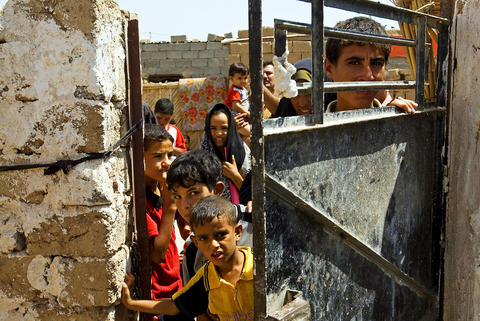

The number of Iraqis fleeing their homes has soared since the American troop increase began in February, according to data from humanitarian groups, accelerating the partition of the country into sectarian enclaves. Despite some evidence that the so-called troop surge has improved security in certain areas, sectarian violence continues and American-led military operations have brought new fighting, driving fearful Iraqis from their homes at much higher rates than before the tens of thousands of additional troops arrived, the studies show.

The data track what are known as internally displaced Iraqis: those who have been driven from their neighborhoods and seek refuge elsewhere in the country rather than fleeing across the border. The effect of this vast migration is to drain religiously mixed areas in the center of the country, sending Shiite refugees toward the overwhelmingly Shiite areas to the south and Sunnis toward majority Sunni regions to the west and north.

Though most displaced Iraqis say they would like to return, there is little prospect of their doing so. One Sunni Arab who was driven out of the Baghdad neighborhood of southern Dora by Shiite snipers said she doubts that her family will ever return to the house.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

"There is no way we would go back," said the woman, 26, who gave her name only as Aswaidi. "It is a city of ghosts. The only people left there are terrorists."

Statistics collected by the Iraqi Red Crescent Organization, indicate that the total number of internally displaced Iraqis has more than doubled, from 499,000 to 1.1 million, since the start of the surge in February.

Those figures are broadly consistent with data compiled independently by an office within the UN that specializes in tracking wide-scale dislocations. That office, called the International Organization for Migration, found that in recent months the rate of displacement within Baghdad itself, where the surge is focused, has increased by a factor of as much as 20, although part of that rise could stem from improved monitoring of displaced Iraqis by the government in the capital.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The new findings suggest that while sectarian attacks have dropped in some neighborhoods, the influx of troops and the intense fighting they have brought with them is at least partly responsible for what a UN migration office report calls the worst human displacement in Iraq's modern history.

The findings also indicate that the sectarian tension the troops were meant to defuse is still intense in many places throughout the country: 63 percent of the Iraqis surveyed by the UN said they fled their neighborhoods because of direct threats to their lives, and over 25 percent because they had been forcibly removed from their homes.

The demographic shifts could favor those who would like to see Iraq partitioned into three semi-autonomous regions: a Shiite south and a Kurdish north sandwiching a Sunni territory in between.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Overall, the scale of this migration has put so much strain on Iraqi governmental and relief offices that some provinces have refused to register any more displaced citizens, or will accept only those whose families are originally from the area. But Rafiq Tschannen, chief of the Iraq mission for the migration office, said that in many cases, the ability of extended families to absorb displaced relatives was also stretched to the breaking point.

He also cautioned that reports of people going back to their homes were overstated. As the surge began, the Iraqi government said that it would take measures to evict squatters from homes that were not theirs and make special efforts to bring the rightful owners back.

"They were reporting that people went back, but they didn't report that people left again," Tschannen said. He added that Iraqis "hear things are better, go back to collect remuneration and pick up an additional suitcase and leave again. It is not a permanent return in most cases."

American officials in Baghdad did not return requests for comment, but the national intelligence estimate released on Thursday confirmed that Iraq continues to segregate through internal migration. "Population displacement resulting from sectarian violence continues," it found, "imposing burdens on provincial governments and some neighboring states."

Said Hakki, director of the Iraqi Red Crescent Organization, said that he had been surprised when his figures revealed that roughly 100,000 people a month were fleeing their homes during the surge. Hakki said that he did not know why the rates were so high but added that some factors were obvious.

"It's fear," Hakki said. "Lack of services. You see, if you have a security problem, you don't need a lot to frighten people."

It is clear that military operations, both by American troops and the Iraqi forces working with them as part of the surge, have something to do with the rise in displacement, said Dana Graber Ladek, Iraq displacement specialist for the migration organization's Iraq office.

"If a surge means that soldiers are on the streets patrolling to make sure there is no violence, that is one thing," Ladek said. "If a surge means military operations where there are attacks and bombings, then obviously that is going to create displacement."

But Ladek added that in contrast to the first years of the conflict, when major American offensives were a major cause of displacement, the primary driving force has since changed.

"Sectarian violence is the biggest driving factor - militias coming into a neighborhood and kicking all the Sunnis out, or insurgents driving all the Shiites away," Ladek said.

Her conclusions mirrored the experiences of Iraqis who have fled their homes in Baghdad and elsewhere.

Aswaidi and her family left Dora section of Baghdad five months ago when Shiite snipers opened fire on their Sunni neighborhood from nearby tower blocks.

Returning covertly to check on the property in mid-August, she found Sunni insurgents occupying the building and neighboring homes, walking unchallenged through the deserted streets.

She now fears that her entire neighborhood will be taken over by Shiite militias like the Mahdi Army, which is loyal to the radical Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr.

"I don't want them to take my town, but I think they will," Aswaidi said. "It will change from Sunni to Shiite. The Americans can't stop it."

Shiites face similarly overwhelming odds. In Shualah, on the northern outskirts of Baghdad, 400 Shiite families now live in a makeshift refugee camp on wasteland commandeered by al-Sadr's followers.

In a sprawl of cinderblock hovels and tin and bamboo-roofed shacks, families have stories of being expelled from their homes by Sunni insurgents.

"It is still an unsafe area," said an unconvinced Edan.

Both humanitarian groups based their conclusions on information collected from the displaced Iraqis inside the country. The Red Crescent counted only displaced Iraqis who receive relief supplies, and the UN relied on data from an Iraqi ministry that closely tracks Iraqis who leave their homes and register for government services elsewhere.

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,