Science fiction is dead. Long live science fiction.

For those of us who care (and no, we do not live in our parents' basements), the future of futurism is an urgent matter indeed. Is science fiction thriving amid the pyrotechnics, or is it dying a slow and hideous death, suffocated by publishing-industry group-think and unimaginative movie execs drunk on sequels?

I speak as a fan with opinions - as though there's any other kind - when I pronounce the sound health and shining future of 21st-century speculative fiction. I'm less concerned with the release this month of the megabudget Transformers movie, with its gargantuan alien robots and shiny cast, than a prevailing cultural shift that seems to embrace the expansive narrative frontiers of sci-fi. And I'm not even counting the genre's recent successes on television (Battlestar Galactica, Heroes, The 4400, Lost) or world-domination in games (take your pick).

PHOTOS: AFP

"It's everywhere now. Everybody has some exposure to it - it's much more respectable than it used to be," says David Wellington, a sci-fi/horror author (Monster Island, Thirteen Bullets) and aficionado who recalls the bad old days of fandom. "Back in the 80s, when I was a huge science-fiction fan, it was very marginalized. And we always complained about that: 'Why can't other people understand why we like this stuff so much?'"

Wellington is one of several devotees who, given the chance to vent, expresses enthusiasm as well as skepticism at the current state of the genre. Many view the landscape ahead with caution, fearing a post-apocalyptic vista mottled by computer-giddy graphics and the blunt force of mainstream taste. Some see it fragmenting. Others see it thrive.

But fans reach consensus - sort of - on a few key issues. One is that fantasy novels, once joined at the hip with science fiction, have enjoyed huge success since venturing into their own sizable niche. A second is that the film and publishing industries should take more artistic risks. A third: Blade Runner rocks. Fourth: so do Pan's Labryinth and Children of Men.

Exciting Times, Visually

A fifth point, expressed with varying degrees of disappointment and annoyance, is that advances in digital technology have made for gob-stopping eye candy that doesn't always satisfy the mind or the heart. From a visual standpoint, "there's no better time in the history of films for science fiction," says Dave Dorman, an in-demand sci-fi/fantasy painter based in Florida best known for his Star Wars renderings. "On the other hand, I think the writing of science-fiction films is not up to what it was back in, say, the 40s, 50s and 60s."

Craig Elliott, an animator for Disney (Treasure Planet) and DreamWorks (the upcoming The Princess and the Frog), puts it even more succinctly: "There's too much bling on the screen."

In publishing, contemporary science fiction has splintered into a zillion little sub-sets, running from alternate history and space opera to hardcore, urban fantasy, movie and TV tie-ins, cyberpunk and the boundary-stretching "New Weird."

Call it what you will, but great science fiction can be cosmic or minimalist, outward-looking or inward. It expands or contracts, pushing humanity into the farthest reaches of space or reducing it to cinders.

From the start, it's never been about the rubber-faced aliens, not really. Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland (written in 1884 and adapted repeatedly for film) is set in a two-dimensional world that skewers Victorian class distinctions. H.G. Wells and Jules Verne both injected the acid of satire into the pulp of sci-fi, and even the dated strangeness that is Karel Capek's R.U.R. (or Rossum's Universal Robots, the play that coined the word) was more concerned with sentience and civil rights than the construction of humanoid workers.

Do we watch Fritz Lang's Metropolis for the sexy android, or the Marxist parallels? Is The Day the Earth Stood Still about a guy in a soup can or a world poised on self-destruction? Sci-fi can offer visions of a humankind freed from poverty, racism and the horrors of war (see Star Trek's first two series) or ravaged by violence in a post-nuclear wasteland (Mad Maxes one through three). You can feel good or bum out, depending on your mood.

Lately, a lot of folks are bumming. During the past few years dystopian yarns have surged in popularity, prophesying tomorrows wracked by terrorism (V for Vendetta), zombie germs (28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later) and infertility (Children of Men). All three of those films are set in London, the new vogue setting for ashen pessimism.

In literary fiction, Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go moved dystopia to the English countryside. Margaret Atwood moved it stateside (The Handmaid's Tale, Oryx and Crake), while Cormac McCarthy pushed it even farther with The Road. Not everyone calls his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel science fiction, but that's what it is: Man and boy wade through the soot of an annihilated landscape.

Sci-fi/fantasy marketer and publicist Colleen Lindsay has high praise for McCarthy's book, but she's vexed by the perception that it's anything new. "It's post-apocalyptic fantasy for people who don't read fantasy." Look at David Brin's The Postman and S.M. Stirling's Dies the Fire, she says: similar books written by (gasp) genre authors and read by (gasp) geeks. Or consider Richard Matheson's classic 1954 I Am Legend, the original zombie-germ novel, adapted to film in 1964 (The Last Man on Earth), 1971 (The Omega Man) and now 2007 (I Am Legend, scheduled for the end of this year).

Kfir Luzzatto, a science-fiction author who lives in Israel, mentions John Christopher's The Death of Grass (1956) and Mary Shelley's The Last Man (1826), which foresees a late-21st century devastated by plague. "Post-apocalyptic culture has become to modern people what ghost stories were to our fathers," he says. "(It's) a way to air your fears of the unknown and to deal with them."

On the flip side, the more gung-ho element of sci-fi continues to pit good against evil, and good continues to win - after an extremely noisy fight. Consider those Transformers. "Do we believe that we're alone in this constant struggle, or do we believe that we can help each other?" asks Jamie Hari, who founded and runs the Marvel Database Project out of Toronto. Hari, who says "Marvel is my world" without embarrassment, sees the appeal of Transformers and robots in general "as another extension of the human desire for technology."

Pooping insects

A figure well familiar with this idea is Lawrence Krauss, a professor of physics at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and the author of The Physics of Star Trek. If you watch How William Shatner Changed the World, he's the one making pizza with the Shat.

"People like the idea of a hopeful future," Krauss says, later admitting that "the utopian view is harder for me to believe." Generally, the genre grabs his attention when it's smartly done but lost him at Starship Troopers: "The pooping insects, that sort of did it for me."

Otherwise, he says that science, like art, considers our place in the cosmic scheme. "The reason that we're scientists is not because we want to build a better toaster," he contends, "but because we're interested in what's possible in the universe."

Judging from anticipated movie releases, this is what's possible in the universe. Earth might be invaded by alien body snatchers (Invasion). It might face planetary death from a dying sun (Sunshine). It might be torn by global terrorism (Day Zero, upcoming). It might, in the field of engineering, produce super-powered exoskeletal armor (Iron Man, 2008), or it might form intergalactic relations with pointy-eared ET's (Star Trek, 2008). Alternately, a race of tiny aliens might tour the cosmos inside Eddie Murphy, who might then fall in love with an Earth babe (Starship Dave, 2008).

All of this looking forward strikes Houston's John Moore, an "unrepentant geek" and sci-fi/fantasy author (A Fate Worse than Dragons), as old news. "Science fiction is the present. We live in a science-fiction society, and I don't just mean the gadgetization of society." Instead, he means that "projecting into the future, once the province of the science-fiction writer, has become our dominant way of thought."

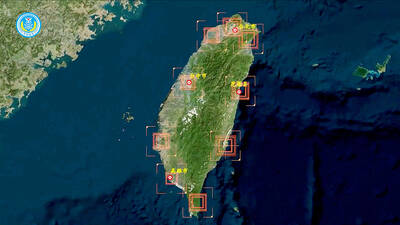

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by