Feminine beauty has been celebrated across the ages, but an enduring belief is this: what constitutes attractiveness in a woman cannot be pinned down — it depends on the prevailing fashion, culture or ethnicity and on the eye of the beholder.

For instance, in Victorian England, a tiny, puckered mouth was the zenith of pulchritude.

Today, the rosebud look has been replaced by what has been called the trout look, as women in Western cultures strive to make their mouths look as wide and full-lipped as possible.

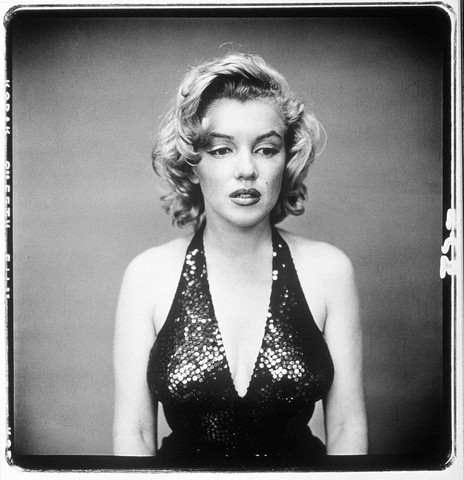

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

In many societies, the focus of secondary erogenous zones has roamed over ankles, necks and knees and makeup and hairstyles change according to the mode.

The desired female morphology has shifted too, driven in part by prosperity and the social advancement of women. In the 1950s, Marilyn Monroe was the template of feminine beauty; today, she would be encouraged to sign up at Weightwatchers.

So it would seem that the "beauty standard" does not exist — that there is no eternal benchmark, only a chaotically whizzing merry-go-round.

Not so for evolutionary psychologists.

For them, fashion is a fluffy cover for a force that is deeper, remorseless and unchanging, as old and enduring as our genes: the Darwinian drive of survival and genetic fitness.

In an innovative test of these rival hypotheses, scientists at the University of Texas at Austin and at Harvard University trawled through three centuries of English-language literature and through three Asian literary classics dating back nearly two thousand years.

Their goal: Which parts of the woman's body were praised as beautiful by writers across the ages?

Their sources were a Web site, Literature Online, for English literature from the 16th, 17th and 18th century; Chinese sixth dynasty palace poetry (from the fourth to the sixth century AD) and two ancient Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, from the first to third century AD.

Breasts, buttocks and thighs — the primary erogenous zones — predictably featured large in these descriptions.

But a slim waist trumped them all.

In English literature, a glowing description of a narrow waist (a waist "as little as a wand", "beholden to her lovely waist" and so on) showed up 65 times.

That compared to 16 references for romantic description of breasts, 12 for thighs and a mere two apiece for hips and buttocks.

Before anyone cries fattism, the literature was studded with romantic tributes to plumpness but relatively few to slimness.

But what counted, plump woman or slim, was the relative narrowness of the waist. There was not a single evocation of beauty that said the object of veneration had a bulging tummy.

In the Asian works, the slim waist was even more adored, although there was no flattering reference to plump beauty.

Narrow waistedness scored a massive 35 references in the two Indian epics, while the other body parts garnered a total of 26. In the Chinese poetry, the narrow waist was evoked 17 times, while breasts, buttocks, hips and thighs got zero, and there was a solitary romantic reference to a woman's legs.

The study, which appears in Proceedings of the Royal Society, a British journal, says these references show that a slim waist is an object of desire that spans time and cultures.

Why so?

The answer, suggest the authors, is that a narrow waist is a sign of strong health and fertility. Men instinctively assess a woman's waist for its potential for successful reproduction and thus furthering their own genes.

Modern research has established a link between abdominal obesity and decreased estrogen, reduced fecundity and increased risk of major diseases.

But "even without the benefit of modern medical knowledge, both British and Asian writers intuited the biological link between health and beauty," say authors, Devendra Singh, Peter Renn and Adrian Singh.

"In spite of variation in the description of beauty, the marker of health and fertility— a small waist — has always been an invariant symbol of feminine beauty."

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of