At a press-conference in Taipei last week, Ang Lee (李安) appeared the most self-effacing and generous-natured of celebrities, but also one of the most intelligent. He guessed he was "not a macho kind of guy," he said, but was instead interested in outsiders, those who suffered from the conflicts of others, and especially women. He was also devoted to diversity, he said, to making each new movie as unlike the one that went before it as possible.

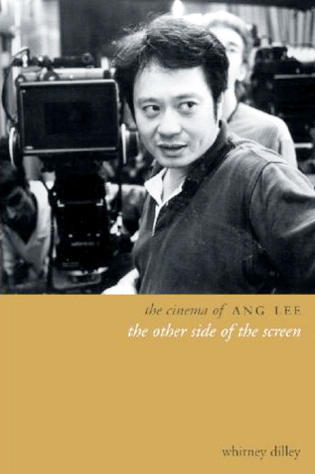

These themes and more are explored in a superb new book, The Cinema of Ang Lee. The author, Whitney Crothers Dilley, teaches English at Taipei's Shih Hsin University, and her account appears in the Directors' Cuts series from London's Wallflower Press. Taiwan is very fortunate to have someone of this quality teaching here.

This new book's essential characteristics are clarity, perceptiveness, sympathy and thoroughness. This is no coterie text for cineasts or crabbed work for academics. Instead, it's eminently clear-headed and lucid, covering all his films in detail, but also containing a perceptive and even profound overview of the inner nature of Lee's achievement.

In the author's view, Lee is on the edge of becoming - indeed, may already have become - one of the great film directors. But, as with Bergman or Fellini (directors she only refers to in passing as influences cited by Lee himself), his achievements have been on his own terms. He doesn't make movies on the orders of media moguls, but instead follows his own insights, so that each new creation is, in a sense, unexpected. Such people are best seen as major world artists who, as if by chance, have wandered into the world of film.

The diversity of Lee's oeuvre has been much remarked on. He has darted from East to West and back again, and then from one Western genre to another (after Lust, Caution (色,戒), his Asian movies are also coming to appear enormously varied). He not only makes films following his inner compulsions - he also makes them out of a sheer delight in the challenges and technical difficulties they pose. (Shakespeare's plays were also astonishingly varied in subject matter and unpredictable in style).

Lee's films are full of risk, the author claims, courting failure (and once, in the case of Hulk, discovering it). They are also free of stereotypes, filled instead with a desire to make appear normal the kinds of people who are usually considered outsiders. This she puts down to Lee's ambiguous position as an immigrant from Taiwan living and working in the US - half celebrity, but also half outsider.

One of the book's arguments is that Lee brings specifically Chinese qualities even to his American movies. The characteristics it pinpoints are a rejection of the standard Hollywood "happy ending," and a related sadness that life in reality is not what you dream it could have been. This melancholic nostalgia, the author points out, is very characteristic of traditional lyric poetry in Chinese, but it also pervades Lee's films all the way from Pushing Hands (推手) to Lust, Caution.

She also points to the power of silence in Lee's films. The focus on the plight of the individual that this silence leads to is exactly what Lee wants to achieve. As the British poet Wilfred Owen wrote about his World War I subjects, the poetry is in the pity. And so it is with Lee.

In an interesting aside on The Wedding Banquet (喜宴), Dilley remarks that the script originally had a leading character working at developing products specifically for left-handed people. This idea was later cut, but it provides an incomparable insight into where Lee's sympathies lie. The left-handed are still, in a lingering prejudice, routinely forced to use their right hands in much of Taiwan, and indeed in much of Asia. A sympathy with, and concern for, the metaphorically left-handed in many spheres of life could be said to characterize all the films of Lee.

There is a mass of incidental detail included - how President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) visited Lee at his parental home near Tainan, how the original author of Brokeback Mountain, Annie Proulx, initially doubted if Lee was the right director for it, how The Wedding Banquet was shot in six weeks for US$750,000 but made US$32 million, proportionately surpassing even Jurassic Park, and of how Lee appears himself in that movie, speaking the single but crucial line about the over-the-top wedding-day antics, "You're witnessing the result of 5,000 years of sexual repression."

Lee has said of himself "I don't have a hobby. I don't have a life," and "I would like to live inside the film and observe the world from the other side of the screen" (providing this book with its subtitle). But there's something more to this than meets the eye. It's the attitude, usually unspoken, of many of the very greatest artists. Their creations are everything, and there's no time - certainly no imaginative time - for anything much else. Shakespeare seems to have done little and traveled nowhere, while Mozart was so involved with music that his daily life reads like a sad, then a tragic, joke.

It's a big claim to make for Taiwan's most famous son, and it's not made in this book. But the point is that Lee is of that same, rare personality type, ambitious only for his work, and endlessly inhabiting a world alongside his characters - he lives, not in glamorous Hollywood, but in an unassuming New York suburb. And it's an understanding of the deep nature of her subject that makes Dilley's groundbreaking and comprehensive book such a rewarding read, and such a very fine achievement.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry