All bets are off. Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is going to win the 2008 presidential election, if he enters the race. At least that's what David Lin (林大為) said after analyzing the auspiciousness of possible candidates' names including Frank Hsieh (謝長廷), Su Chen-chang (蘇貞昌), Wang Jin-ping (王金平) and Ma.

"The composition and structure of [Ma's] name shows ... the year of the election will be very good for [him]," said David Lin, CEO of Veryname.com (非常姓名網). "It's the name of a politician rather than a salesman."

Though Ma will probably have difficulty selling his platform to voters in the south, Lin said as the election draws nearer his luck will improve. What can the other candidates do? Change their names and their luck, perhaps.

PHOTO: NOAH BUCHAN, TAIPEI TIMES

Employing a fortune-teller to choose a new name is a common practice. Surnames are rarely changed because of their importance in maintaining the family lineage. Sometimes a person will change their given name because of its negative phonetic association, while others are embarrassed by their given names.

If the first-born child was a girl, it was common up until the 1970s for parents to give her the name zhaodi (招弟) — literally meaning "invite younger brother," which indicated a preference for male children.

According to the most recent statistics from the Department of Household Registration Affairs, 172,654 Taiwanese changed their names in 2005, about 15,000 less than 2004, but a jump of 68,000 since the office starting monitoring name changes in 1997. According to the Name Act (姓名條例), Taiwanese citizens can only change their name once, though if unsatisfied with a new name the law allows reversion to the birth name.

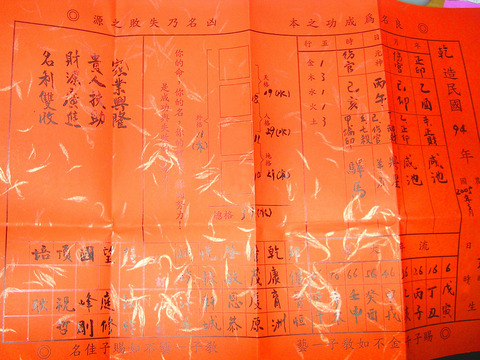

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CHAN QI-ZHEN

Chan Qi-zhen (陳琦臻) was going through a rough patch. With a recent divorce, two young children and poor job prospects she decided that a change was in order.

She visited a fortune-teller at Ciyou Temple (慈佑宮) who analyzed her name and listed all the problems she was facing. Shocked by the woman's accuracy, Chan agreed to have the fortune-teller choose her a new name.

"I'm not a superstitious person," Chan said. "[But] after the failure of my marriage, I thought that maybe there was something wrong with my fortune."

Chan's father chose her original name which means intelligence and cleverness. According to the fortune-teller, however, Chan's given name also made her aggressive, which influenced her personal affairs and reduced her job prospects.

Before meeting the fortune-teller, Chan had found a new name by searching through dictionaries. But, according to the woman at the temple, the name Chan chose was inappropriate.

After paying NT$500, the fortune-teller gave Chan a list of names, from which she chose one. Rather than picking the name immediately, Chan invited her friends to offer their opinions and after all the votes were cast the most popular name was adopted.

Lin Yu-teng (林宇騰) changed his name for different reasons.

Having reached 45, he felt a sense of powerlessness in his life and job. When he saw a fortune telling master on television espousing the effectiveness of name changing as a means of improving a person's prospects, Yu picked up the phone.

Five-minutes of calculations and NT$3,000 later, the disciple provided him with eight characters in two rows, of which he would select one from each.

"The name I eventually chose means that I'll have a good reputation, good fortune and good health," he said.

David Lin said women generally change their name for family or household reasons, but males usually cite career concerns for making a switch.

Born into a family of fortune-tellers, David Lin has earned a reputation for having considerable knowledge of the significance of names. With 1.5 million registered members on his Web site, in addition to other fortune-telling services Lin's site offers name changing services for NT$700. For in-house name changing services, he charges up to NT$10,000.

Business is booming with around 1,000 new members signing up each month over the past year.

But fortune-tellers are not the only ones providing new names to the unlucky. On rare occasions, gods will grant an auspicious name to those in need. Taipei resident Lin Hsien-chien (林新建), 32, said that when he was younger he his health was poor. His mother prayed to the deity Matzu to provide him with a new name. Her prayers were answered.

"It just came to her. She started writing down the name, as if in a trance," Lin Hsien-chien said.

Is changing name jiggery-pokery or a road to good fortune?

"It's hard to say that the changes in my life can be attributed only to changing my name," Chan said, "but I can feel that my emotions have become more stable. I now feel happier and open-minded."

Lin Yu-teng offers a different perspective: "[Changing names] can only be 20 percent [effective]" because a person's fate is fixed at birth and it can be altered slightly. "But I feel that changing my name improved by [job] position."

Yeh Chuen-rong (葉春榮), an associate research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, says name changing is an integral part of the system of cosmological beliefs in Taiwan.

"[Taiwanese] have a different cosmology than the West. That is why they do these kinds of things. Even though Westerners know there are uncertainties, [they] don't try to decipher these secrets through names," Ye said.

There is no scientific basis for the existence of a Chrisitan god, Ye said, but many still believe because it gives them hope for the future.

Chan believes changing her name meant starting her life over.

"Now, I really feel strange and unfamiliar with my old name," she said. "But, I am not so sure that my sentimental transition came from my name change or the passing of time."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the