For a migrant worker, Taiwan can be like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're going to get. If you're “Mary,” a 30-year-old Filipina, you might even consider yourself fortunate.

She signed a contract in the Philippines to care for an elderly woman in Taipei. Before leaving, her labor broker in the Philippines told her she had to sign a document in which she agreed to forfeit her day off. Otherwise, the broker said, she couldn't go.

Shortly after arriving here, her Taiwanese broker coerced her into signing a form stating that she owed money in the form of a loan. If she didn't sign she would be sent back.

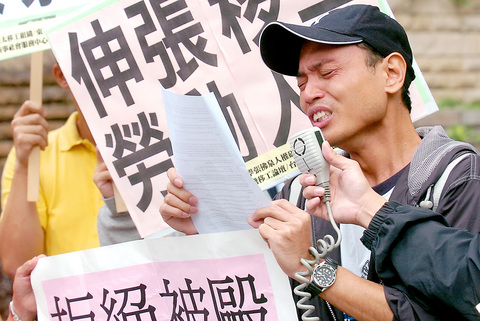

PHOTO: CHANG CHIA-MING, TAIPEI TIMES

Mary signed the form, which authorized deductions from her salary to the tune of NT$5,000 per month to pay back the “loan.” This was in addition to the standard broker's fee, which is NT$1,800 per month for the first year and decreases to NT$1,500 for the final year of a standard three-year contract.

Luckily for Mary, who was interviewed on Wednesday and asked that the Taipei Times not print her real name, the family that employs her and the Council of Labor Affairs (CLA) helped her take legal action against the broker. She was successful, and after one year the deductions stopped and the broker was forced to refund her money.

Out of gratitude for the family's help, Mary insisted, she has not complained to the authorities about being tricked into signing away her days off. But she isn't exactly happy with the way her employers treat her. In addition to caring for an 80-year-old grandmother, she's also been put to work as a full-time maid, a violation of her work permit. And the family keeps a tight watch on her movements.

PHOTO: SEAN CHAO, TAIPEI TIMES

“The brokers told me the side agreements were just a ‘formality,'” she said.

Mary's case is typical, said Liou Yen-chuan (劉彥詮), an attorney for the Legal Aid Foundation in Taipei. Liou said 90 percent of the migrant workers his office sees have been forced or tricked into signing side agreements. “There are three problems with her case, all of which are quite common. First, she's being forced to do illegal work. She was hired as a caretaker for the elderly but is also working as a maid. Second, her broker was overcharging her in the disguise of a loan. Third, she's not getting a day off,” Liou said.

He's currently helping a Vietnamese worker whose employer was deducting NT$8,000 a month from her salary in the form of a “loan.” (Foreign workers typically earn between NT$16,000 and NT$20,000 a month.) The employer has agreed to stop making the deductions, but argues he can't refund the money because he's already sent it to Vietnam.

PHOTO: SEAN CHAO, TAIPEI TIMES

Liou is confident he will get the money back. Courts generally do not uphold side agreements for “loans.” This is not the case with other side agreements, he said, especially when it comes to maids and domestic caretakers who have signed away their days off. This is because household workers are no longer protected by the Labor Standards Law, which guarantees things like maximum working hours and time off.

“It all depends on the side agreement,” Liou said.

Even though factory workers are protected under the Labor Standards Law, they too are often cajoled into forfeiting their rights by signing side agreements. When a worker signs a contract, he or she is understood as having signed onto the company's rules.

One such set of rules, for a printed circuit board manufacturer in Hsinchu, was obtained by the Taipei Times. Among the provisions is one that states that foreign workers must work overtime if they have not completed their daily quota, without extra pay. Filipinos call this “OTY,” or “Overtime, thank you.” Another regulation requires workers to hand over their passports for “safekeeping.”

A third provision states that workers who resign before their contracts expire must pay the equivalent of the salary they are owed in the remainder of their contract as a penalty.

The workers at this factory have requested that the Taipei Times not identify their company because they are considering filing a formal complaint.

Such rules are of questionable legal standing, experts say. But foreign workers are often poorly educated and isolated in their work places, which limit their movements because companies whose workers runaway face restrictions on hiring more foreign workers. According to a recent US State Department study, the government's efforts to ensure that foreigners understand their rights and know where to go for help are “modest” and “minimal.”

