Somewhere out there, right now, everyone's dream vacation awaits. It is a collective dream, created by travel journalists who describe, in a cascade of cliches and superlatives, a world of white-sand beaches, quaint villages and smiling locals eager to share their secret knowledge. It is a world in which all places, regardless of location, history or culture, embody a "bewitching blend of the ancient and modern."

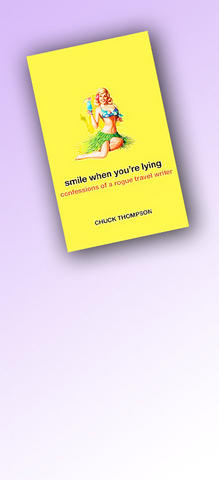

Chuck Thompson demolishes the dream in Smile When You're Lying, his acidic take on travel journalism and the multitudinous horrors that lie just beyond the airline check-in counter. As a longtime freelance travel journalist and the founding editor of Travelocity's short-lived magazine of the same name, he knows the score and he tallies it accurately.

"Actual travelers exist in real time and have to deal with the kinds of troubles that don't end up as body copy between splashy photos of a beach at dawn and coconut-encrusted prawns in honey-melon-okra dipping sauce at cocktail hour," Thompson writes. "Actual travelers have to deal with actual travel."

Actual travel might involve being seated next to a woman who, on a long international flight, scrapes and sands her callused feet, flicking bits of dead skin on your leg. Or being rolled by four Thai women and left without a penny on a remote island. Or, to draw on one of Thompson's most colorful foreign adventures, it might involve standing on a deserted stretch of highway in the Philippines at 3am, desperately waiting for an arriving bus, as eight machete-wielding men emerge from the brush and approach for a friendly chat.

These and other outtakes from his reporter's notebook add spice to Thompson's dead-on demolition job. The book is a savagely funny act of revenge for years spent servicing the travel fantasies of gullible readers, the kind who truly believe that acting like a local in London means, as one tourist guide urges, eating at one of the city's "few surviving pie 'n' mash shops." As Thompson inconveniently points out, if only a few such shops remain, "it stands to reason that not many of London's 12 million locals are eating much pie 'n' mash."

Thompson lashes out wildly. Over the years, logging many thousands of travel kilometers, he has compiled an impressive hate list. His least favorite destinations include New Zealand ("a junior-varsity version of the Pacific Northwest"), Colorado (Kansas with big hills), Austin ("if it wasn't surrounded by Texas it'd be called Sacramento"), the entire Caribbean ("a miasmic hellscape") and Eric Clapton.

Eric Clapton is not a destination, but Thompson, a former rock 'n' roll drummer and Nick Hornby-scale obsessive, does not care. In one of many insanely digressive passages, he foams at the mouth about Clapton's supposedly inflated reputation. Having settled the question to his satisfaction, he returns to it again when describing an ill-fated tour he once made in East Germany with a band called the Surf Trio. Then he has the cheek to complain about travel writers who think they're the story.

The music trivia aside, Thompson makes self-indulgence work for him. He throws in everything: his boyhood years in Juneau, his experience as an English teacher in rural Japan, his journalistic forays into weird corners of the earth for magazines like Escape, and his adventures gathering material for two guidebooks on World War II sites in Europe and the Pacific.

His personal encounters with the dark side of travel carry the book, which is more memoir than expose. He has suffered greatly, but pain only makes him laugh, even when it's a dense carpet of ants crawling up his legs in a squalid Brazilian hotel room.

Along the way Thompson has accumulated, if not wisdom, some useful tips. It is worth remembering that in the US "spicy" means "not spicy." In Thailand the word means "it's going to taste like someone shoving a blowtorch down your throat for the next 25 minutes." No white man, he cautions "should ever wear a sarong, not even in private."

In a chapter on the workings of the travel industry Thompson strongly recommends lying whenever possible to gain extra discounts on cars, hotel rooms and air tickets. No one knows that you are not the regional sales director for Microsoft. If your batteries die mid-flight, rubbing them briskly on your leg to generate static electricity can prolong their life for as much as an hour or two.

"This also works in cheap hotels where they never change the batteries in the remote," he writes.

A cloud of guilt envelops Thompson as he writes, conscious that he and his travel-porn cohorts have strip mined the earth of its most precious resource: pleasant, undiscovered destinations.

"We venerate what we destroy," he writes. "But first we destroy." By the time he got around to returning to Eastern Europe, travel journalism had done its work, specifically television travelers like Rick Steves and the Lonely Planet guides, two of Thompson's favorite targets.

"Every description sounded as if it had been lifted from a feminine-hygiene-spray commercial," he writes of one of Steves' Eastern European video tours. "Seas glistened. Cities sparkled. Hungary was a 'goulash' of influences. And, of course, the Croatian city of Split was the usual fascinating blend of ancient and modern."

How about South America instead? "Second only to the Himalayas for mountain drama, the turbulent beauty of the Andes" — but wait, could this description possibly be written by none other than Thompson? As he duly notes, travel journalists are a little like alcoholics, doomed to repeat the same story in the same words. Backsliding, apparently, is always a danger.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.