Steve Martin crosses the lobby of New York's Algonquin Hotel in what I at first take to be a disguise of some sort. It's not entirely his fault: the toothbrush moustache he wears is a condition of his lead in the second Pink Panther movie, currently filming in Chicago. But the wide-brimmed hat, our-man-in-Havana-style suit and sunglasses the size of wing mirrors are all wardrobe decisions that, along with his mildly self-conscious air, announce his arrival as subtly as a town crier.

I'd seen Martin's public persona in action at the New Yorker literary festival the day before, where he'd appeared before a full house to discuss his new memoir, Born Standing Up. The book covers the period from his childhood to his early 30s, when, with audacious ambition, he left stand-up comedy to take a shot at movie stardom. Martin reprised some of his early routines, sang a satirical song and, to the delight of the bookish audience, successfully executed a rope trick. His demeanor throughout was extravagantly pained, "I can't believe you people are making me do a rope trick," he said. "You're killing me up here." Then he sat back down to answer questions. After an hour, someone at the back got up to leave, whereupon Martin bent double and cried, "We have to finish now. People are leaving. Oh my God, I'm boring them, this is the worst possible ... ." He wasn't joking.

Martin admits in the book to being unhappy talking about himself, and the memoir skillfully circumvents much of his personal life to focus on his early career and his relationship with his parents. It's hard to reconcile its self-possessed tone with the guy we think of as Steve Martin, rubber-faced and on the receiving end of chaos. From his first film role in 1979, as The Jerk, onwards, his characters have tended to be uptight and good-hearted, lovable idiots pushed to breaking point by children, rogue weather systems or his country's hard-line insistence that everyone be happy and fulfilled at all times. In 1991's LA Story, which he wrote and produced, he obliquely comments on his own comic style by playing a surrealist weatherman whom nobody understands.

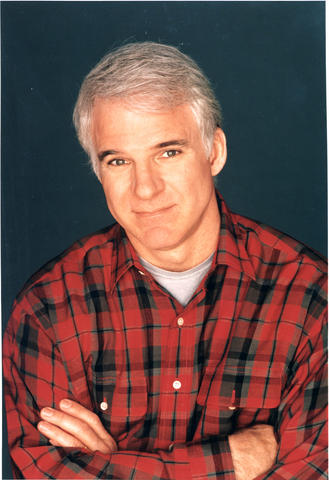

PHOTO: AP

What Martin does best is a combination of schmaltz and satire, and it has its roots in a childhood spent wandering around Disneyland. The most vivid scenes in the book are the early ones, in which the 10-year-old Martin scores an after-school job selling guide books at a theme park that opened a few kilometers from his home in California in 1955. It entitled him to free rides and provided him, if one is minded to look at things this way, with an almost mythological basis for a career in showbiz. For the next eight years he worked in the park in one capacity or another, finding an eventual home demonstrating tricks in Merlin's Magic Trick Shop. This suited his disposition exactly. He spent hours in his room, practicing his act, keeping a notebook in which he reviewed his performances with agonized sincerity.

He is still obsessed with the theme park of that era, going online to find old snapshots of the place, and its appeal was probably amplified at the time by its contrast with his home life. A nuclear silence pervaded the Martin household; his father was a bully, his mother supine in the face of it, and Martin was desperate to get out. He diagnoses his father's problem as being one of disappointment: he'd wanted to be an actor but ended up in real estate and took it out on his son. There's a scene in the book in which his father takes umbrage at something Martin says at the table, leans across to clout him and gets carried away and beats him up. It happened only once, but the incident looms large in Martin's imagination, surfacing in his second novel, The Pleasure of My Company.

By the time Martin was 18, his magic act was good enough to appear before a paying audience, at a local theater called the Bird Cage. It was morphing into a combination of tricks, banjo-playing and joke-telling by then. At some point he realized that the magic tricks were funnier if they didn't work. His comedy, he decided, was not comedy so much as "a parody of comedy."

"I was an entertainer who was playing an entertainer," he writes in the book, "a not so good one." He told jokes without punch lines that left the audience puzzled and sang songs with corny tunes that included words such as "obsequious" and "geology." Martin says now, "Only looking back did I realize that what I did was completely fabricated."