When a worker at a CD manufacturer in Hsinchu complained about having to pay a penalty for resigning before his contract expired, the local Hsinchu Confederation of Trade Unions and the local CLA bureau helped him win his case, according to a statement given last week by the Asia-Pacific Mission for Migrants (APMM), a Hong Kong-based group that helps overseas Filipino workers. But when several other workers at the same and another factory made the same request, the CLA told them to sort it out themselves, the statement said.

Given authorities' reluctance to aid foreign workers, strikes are sometimes seen as the only means of protesting side agreements. During one, in July last year, six Filipino workers at a Formosa Plastics refinery in Mailiao Township (麥寮), Yunlin County were allegedly beaten and forcibly sent home. Ten other coworkers were also sent back to the Philppines.

According to APMM and published accounts, the workers said Formosa Plastics tried to pressure them into signing an agreement legalizing deductions from their salaries, including an additional fee for entering the country, a Taiwanese broker's fee and a fee for their Filipino brokers.

One Formosa Plastics worker, Gil Lebria, said he was beaten unconscious, and two others were zapped with stun guns. All were forced to sign contract waivers stating that they had received their salaries and had resigned from the company — Lebria's thumbprint was forcibly used in lieu of his signature — and put on a Cathay Pacific flight back to the Philippines. Flight attendants noticed their condition and Lebria and another Filipino were allowed to stay in Hong Kong and undergo medical exams, which determined that they had been assaulted.

The Taipei Times has obtained copies of some of these documents, which bear the name of the Filipino broker, Dynamic International Services Corp, and Formosa Plastics. When contacted by a reporter, officials at Formosa Plastics in Taipei directed the reporter to their subsidiary in Mailiao. As of press time, officials contacted at the factory had not returned calls seeking comment.

There are signs that the strike in July last year paid dividends, at least after a walkout earlier this year. Previously, workers were only given a NT$4,000 allowance while in Taiwan, with the rest of their salaries wired back to banks in their home countries. Now, they receive their entire net salaries after deductions for things like health insurance and brokers' fees. This amounts to roughly NT$12,000 out of their roughly NT$20,000 base salaries.

Meanwhile, the CLA is moving ahead with reform plans, said Tsai Meng-liang (蔡孟良), the director of the council's Foreign Labor Section. These include a system where foreign workers are called to see if they signed anything under duress and, if that is the case, are provided with shelter and a chance to find another job in Taiwan. It has also proposed stricter licensing requirements for brokers and is considering ways to ease direct hiring rules so that employers can bypass brokers altogether.

The CLA has also set up a booth at CKS International Airport, where foreigners can report mistreatment before they return home. As brokers frequently accompany workers to the airport, Tsai said there are phones beyond the customs check that foreigners can also use. The number is (03) 398-3976. These services have been used 153 times so far this year.

And since 2001, brokers have been encouraged to use a voluntary affidavit, in which workers list expenses and loans owed before leaving their home countries. “We are the only country that does this,” said Tsai, who was interviewed Friday at the CLA's headquarters in Taipei, although an attorney at the Legal Aid Society could not say how this would prevent the broker from listing false loans in the document.

But some proposed measures would not favor migrant workers. The CLA has announced its intention to abolish the monthly minimum wage of NT$15,840 (US$483) for foreigner workers. It has also proposed spending NT$500 million (US$15.27 million) to issue integrated-circuit ID cards to foreigners to prevent them from “committing crimes” and “ensuring national security.”

Despite this mixed record, an official at the Manilla Economic and Cultural Office (MECO), which represents the Philippines in Taiwan, expressed optimism for the future.

“(The CLA's) intentions are good,” said Reynaldo Gopez, MECO's labor representative. “But it will take time, as is the case with all bureaucracies.”

And he believes the government will eventually pass the proposed Household Services Act, which would provide protections for local and foreign maids similar to those in the Labor Standards Law.

This will be too late to help people like Mary, who has six months remaining in her contract. Of the 43 Filipina maids who live in her part of Taipei's Xinyi District, only four have one day off per week. More than 23 never have a day off, 12 get one day off a month and four get two.

Of these, one works for a famous singer, another for a diplomat who represents a wealthy Asian country. A third regularly cleans six houses. A fourth, who works for a member of the Legislative Yuan, is illegally employed in the woman's office.

Dogs, children and the elderly are their “passports” to the outside world. “My situation is so hard,” Mary said. “I can only go outside if I take the grandmother with me.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she