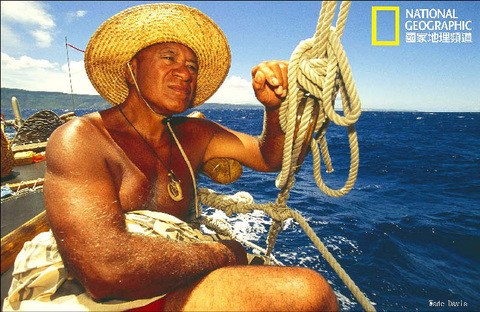

Wade Davis has, perhaps, the world's most fascinating job. The "Explorer in Residence" at the National Geographic Society has spent the past few years making four documentaries that have seen him journey through the hard biting snow of the Arctic to join an Inuit polar bear hunt, participate in the ancient Polynesian navigational art of Wayfinding, celebrate an ancient ritual with the indigenous people of Peru and seek the secrets of enlightenment on the mountains of Nepal. For Davis, adventurer extraordinaire, it's all in a day's work.

The four-part documentary, called Light at the Edge of the World will premier tomorrow at 9pm on the National Geographic Channel.

Working for an organization that, over its hundred-year existence, has brought some of the remotest cultures into the world's living rooms, is a mission that Davis holds close to his heart. Yet, like Davis, the National Geographic Society's mission has undergone considerable change over the past few years.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCETY

"What is [National Geographic's] mission today?" Davis asks. "Our board ... concluded that if its mission in the first 100 years was to tell you about the world, the society's mission in the next 100 years will be to save the world."

National Geographic's transformation from educator to protector of distant cultures parallels the career change of the Canadian-born and Harvard-educated Davis (he holds degrees in biology and anthropology and received his PhD in ethno-botany), who made the leap from hard-hitting academic to conservationist.

"I felt the issues I'd been studying in my academic training as a botanist and as an anthropologist in terms of biodiversity and cultural diversity were simply too important to be left within the constraints of the academy," he said when asked why he made the switch.

"No biologist would suggest that 50 percent of all species is on the brink of extinction because it simply isn't true. And yet, that ... pessimistic assessment in biological diversity hardly approaches the most optimistic assessment in cultural diversity."

Davis' concerns for the threatened indigenous populations throughout the world, as well as his travels and his studies of plants and indigenous cultures, has made him a powerful spokesman for cultural conservation.

"We embrace conservation in all its manifestations: conservation of the oceans, forest and biodiversity, conservation of archaeological sites and critically ... the conservation of our own legacy."

By legacy, Davis means the whole gamut of human civilization of which he says language is the clearest manifestation. And with fully half of the world's languages threatened with extinction Davis says there is an ever-greater urgency to protect them. "Every two weeks on average some elder passes away and carries with them into the grave the last syllables of an ancient language," he says.

Death of diversity

Through his work on the documentaries and his discussions with scientists throughout the world, Davis identifies two fundamental reasons for the erosion of cultural diversity.

The first is the notion that indigenous peoples are primitive and lazy, the ideological underpinnings of which can be traced back to theories of race, such as 19th-century Social Darwinism, that placed white European society at the top of the intellectual ladder and Aboriginals at the bottom.

This idea, which Davis calls "one of the greatest intellectual lies of history," was of course proven wrong by advances in genetic technology that showed that all humans are cut from the same genetic cloth. The corollary of this truth — an insight Davis feels isn't highlighted enough — is that intellectual creativity is a matter of choice.

"Whether genius is putting a man on the moon — in a way the greatest technological achievement of the West — or the Tibetan Buddhist tradition [of] understanding the nature of mind over a 2,500 year intellectual pursuit of the nature of existence is simply a matter of choice and cultural orientation," he said.

As historical and ideological issues have yet to be fully addressed, it has led to the other, more contemporary, problem of governmental policy that emphasizes economic expediency over the preservation of culture.

"Today the forces affecting culture are many: it can be ill-conceived development plans that encourage nomads to settle down because they are perceived to be an embarrassment to the nation state. It can be ill-conceived acts of industrial developments or deforestation of the homeland of forest people, or mining developments that impact the health of rivers upon which people depend."

Davis says that in every case, indigenous people are being driven to extinction by identifiable forces. "And that's actually a very optimistic observation because it suggests that if human beings are the agents of cultural destruction, we can be the facilitators of cultural survival.

Davis fears that the continued reluctance of governments to make culture a fundamental part of their policy is leading to a less stable world.

"When people lose the comfort of tradition and feel these kinds of pressures of intense change that can provoke a sense of disappointment, disaffection, alienation, you get very strange movements emerging that can be very dangerous. Al-Qaeda is one of these kinds of fantasy movements that invoke a world of Islam that never existed but has to be presumed to have existed for those who are trying to rationalize the humiliation of all these years of chaos in the Middle East. Maintaining the integrity of culture is not an act of sentimentality; it's not an act of nostalgia, its much more than an act of human rights. It's about maintaining the integrity of civilization itself," he said.

Falling on deaf ears

But are politicians and the media listening? Davis doesn't think so. He cites, for example, in the immediate wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on the US, a meeting of 4,000 anthropologists from the American Anthropological Association was held in Washington DC where the primary topic of discussion was the attack on the Twin Towers.

"The entire gathering earned a single line in the Washington Post, in the gossip section, that basically said 'the nut cases are in town,'" he said. "And who is more remiss: the government for not having the ability to listen to the one profession that could have explained what was going on or the profession for not having the ability to communicate effectively with the world at large?"

It is these kinds of questions Davis hopes to address as Explorer-in-Residence at National Geographic.

"How do we find ways to ensure that all peoples choose the components of their lives and also benefit from the genius of the modern world without that engagement having to demand the death of their ethnicity or who they are?" he asked.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and