Sudoku are deceptively simple-looking puzzles that require no math, spelling or language skills. Unlike crosswords, they don't require an extensive knowledge of trivia. They're logic, pure and simple.

They're also addictive. Sudoku books -- pages and pages of grids with nothing more than numbers in boxes -- are selling so well that they're quickly filling lists of best sellers.

``I can't think of a puzzle book that has sold like this,'' said Ethan Friedman, who edits The New York Timescrossword puzzle books for St. Martin's/Griffin Press, including two volumes of sudoku with introductions by Times crossword guru Will Shortz.

``This is a publishing phenomenon,'' said Friedman. In all, nine sudoku books are planned.

Nielsen BookScan, which lists 10 sudoku titles, estimates that they sold a combined 40,000 copies in the US in just week, the same week that JK Rowling's Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince and Kevin Trudeau's Natural Cures They Don't Want You to Know About were released.

``I'm not surprised that people like the puzzle -- I thought that was almost certain,'' said Wayne Gould, a retired judge from New Zealand who wrote a computer program that has helped popularize the puzzles. ``I am surprised at how people have gotten into a frenzy about it.''

In sudoku, the game is laid out in adjoining grids. Players must figure out which numbers to put in nine rows of nine boxes so that the numbers one through nine appear just once in each column, row and three-by-three square.

The phenomenon originated in 1979, when one of the grids, titled ``number place,'' was published in an American puzzle magazine, according to Shortz, who was curious enough to research its history. The puzzle did not catch on in the US then, but puzzle enthusiasts in Japan loved the idea. By the early 1980s, the puzzles -- renamed sudoku, which means ``single number'' -- filled the pages of Japanese magazines.

Enter Gould, a 60-year-old puzzle enthusiast who in 1997 found himself ``killing time'' in a Japanese bookstore.

``I don't read or write or speak Japanese so there wasn't much that I recognized,'' he said from his vacation home in Phuket, Thailand. ``I picked up a sudoku book and bought it.''

He was soon hooked.

``I'd say, `When I finish this puzzle, I must go mow the lawn.' Then I would finish the puzzle and go on to another one,'' he said. ``I started thinking, `What happens when I solve all these puzzles?' ... I thought I'd write a computer program so that I'd never run out of puzzles for the rest of my life.''

Gould, who had taken up computer programming as a hobby, wrote software that randomly generates the logic puzzles. The grids have only some of the numbers filled in -- players must do the rest.

He also wanted to share sudoku with the world -- and perhaps ``make a bit of money.'' So one day last November, he marched into The Times in London without an appointment, carrying a copy of that day's newspaper with a square cut out and a sudoku puzzle in its place.

Once Gould persuaded the features editor to come down to the lobby, getting him to publish the puzzles was easy -- he offered to provide them daily for free as long as the paper printed the address of his Web site, where for US$14.95 he sells the software needed to generate a lifetime of sudoku -- ``endless puzzles made up on the spot, all fresh and original.''

The Brits went bonkers. Other newspapers quickly realized that they, too, had to provide sudoku to stay competitive.

And that computer program is about to make him a millionaire, says Gould, who now provides free puzzles to 120 newspapers in 36 countries. Other syndicates provide their own sudoku -- Kansas City-based Universal Press and others supply dozens of US newspapers with a daily dose.

The Los Angeles Times started running the puzzles in June. The response was immediate, says Sherry Stern, deputy features editor. ``It's just something that's captured people,'' she said. ``I can't explain it.''

American book publishers saw what was happening in England earlier this year and sensed a big business opportunity.

``There were books on the best seller list there. That was unheard of, to have a puzzle book up on the best seller list,'' said John Mark Boling, a spokesman for Woodstock, New York-based Overlook Press, which quickly obtained the rights to publish some British sudoku books in the US. ``We beat everyone to the punch, basically.''

In July, the first printing of The Book of Sudoku, by Michael Mepham, sold out in two weeks. Three more sudoku books quickly followed, selling a combined 400,000 copies, Boling said.

The Book of Sudoku is also one of two sudoku books on Publishers Weekly's list, at numbers 14 and 15, respectively.

``Our orders go up hourly,'' Boling said. ``We've really been at a rush to keep up with the demand.''

At least three more US publishers quickly put out their own sudoku books.

``This is a major league best seller,'' said St. Martin's Friedman.

New York-based Barnes and Noble, the nation's largest bookseller, bought 28,000 sudoku books from Newmarket Press, according to company president Esther Margolis.

``It could flame out but based on everything I've been able to discern so far, sudoku is a keeper,'' Margolis said. ``It's the kind of puzzle that seems to be so intriguing and satisfies such a wide age range.''

Shortz, who has been addicted to sudoku since April, says their appeal is simple.

``Most problems we face in everyday life don't have perfect solutions. It's satisfying to take a problem through to the end all by yourself,'' he said.

The instructions are short, just one sentence, which Shortz said is ``very rare in puzzles.''

``It's a tremendous amount of payoff for just the tiny work of understanding what's going on,'' he said. It's also the perfect size, always nine squares by nine squares. ``It's small, but it packs a lot of puzzle in there.''

Shortz -- and Gould -- believe sudoku is here to stay.

``It will fade but I don't expect it to disappear for good,'' Gould said. ``I think the crossword and the sudoku will sit side by side for years to come. The crossword is there for the wordsmith and the sudoku is there for the rest of us.''

Today on p17 we begin publication of our own sudoku puzzles, for your enjoyment seven days a week.

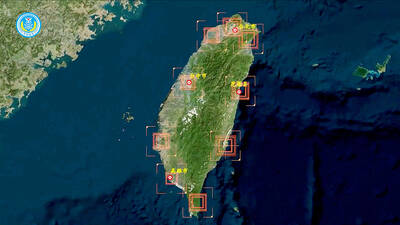

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On