial arm of the British Broadcasting Corp, of a majority stake in Lonely Planet has prompted that publisher and its rivals to accelerate their search for new sources of revenue in the online world and elsewhere.

"We want to be in a position where, if the business suddenly collapses in five years, we have a plan - unlike the music industry," said Martin Dunford, publishing director of Rough Guides, which is part of the Penguin division of the media company Pearson, based in London.

So far, the digital media revolution has been much less turbulent for guidebook publishers than for record companies, which are fighting rampant online copying. Sales of travel guides, while flat in some traditionally stalwart markets like Britain, have been growing strongly in developing countries and in the US - despite a weak US dollar, which has made overseas trips more expensive for Americans.

Travel publishers sold 14.8 million books in the US last year, up 11 percent from two years ago, according to Nielsen BookScan. Still, guidebook companies may have missed an opportunity on the Internet.

TripAdvisor spotted the potential in tapping users' reviews of hotels, package trips and tourist attractions, and collecting a fee each time they click through to reserve a room, for instance, on a partner site. The site supplements users' reviews with links to sites run by guidebook publishers like Frommer's. TripAdvisor, which is owned by Expedia, does not break out financial figures separately from its parent.

TripAdvisor has clearly been a big success in reaching an Internet audience. About 3.6 percent of users of travel Web sites visit TripAdvisor in an average month, according to Nielsen Online, placing it third behind Expedia and another booking service, Orbitz. Among guidebook sites, Lonely Planet ranks first, Nielsen says.

While many travel publishers have had Web sites for a long time, some of them, along with booksellers, initially worried about cannibalizing sales of guidebooks. The easy availability of travel information online may indeed have cut into sales of guides to mainstream destinations, publishers say; Londoners traveling to Paris for the weekend are less likely than they used to be to buy an entire Lonely Planet guide to France.

But new book formats are aiming at niche interests and travelers taking short breaks on low-cost flights. Meanwhile, more guidebook content is being uploaded to the Internet, where it is often available free.

Everything that appears, for example, in the Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness Top 10 guides, which feature only the highlights of a destination, is already available online at traveldk.com, said Douglas Amrine, publisher of Dorling Kindersley travel books, another division of Penguin.

Alastair Sawday Publishing, a smaller travel publisher based in England, put all of its content, which consists mostly of hotel reviews, onto the Internet this past summer, at sawdays.co.uk. Previously, only 30 words of each review were available. Joe Green, who runs the Web site, said that the move was aimed at developing Internet advertising as a new source of revenue, to complement sales of the books and income from hotels that pay to be listed in them.

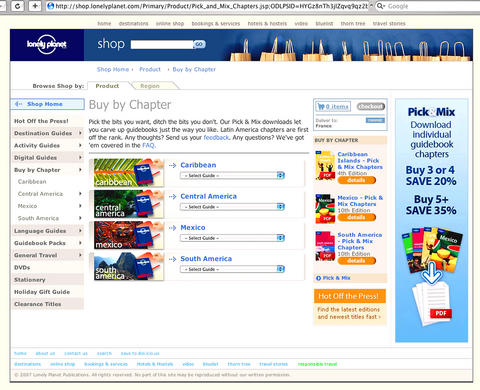

Lonely Planet plans to put all its content onto the Internet within two years, said Judy Slatyer, chief executive of the company. Not all of that content will be free, though. Over the summer, Lonely Planet began selling on its Web site, lonelyplanet.com, individual chapters from guidebooks to Latin America, pricing chapters at a few US dollars each. That way, the impulse traveler to Buenos Aires, for example, no longer needs to buy an entire book.

Slatyer said that the program would be expanded to the US this month and that other destinations would be added throughout the year. While many content owners have had difficulty getting consumers to pay for anything on the Internet, Slatyer said that sales of the chapters had exceeded expectations.

Dorling Kindersley is also trying to generate revenue directly from consumers who visit its Web site. It allows travelers to create customized guides. A group heading to Prague for a bachelor party, for instance, could assemble a list of the best bars in that city but skip information on, say, the opera.

Taking its cue from social networking services like MySpace and Facebook, Dorling Kindersley lets users share the books with other people. They can also order printed, bound copies of the customized guides for US$15.

Publishers are also making their content available in a variety of other ways. Rough Guides, for instance, has made some material available in airplane seatback entertainment systems, including those in the new Airbus A380s operated by Singapore Airlines.

Alastair Sawday Publishing recently started selling a guide to the pubs and inns of England and Wales that alerts drivers, via their satellite navigation systems, when they approach a selected watering hole or guesthouse.

Digital business still generates relatively little revenue for guidebook publishers - less than 5 percent of sales at Penguin's travel division, for example, according to executives there.

"There's been a lot of experimentation, but maybe not enough revenue coming back from digital," said Joel Rickett, deputy editor of The Bookseller, a trade publication based in London.

And publishers like Lonely Planet, which says it sells about 6.5 million books a year, are not giving up on the guidebook.

"The travel guide business, the good old-fashioned paper book, is still a strong and healthy business," Slatyer said. "And we think it will be for some time."

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,