This sounds like a strange kind of modesty. Isn't everything in showbiz fabricated?

"I guess I'm talking about natural talents," he says. "What I mean is that none of my talents had a - what's that great word - rubric. A singer, an actor, a dancer - there was nothing I could really say I was. The writing came much later. And, actually, thank God, because if I had said I'm a singer, I would really have just had one thing to do. But stand-up comedy was a synthesis of various things I did. So I said, OK, I guess that's what I am."

For a while, he thought about doing a doctorate in philosophy and becoming a teacher. But the pull of the comedy clubs was too great. Photographs of Martin from that era are startling: he went gray young, as had his parents, and it never bothered him, he says, though for a short while in his 20s he had a Kris Kristofferson-style bouffant and beard. His experience of the 1960s was mostly disastrous. He had a panic attack after smoking dope one night and had to leave a movie theater in the middle of the film, the upshot of which was that he never took drugs again. He nearly had an affair with Linda Ronstadt, but was so intimidated by her that after a couple of outings she said to him, "Steve, do you often date girls and not try to sleep with them?" He toured the country with his comedy act, every night in a different city, and was lonely and depressed. He was pursuing what he calls a "wrong-headed quest for solitude."

I ask what he means by that. "I think I meant that, given the circumstances of my childhood, I had the illusion that it's easier to be alone. To have your relationships be casual and also to pose as a solitary person, because it was more romantic." He was also, he says, "very shy. So maybe it's just a cover for your insecurity."

Success, when it eventually arrived, didn't do much to fix this. He started landing TV spots on Johnny Carson and Saturday Night Live, won an Emmy as part of the writing team on a TV show called The Smothers Brothers, and then in 1977 his comedy album, Let's Get Small, sold one and a half million copies. After more than a decade of hard graft, he could suddenly command live audiences of up to 22,000 people. Clips of those shows are still funny.

He had always been commercially savvy; when every other 1960s comedian was dressed as a hippy, he wore a suit and tie. He realized pretty quickly that if he was to have a long-term career, he should use his profile as a stand-up to try to get into the film business. Looking back, he's proud of the lean years in a way that suggests he is still, essentially, a romantic. One of his favorite parables is Brer Rabbit. "The rabbit is caught by the hunter," Martin says, "and says to him, 'Please, please, whatever you do, don't throw me in the briar patch.' And he convinces the hunter to throw him in the briar patch because it's the worst possible thing that could happen to him. So the hunter throws him in the briar patch and the rabbit laughs and says, 'I was born in the briar patch,' and scampers away."

It is one of Martin's great regrets that his parents never understood his work. He suspects they were embarrassed by "all this absurd, silly comedy, with dirty words sprinkled here and there." After the premiere of The Jerk, he went out to celebrate and one of his friends said to his father, "You must be very proud." And his father replied, "Well, he's no Charlie Chaplin."

By today's parenting standards, this would be practically cause for arrest. "Yeah," he says, "today most parents say to their kids, 'I can't believe how great you are.' I think that it was kind of naive on his part."

The kind of father Martin plays in Parenthood and its lesser imitations, Father of the Bride and Cheaper By the Dozen, is the soppy modern kind and is why audiences regard him with such warmth. For 10 years he was married to the English actress Victoria Tennant, with whom he appeared in LA Story. They divorced in 1994. Earlier this year he married Anne Stringfield, a writer, who is 34 to his 62, and so the question of whether Shopgirl, his novel about a young woman who falls for a man twice her age, was based on their relationship is an obvious one. Martin doesn't welcome it. "Not entirely," he manages.

It's a curious book, full of people making small gestures that denote vast psychological movements, and as the narrator Martin comes across as the sort of guy who takes pride in being a man who understands women - the heroine is at one point discovered to be "bearing her anguish so solitarily" and is said to be "aware of every incoming sensation that glances obliquely against her soft, fragile core" - a sentence so dank it's one stop short of describing the influence of the moon on "female behavior." Martin says his aim was to write about relationships as they really are, but as he lusts after Claire Danes' soft, fragile core in the film version, all you can think is: ugh, midlife crisis fantasy.

It may be that audiences simply can't accept Martin in anything other than his traditional comic role. He doesn't have children, and so I wonder if it strikes him as strange that this image of him as America's favorite dad predominates.

"It's funny but I don't think that about myself. I think I did some age-appropriate father roles - well, I was a little too old, frankly" - he laughs - "but I never thought I'm going to make that my thing. I'm not an action star, so I can't be a guy out there with a gun." In his 30s and 40s, he found a lot of the scripts that came his way boring. "You know, the guy-who-always-treated-women-badly-but-now-falls-for-someone-and-learns-his-lesson. The characters are so stereotyped."

He doesn't like gross-out comedies, either. "I wouldn't want to do a movie that is just an assault on your senses." And while he thinks Sacha Baron Cohen's Borat is great, "The lower practitioners of [that genre of comedy] are really cruel - prank phone calls," he says. "Of course you can call up an old lady and lie to her on the phone and make her feel stupid. Of course you can. But I thought Borat was a breakthrough comedy, because it was really funny. It wasn't some studio-produced script with 14 writers."

The films he said yes to were ones that "did what early films did to me: they affect people, even at a sentimental level, and I don't mean that in a negative way." Planes Trains and Automobiles, in which he co-starred with John Candy as the dad trying desperately to get home in time for Thanksgiving, is what he calls a "good sentimental film. Listen, I would love to be in a fabulous art film, or a mystery but I'm not known for that, and people can't quite ... I affect the movie negatively, I think."

In 1993, Martin wrote a play called Picasso at the Lapin Agile, an imagined meeting between Einstein and Picasso in a Paris bar in 1904. It's the only thing his father straightforwardly congratulated him on. "I tried to figure out why, and I think it was because it was in an area in which he had no ambition." Ouch. Martin's other straight dramas have had mixed results. After The Jerk he made Pennies From Heaven, a film version of the Dennis Potter drama that was, he says, "audience-jarring," and he wishes now that he'd made The Jerk 2. "But by then I was tired of my own persona. I just couldn't do it. And Pennies From Heaven gave me a great gift of having my time completely occupied, learning to dance. Class every day, hours and hours and hours, and there was no time to over-think."

These days, he channels his over-thinking into novel writing. The Pleasure of My Company is much better than his first novel. It's told from the perspective of a man with an obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Martin understands a little of this from his days obsessively rehearsing his magic tricks.

For 10 years or so, Martin informally studied psychology in a way that puts one in mind of this character. He read books on the subject and would question his friends intensely about how they came to be the way they were. "I was always very interested in how people broke up. If I ever hear about people having affairs, I really get interested in exactly what's done and what's told." The conclusions, if that isn't too formal a word for them, reveal an acquired optimism in Martin's nature and also a release from all those years of bad relationships and blaming his dad.

"Let me tell you a story," he says. "I had two female friends. One was extremely outgoing - she lit up a room when she walked in and was always talking and laughing. And I have another friend who is very shy and doesn't want to upset people - you know, 'Did I offend you? Did I hurt you?' Both very likeable, but opposite personalities. And I asked the outgoing one, I said, how did you become this way? And she said, well, when I was a kid, my parents just loved everything I did. Everything I did they said, 'That's fabulous, you're so great,' and I felt so confident. And to the shy one I said, how did you become this way? And she said, 'Oh, when I was a kid my parents just loved everything I did and I didn't feel inspired to do anything else."

Martin's father died in 1997 and his mother in 2002. Both death scenes as he describes them in the book are extraordinary. They are quoted verbatim. On his death bed his father expressed regret for "all the love I received and couldn't return," and told his son, "you did everything I wanted to do." Martin replied, "I did it for you," and in the book adds, "I was glad I didn't say the more complicated truth: "I did it because of you." While she was dying, his mother said, "I wish I had been more truthful," by which Martin took her to mean she wished she had stood up to his father's silent tyranny. "I wanted to remember those words always," he says, "because they were so moving. They were untranslatable. You couldn't paraphrase those sentences and have the same power."

Born Standing Up, by Steve Martin, will be published next week by Simon & Schuster.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the