Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall: An Artist's Country Estate is the rare exhibition that comes with its own porch. And not just any porch. The Daffodil Terrace temporarily installed at the Metropolitan Museum is larger than many Manhattan apartments. Its tall marble columns are topped with clusters of yellow flowers — daffodils — made of blown glass, the material in which Tiffany achieved his greatest eloquence.

Reassembled here for the first time since Laurelton Hall burned to the ground in 1957, the Daffodil Terrace adds a fitting Temple of Dendur splendor to a strange and lovely exhibition. It has been organized by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, the Met's curator of American decorative arts, and presents a series of beautiful objects in search of a ghost.

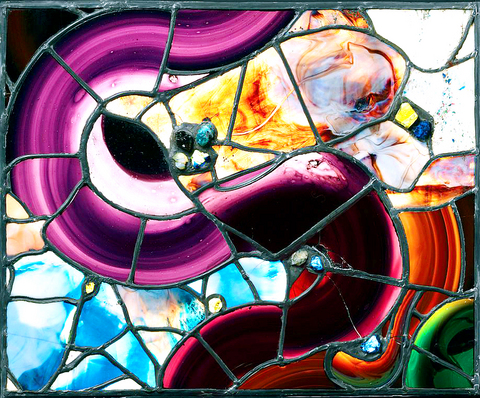

The Daffodil Terrace once connected the dining room and the gardens at Laurelton Hall, the grand estate that Tiffany built for himself from 1902 to 1905 on 580 extensively landscaped acres overlooking Long Island Sound. It is displayed here in an enormous gallery, along with the stained-glass windows whose trailing wisteria vines brought the garden into the dining room, and the imposing white marble mantel whose three glass mosaic clocks let diners keep track of the time, the day and the month.

PHOTS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Tiffany was born in 1848, the industrious son of a wealthy founder of the luxury-goods business soon known as Tiffany & Co. He set out to be a painter, touring Europe and the Mediterranean and becoming especially smitten with Orientalism. But he had more facility than originality, as the paintings and watercolors here attest.

An inveterate shopper and cultural scavenger, he must have realized that his love of the exotic — Egyptian, Persian, Asian and North African — might be best expressed in objects, and that these objects could be orchestrated into seductive living environments that no painting could match.

By 1875 Tiffany was spending time in Brooklyn glasshouses, learning the craft. By 1885 he was in the process of melding the English Arts & Crafts notion of the unified interior and the Aesthetic Movement's love of eclecticism into an encompassing vision of his own that presaged Art Nouveau.

He oversaw a succession of companies and factories where as many as 300 artisans produced leaded-glass windows and lamps; favrile-glass vases made by a technique of his own invention; all kinds of objects in enamel and carved wood; and textiles, furniture and rugs. With these resources Tiffany designed lavish multicultural living quarters for the richest, most adventuresome figures of the Gilded Age, including the collectors H.O. and Louisine Havemeyer.

Had Laurelton Hall survived, it would have been Tiffany's ultimate work of art, a monument to a total vision on the scale of Frederic Edwin Church's Persian-Victorian fantasy, Olana, built in the late 1860s high above the Hudson River near Hudson, New York.

In 1918 Tiffany established a foundation to maintain the estate in perpetuity as a house museum and an artist's colony. But the Tiffany Foundation fell on hard times. Although it exists today as a grant-giving body, in 1946 it auctioned off the contents of the house, divided the property into parcels and sold those too. The new owners of the main house rarely visited.

Within days of the fire and at the Tiffany family's request, Hugh F. McKean, an artist who had received a residency at Laurelton Hall in 1930, went to the smoldering ruins and pulled out anything that was relatively intact. Later he and his wife, Jeannette Genius McKean, purchased the remains of Laurelton Hall from salvagers.

These objects, including the Daffodil Terrace, became the core holdings of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida, which the McKeans had established in 1942 and named for Jeanette McKean's grandfather. In 1978 the McKeans gave the Met another Tiffany porch, Laurelton Hall's entrance loggia, which is on permanent view in the Engelhard Court in the museum's American Wing.

The exhibition gives an overwhelming account of Tiffany's talents and interests. His breakfast furniture indicates that in the early 1880s he had thoughts about simple structures and white surfaces that occurred to Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Koloman Moser decades later. There are touches of endearing modesty, like a Steinway upright piano designed by Tiffany and based on a Middle Eastern chest that seems to be inlaid with mother-of-pearl but is actually just ingeniously carved and painted.

There are also examples of Japanese, Chinese and American Indian objects that Tiffany owned, was inspired by and displayed at Laurelton Hall, including two astounding Qing dynasty headdresses made of gilded silver inlaid with brilliant blue kingfish feathers.

But the main attraction is the glass, along with the small, murky photographs of Laurelton Hall's interiors and of Tiffany's city interiors that led up to them. The show encompasses a near-retrospective of stained-glass windows, and the best reveal the different ways Tiffany translated both the gestural and the descriptive powers of painting into an altogether more tactile medium.

While Tiffany is available to us mostly in bits and pieces, objects like these seem to carry whole worlds within them.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the