With a bright patchwork jacket from Guatemala covering his broad shoulders, the graying lion of Russian letters, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, paced and shouted as he read some of his poems that once shook the world. Between verses he tossed off advice and opinion about life, love and literature. His audience did not fill a theater in Moscow, London or New York, but a classroom of English students at the University of Tulsa, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he has lived with his family for nearly a decade.

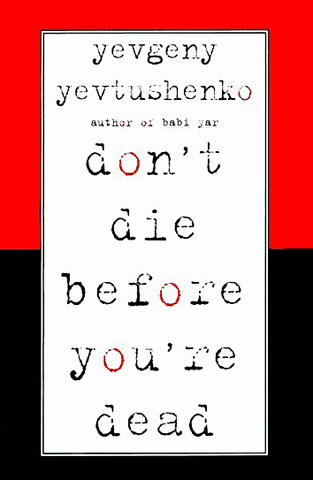

Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko became an international sensation in 1961 when he published Babi Yar, a haunting poem denouncing Nazism and Russian anti-Semitism. Since that time, as a filmmaker, politician and poet, he has been an outspoken activist on a variety of issues, from censorship to ecology.

From 1988 to 1991, the poet served in the first freely elected Parliament of the Soviet Union. "We stopped the war in Afghanistan," Yevtushenko said of that time. "We abolished censorship. We abolished the special commissions that were checking on Russian citizens going abroad. I am very happy that in history my name will be connected to this period."

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Currently, Yevtushenko divides his time between Russia and Oklahoma, where he teaches at the University of Tulsa. "I don't teach literature," he said, "I teach compassion through poetry and film." He has been working on an exhaustive anthology of Russian poetry from the 10th century to the present.

I talked to the poet by telephone from his home in Oklahoma. Here are edited excerpts:

Margo Hammond: In the 1960s, a high school teacher of mine said she would give an A to anyone in the class who could say who was the most dangerous man in the Soviet Union. The correct answer was Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Do you think poets are still dangerous?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: Oh, yes. Poets always are dangerous for the bureaucracy. Do you know the main reaction bureaucrats have to writers who represent the conscience of the people? Jealousy. Bureaucrats manipulate people to love them. But artificially made popularity has very short legs. Truth, on the other hand, takes very giant steps. Bureaucrats want to be loved, but they are tortured by the fact that their popularity is very temporary.

Margo Hammond: Do you think artists would make better politicians than bureaucrats?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: I was a member of the Russian Parliament during the wonderful years of [former USSR president Mikhail] Gorbachev's perestroika. It was for me not a quest for power, but rather a sacrifice of my time for our people. We didn't have many good professional politicians -- just marionettes who were working for the Communist Party leaders. Intellectuals have to take moral control of power. This is one of our duties. Controllers of conscience. We mustn't be indiff-erent to politics. Unfortunately, now many young people are indifferent to politics. I think it's very dangerous.

Margo Hammond: Are Russian youth more politicized than US youngsters?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: No, no. Now, we are both the same. Just like American youth, Russians want to be businessmen, they want to make their careers. Very few want to devote their energies to the social and political field. They criticize politics, but they don't do anything to change it. They have a squeamishness to enter the so-called dirty kitchen of politics. But indifference is not neutrality. To be indifferent is to take a position. I don't mean all young people should be profess-ional politicians, but many of them don't even vote.

Margo Hammond: Do you consider yourself a political poet?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: I didn't become popular as a political poet, but as a poet of love. But, as I said, I think intellectuals have a moral responsibility to speak up. [On March 6] I didn't sleep. In Moscow, an old Cuban man was killed. He was a cigar roller. He was killed by some teenagers, some skinheads, nationalists. I was so ashamed. My poem -- Death of a Cigar Roller -- was published earlier this month in Russia in Novye Izvestiya. I also called a radio station in Moscow and recited this poem to hundreds of thousands of Russians. I hate any kind of aggressive nationalism. That's why I wrote Babi Yar, many years ago.

Margo Hammond: You first visited the US in 1961 -- when you were the most dangerous man in the USSR. What do you see is the biggest change in this country since that time?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: To be honest, I liked the US more in the 1960s than now. When I came, I had never seen protests before. In America, I saw demonstrations against racism, against war. I saw Martin Luther King, marching together with Dr. Benjamin Spock. I heard a young Joan Baez singing We Shall Overcome. This song has been a secret anthem of my soul. I saw great freedom here. Great compassion. Now when I tell my students about that time, unfortunately, they look at me like I'm talking about the history of another country. In Russia, the same thing is happening: Young people don't know history, not even recent history. They don't read books. We shouldn't be indifferent to this. The US and Russia, mighty nuclear states, are responsible for the spiritual life of our people.

Margo Hammond: How close are you to finishing your three-volume anthology, Ten Centuries of Russian Poetry?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: I am trying to finish it this year. I sleep now four hours a day. Each Friday, I publish one chapter from this anthology in Novye Izvestiya.

Margo Hammond: What has been the most difficult part of this project?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: Time. I choose poets and then I have to read everything that poet wrote. It's like rehabilitating people who were behind the bars of oblivion. I pull them out and resurrect them. It's a great responsibility.

Margo Hammond: When you published your first poems in 1949, you were a soccer player. Do you ever regret that you chose poetry over soccer?

Yevgeny Yevtushenko: I may have lost my chance to become a professional soccer player, but my novel, s, is partly dedicated to soccer. The main hero is a soccer player.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by