Tattered book covers salvaged from the Iraqi Academy of Fine Arts and wax sketches of US bombs blowing up Baghdad are part of a rare exhibition of Iraqi artists in New York's SoHo gallery district.

Ashes to Art: The Iraqi Phoenix will be on display at the Pomegranate Gallery from today through Feb. 22.

The exhibit concentrates on subject matter from the most recent chapter of Iraq's history, beginning with the March 2003 bombing of Baghdad.

PHOTOS: AP

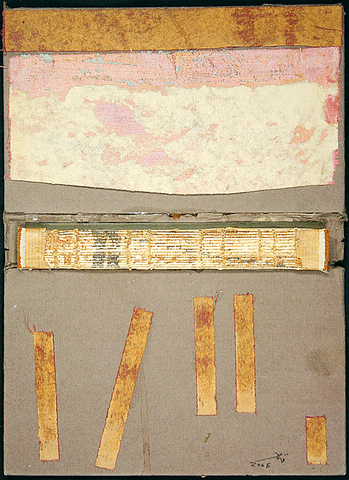

``The morning after that first sleepless night, I went to check on a place most dear to me, the Academy of Fine Arts,'' artist Qasim Sabti, who graduated from the academy in 1980, wrote in his statement for the exhibit.

He described entering the academy's library, which had been burned. Sabti turned books he refers to as ``survivors'' into collages by exposing and reapplying layers of their delicate bindings which are on show in the exhibit.

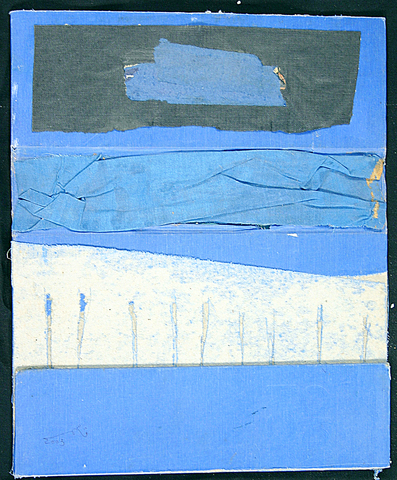

Hana Malallah, the lone woman among the 10 artists represented in the exhibit, submitted the painting The Looting of the Museum of Art, which she created on wood that she cut, burned and painted.

The exhibit's curator, Peter Hastings Falk, points out that a charred element exists in nearly all works in the exhibition. ``This is the aesthetic of the country,'' he said.

The idea for the exhibit began when Falk, whose expertise is in American art, became intrigued with artist Esam Pasha after reading about the artist in an August 2003 article, shortly after the US invasion of Iraq. ``He was painting over a mural of Saddam,'' Falk said.

Falk contacted the 29-year-old by e-mail and told him about his idea of organizing a show of Iraqi artists.

Pasha, a grandson of former Iraqi prime minister Nuri al-Said who was deposed and murdered in 1958, worked as a translator and language teacher, in addition to being a part of the Baghdad art scene. He helped Falk find an ethnically diverse group of Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish artists for the exhibit.

Artists in Iraq have long worked underground. Under Saddam's rule, artistic work was subject to official review. Regulations were relaxed in the 1990s, when officials were preoccupied by international sanctions, but the government began to tax the galleries. Some galleries went out of business while others just went underground.

``Art was growing its roots underneath the soil,'' Pasha said.

Sabti, the artist who salvaged books from the Academy of Fine Arts, founded the Hewar (Dialogue) Art Gallery in Baghdad in 1992, one of a few that would endure the renewed attention of Saddam. Sabti also serves as vice-president of the Iraqi Plastic Artists Society, an organization of artists with 1,780 members.

However, Iraqi artists couldn't show their work internationally without government approval, said Nada Shabout, an assistant pro-fessor specializing in contemporary Iraqi art at the University of North Texas. Uncensored work could only be found in places like Europe, where many exiled artists fled.

``The government had a strong monopoly over art,'' Shabout said in a phone interview.

Pasha recalled a time during Saddam's rule that he showed a friend a drawing he had done of an eagle falling. The friend suggested hiding the piece because the plummeting eagle ``might be interpreted as a symbol of the republic,'' he explained.

Pasha, a self-taught artist who perfected his English by watching American movies, had sold his art to UN aid workers during the 1990s embargo for around US$200 for a piece. In New York, one rendering in melted wax of the bombing of Baghdad is currently listed for US$2,400 on Falk's Web site.

Shabout, the art professor, curated an October exhibit of Iraqi contemporary art in Texas. She found visitors most surprised to find modern art existed in Iraq, and she partially blames the lack of exposure on regional stereotypes.

``It's easier to think of Iraq as the cradle of civilization,'' Shabout said.

Pasha plans to return to Baghdad eventually, and says he is optimistic about the outcome of the war. But when asked about the recent violence, including a suicide bombing that killed more than 130 people, Pasha pauses and strokes his beard. ``It does not look promising,'' he said.

On the Net:

Curator's site: www.falkart.com

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

President William Lai’s (賴清德) March 13 national security speech marked a turning point. He signaled that the government was finally getting serious about a whole-of-society approach to defending the nation. The presidential office summarized his speech succinctly: “President Lai introduced 17 major strategies to respond to five major national security and united front threats Taiwan now faces: China’s threat to national sovereignty, its threats from infiltration and espionage activities targeting Taiwan’s military, its threats aimed at obscuring the national identity of the people of Taiwan, its threats from united front infiltration into Taiwanese society through cross-strait exchanges, and its threats from

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at