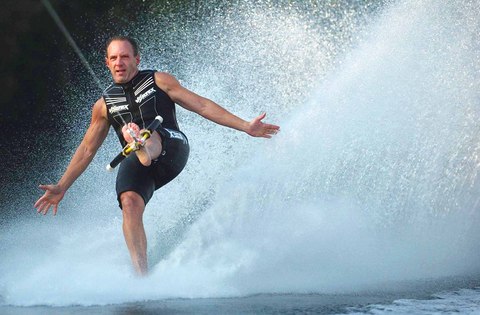

Most water skiers skim along on molded urethane, fiberglass and aluminum. Barefoot water skiers ride on their own naked soles. “The thrill is that you're on your own feet and you're going 64kph,” said Brian Heeney, a member of the Rocky Mountain Barefoot Club in Helena, Montana, and a nationally ranked barefooter since 1991. “It's not you and a million [US] dollars of research and development spent on water skis. It's just what Mother Nature gave you. Hold on to the rope and let's go.”

The origins of barefooting are traced to Florida in the 1940s, and for decades barefooters had to teach themselves, relying on vague instructions and patient boat drivers during countless tumbles. Now barefooting is taught in water skiing schools and recognized by USA Water Ski, the national governing body of water skiing. It has its own competitive circuit.

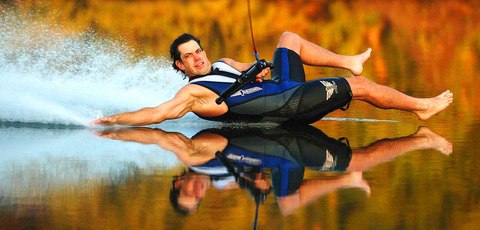

Barefooters typically lie in the water holding a tow rope and, as the boat speeds up, fold themselves in half and get to their feet, with heels dug into the water, toes out in the breeze and the water line at their insteps. Maintaining balance is a challenge. Toes dipping below the water line induce a crash so common that barefooters call it a “toes-to-nose.”

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

“People with collapsed arches have an advantage,” Heeney said. “High insteps, that's a handicap.”

A tournament called Footstock draws about 150 skiers and 2,000 spectators to Peshtigo Lake in Crandon, Wisconsin, every August for a weekend of barbecues, fish fries, camping and figure-eight-style barefooting. In this version of the sport, two skiers go head to head behind one boat, tracing overlapping figure eights and trying to stay upright despite unforgiving boat wakes and turbo speed. Nasty spills are par for the course and part of the fun. “It's like NASCAR, but there's a crash on every lap,” Footstock's director, Gary Mueller, said.

The competition is so ferocious that it has been marred by its own kind of scandal. In the past, some skiers were discovered to have used duct tape on their feet, a blatant breach of the naked-feet-only rules.

More exclusive but no less challenging are tournaments run by the American Barefoot Club, the barefooting division of USA Water Ski, where skiers compete in barefoot versions of traditional water skiing's three main events: wake slalom, tricks and jumps. This year's Barefoot Water Ski National Championships will take place Aug. 8 to Aug. 12 in Polk City, Florida, and winners will qualify for the biennial world championships to be held this fall in Adna, Washington, with about 180 skiers from 16 countries expected.

The Washington events will be on Lake Silverado, a 813m-long artificial lake with sides cut specifically to minimize backwash from boats and 1,400 poplar trees planted around the perimeter to cut down on wind. Glassy, calm water is crucial for barefoot leaps, turns and single-foot maneuvers. Doug Jordan, a barefooter and an organizer of the championships, said he and three partners financed construction of the lake after growing weary of driving three or four hours to public waters where conditions weren't always favorable for barefooting.

The latest craze in barefooting is long-distance river races, which began in Austin, Texas, in 1987 when, as a barefooter named Doug Winters tells it, “some guys were just drinking and said, ‘I dare you to ski this far and this fast.”’ In river races, several high-performance boats line up at once with skiers behind them, and relay teams make lightning-quick passes of the tow rope as boats slow down at prescribed spots. The original race, the Austin Dam-to-Dam, still runs annually.

Winters' club, MVS Barefoot, holds the Mississippi River Challenge, in which racers contend with barge traffic, ferry wakes, treacherous wind and floating debris on the cold waters of the Mississippi near Lake St. Louis, Missouri. Barefooters say that for fun and camaraderie, there's nothing like it.

“It's agonizing during the race,” Winters said. “You don't experience the joy until the end. Then everybody walks away saying, ‘That was awesome. I can barely stand up, but that was awesome.”’

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,